William Castellana’s Personal Project Evolved into a Children’s Book

Photography William Castellana tells a children's story through still life photography,

• July 2020 issue

William Castellana’s latest photographic collection could be considered something of a self-portrait. “Inquisitive Creatures” was born out of his longtime partner’s flight of fancy and propelled Castellana into yet another facet of photography: still-life images of incredibly detailed miniature sets. What resulted is a children’s book about four science-minded critters on a quest to build a time machine—a whimsical tale that, in the aggregate of its characters and the details of the sets, mirrors the creators themselves.

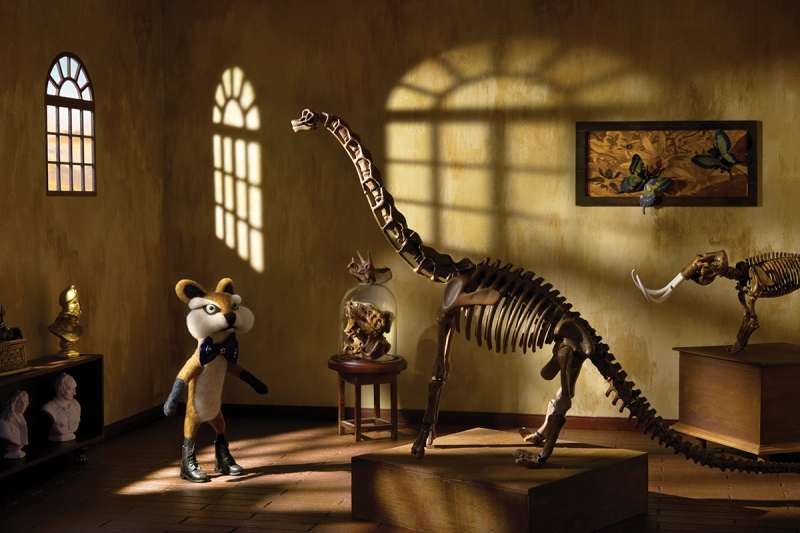

Winston, Alfred, Dempsey, and Harvey are the book’s titular inquisitive creatures, three young foxes and a dog, respectively. They’re students in the steampunk-style Academy of Science presided over by their rabbit professor. Almost every tiny scene is a packrat’s paradise filled with books and beakers, manuscripts and maps, artwork and artifacts, gears and goggles, bulbs and busts, jars and electric jolts. The inquisitive creatures play chess, ponder fossils, practice their musical instruments, and paint the “Mona Lisa.” For young pups, they’re studiously clever and devotedly ambitious. Supplementing the clutter, gadgetry, and furnishings is the light pouring through windows or emanating from candles casting shadows on the walls.

Wee world

Castellana and his partner of 20 years, character designer and prop stylist Linda Montanez, built this world on 4-square-foot sets, everything represented on 1/16th scale, including the characters, floors, windows, furniture, books, pencils, and more.

It’s an entirely new world for Castellana, but his career has forayed into strange lands in the past. His still life portfolio, in addition to commercial and advertising work, includes burning matches posing as stick-figure people, eggs in abstract black-and-white settings, and ice cubes melting into dramatic conceptual sculptures. The former Brooklyn, New York, resident jumped from still life to street life with a series of photographs he made of his Hasidic neighbors. Castellana’s works have been exhibited in museums across the continent and in numerous commercial and art magazines and books.

“I get bored quickly, and I like starting a project that’s out of my comfort zone all the time,” he says. “I like change. I’ve jumped from commercial photography to classic black-and-white still life to 20th-century-style street photography to the ‘Inquisitive Creatures.’ When I start a project, I go all in, but when it’s done, I let the experiences of life whisper what’s next.”

While majoring in philosophy at State University of New York at Purchase College, Castellana happened upon a book of still life photographs by Josef Sudek. “It just grabbed me,” he says. He bought a camera, took a few photo classes, transferred to the college’s visual arts department, and “never looked back.” He also took a woodshop class at Purchase, a skill that proved handy when life whispered “Inquisitive Creatures.”

“Inquisitive Creatures” began with Montanez, who has a background in graphic design. She started collecting vinyl art toys and was inspired to create her own characters. She discovered the hobby of felting, a process of separating wool or yarn fibers and reconstituting them into felt figures. Many YouTube tutorials and “a dozen failed characters” later, she came up with Winston, Alfred, Dempsey, and Harvey. “After making different species of animals, the foxes and dogs were what I ultimately fell in love with,” she says. “I imagined them to be mavericks living in Great Britain during the Industrial Revolution, when things started to become mechanized. I really love steampunk art, and I wanted to infuse that aesthetic in some of the handmade gadgets.”

