When he was in sixth grade, Andrew Pinkham had trouble with reading comprehension, so his parents took him for a Johnson O’Connor aptitude test. It revealed his ability to recognize the quality of notes on a keyboard. “I couldn’t tell you what a C or a D chord was, but I could differentiate up to the hundredth percentile whether one was in tune with the other,” Pinkham says. The testers saw a correlation between that and photography, “and they didn’t know why,” Pinkham says. Neither does he, even now. The test inspired him to buy a 12-string guitar, but mostly he just tuned it: “I didn’t play it that much.”

When Pinkham graduated from high school, his mother gave him a camera. Things started to unfold, particularly after he discovered that Ansel Adams previsualized the images he made. “I’m like, Wow!

Somebody can come up with something they can think about and have that translate into a print. That was mindblowing.” What unfolded for Pinkham was a career specializing in pet portraits that look like paintings evoking rural Americana, people portraits that look like whimsical illustrations, and urban landscapes that look like impressionistic noir renderings.

During a two-hour Zoom call exploring his photography career, Pinkham often touches on the synergy of music and photography. He references famous rock guitarists, but he’s more the photographer version of session player Steve Lukather, pursuing his career with a meticulous balance of artistry and common business sense while capable of chart-topping success. That may have been the true finding of the aptitude test: Pinkham’s attention to tonal detail represents the way he thinks; his photography represents who he is.

ACHIEVING THE TONE

He lives in a South Philadelphia row house a mile down Broad Street from the city center but close enough to the Philadelphia Sports Complex that he can see the fireworks signaling a Phillies victory. “I’m incredibly active and walk a lot,” he says, walks that inspire his urban architecture photography. After attending schools in upstate New York and near Boston, Pinkham has lived in Philadelphia’s environs for more than 35 years. “It’s not too huge, and it’s not too small, either. I gravitate toward cities anyway. There’s always somewhere to go and something new to do.” South Philly is both a working-class neighborhood and a chip-on-the-shoulder attitude, and Pinkham appreciates its affordable housing and diverse mix of residents. “Like rocks in a giant bag,” he says. “Whatever roughness they have around the edges, due to their proximity it smooths that out a little bit, and we’re able to see and experience ‘the other’ more than we would in a rural setting.”

Yet, his portraits of pets and people use the rural setting of Chester County west of Philadelphia, which seeped into Pinkham’s conscious growing up there in the 1970s. The suburban tentacles of Philadelphia and Wilmington, Delaware, stretch into Chester County, which also abuts Pennsylvania’s eastern industrial corridor to the north, but the region maintains an idyllically gentrified countryside that rolls west into Amish-centric Lancaster County. Here flourished one of America’s foremost artistic dynasties, the Wyeths, who profiled the region’s landscape, people, and animals in their paintings. Pinkham fondly remembers visits to the Brandy-wine River Museum of Art, popularly known as the Wyeth Museum, in Chadds Ford. “Being around that stuff as a kid was definitely part of the influence,” he says.