When Montanez created the scientific theater set for the project, Castellana urged her to think in terms of scale, texture, color, and to emphasize details—things that would translate photographically. “I usually start off by arranging things loosely,” Montanez says, “and then he’ll start moving everything around based on where he wants to place the camera and lights. I learned a bit about photography by watching him, and he pushed me to make the sets more detailed through the use of props. It’s pretty much like decorating a room.” They worked together on “Inquisitive Creatures” in her New Jersey studio for more than two years while both juggled other work and projects.

Although Castellana was working with props for the first time, his biggest challenge was lighting. He used light painting, with exposures ranging four to 10 seconds, creating the combination of natural window light and indoor source light with flashlights, LEDs, and candlelight. Light passing through window frames built into the set creates sunlight shadows on the walls, and a shadow of a clock visible on the creatures’ laboratory floor comes from a window shaped as a clock face.

Castellana had as many as five flashlights on a set and two in his hand. “One can buy expensive continuous lights that have greater color consistency over a dimmable range, but I needed a very precise, pinpoint light source that I could move around freely and custom fit with an aperture-like apparatus.” In post-production he matched the color temperatures of competing light sources and mini-flashlight dimmers depending on what was individually illuminated on each set. Exacerbating his post-production efforts was the color inconsistency of the LEDs that could not be corrected using standard color-correction filters.

Nevertheless, the most labor-intensive aspect of post-production was retouching the characters’ fur, he says. “In some photos, all the characters are present, and I’d often dread cleaning up all the imperfections.” He set his aperture at F8 or F11, which provided the depth of field needed to give clarity to the sets’ detailed props, softening the backgrounds on a couple of images to highlight the focus on a character. “If the background elements were too sharp or soft, we would just move the set back or forward, including the props, in relation to the characters,” Castellana says. “This was easy to do since the walls were not permanently attached to the floor.”

The details in the sets are integral to the story. Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” hangs above the fireplace as Winston reads da Vinci’s Codex Leicester, and Dempsey reads a book upside down looking for clues, a la da Vinci writing manuscripts backward. The scientific theater includes a nod to Nikola Tesla’s coil. Behind Harvey in his chemistry lab is a painting of Isaac Newton, an alchemist as well as a scientist. Harvey has spilled some green goo, which turns out to be the fuel for the time machine. The sets have personal touches, too. Castellana is a big fan of J.M.W. Turner, and the English painter’s “Fishermen at Sea” adorns the wall behind Harvey and Dempsey as they examine clock mechanisms.

Telling narrative

The idea of turning the project into a children’s book emerged once Castellana started photographing the tableaux. They storyboarded sequences, and Castellana wrote the story. “The whole process was flexible, enabling us to tweak things along the way,” he says. They have potential publishers lined up, but the images embody such personality and enigmatic details in arresting compositions that they also stand alone as fine art. The Mulvane Art Museum in Topeka, Kansas, and the Asheville, North Carolina, Art Museum recently acquired several images from the book for their permanent collection. Castellana and Montanez also plan to sell limited-edition archival pigment ink prints of the images. But they aren’t selling the props themselves. “We’re keeping everything,” Castellana says. “We want to use these props for future photographs and stop-motion animations. And besides that, we are just too attached to the miniatures.”

Montanez says the characters are not autobiographical, but collectively, “they do share our passion for hard work and setting goals and seeing things through no matter the outcome.” Plus, the creatures succeed by working together. “So many worthwhile things in life happen by way of collaboration,” Castellana says. “Many projects require teamwork because the outcome would be better than a solo effort. Science and art and many other fields would be disadvantaged without collaboration.”

The storyline reflects Castellana’s long interest in science and art, which, of course, merge into the medium of photography. And he fits the description of Winston, who loves solving problems, harnessing the idea of “special relativity” as the secret to building his time machine. And isn’t photography a kind of time machine? “He believed that playing games, like chess, was the surest way to learn new ways to think about old ideas,” says the book’s introduction of Winston. “He called this process his ‘thought experiments.’”Castellana wrote that, and it offers a convenient label for the path his photographic work has taken. His next thought experiment is already underway, a still life series using a projector to create collage-like images with political subtexts. “The way it really works for me is I’m moved by something emotionally, and then a project ensues,” says Castellana, a truly inquisitive creature.

RELATED: A gallery of Castellana's work

Eric Minton is a writer and editor in Washington, D.C.

View Gallery

View Gallery