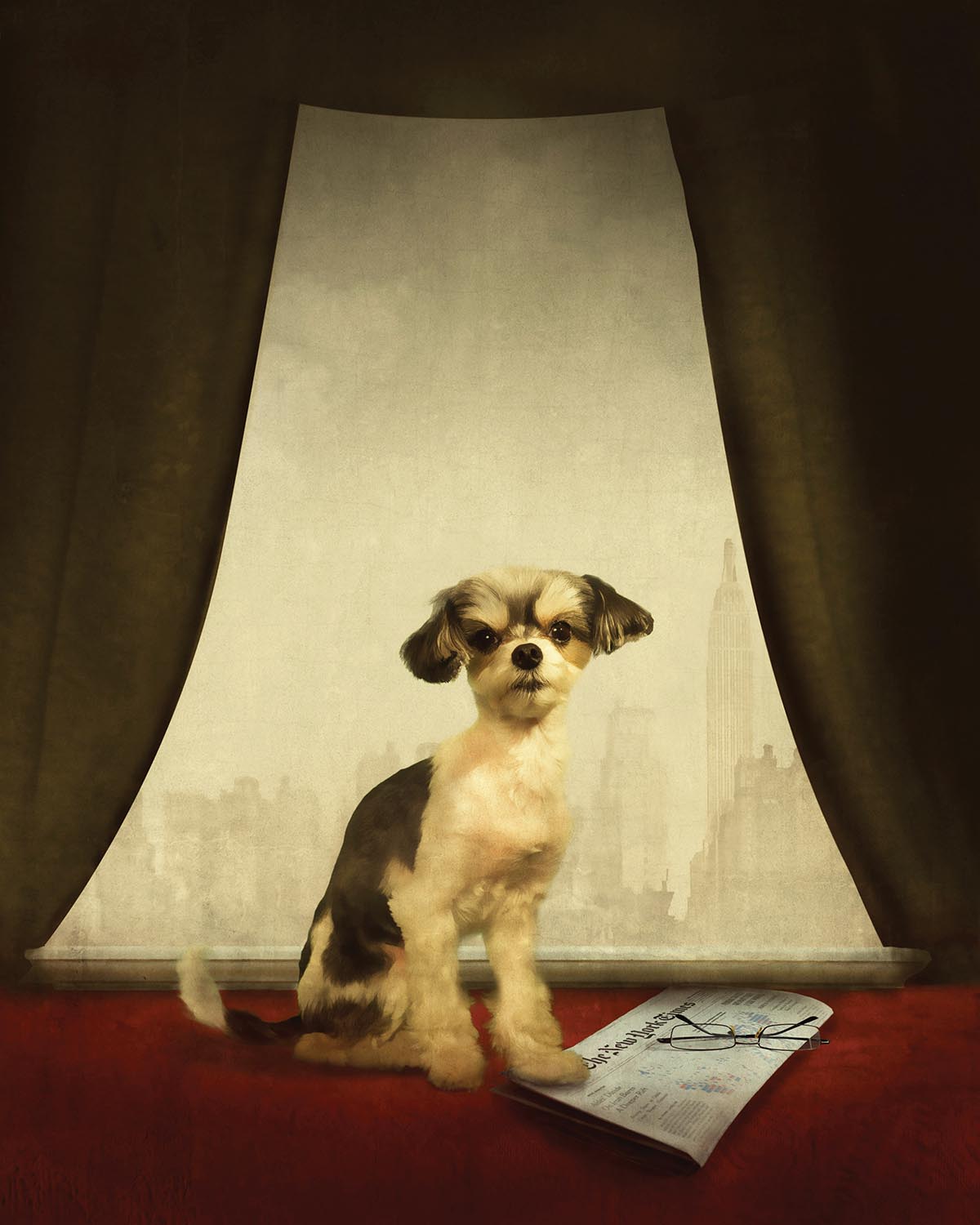

N.C. Wyeth established the family’s artistic heritage in West Chester, but Pinkham is drawn more to the work of a third-generation Wyeth. “I like Jamie’s portraits a lot,” he says. There are similar strains of whimsy and humility in Jamie Wyeth’s paintings and some of Pinkham’s photographs. Though Jamie Wyeth painted portraits of animals, the more direct link to Pinkham is Chester County itself. Pinkham’s dogs, horses, and a giant chicken pose nobly on vast meadows with a distant crop of trees under cloud-dappled skies. For his interior portraits, dogs and cats settle amid the simple décor of landowner nobility, a Dutch Golden Age look.

Such distinguished settings are not merely an aesthetic: They’re a functional tool. “The way I work is backward from what anybody would think,” Pinkham says. “If you called me up and said, ‘Rover is very dear to our family and we’d love to have a portrait of him,’ I’d say, ‘Certainly, we’ll get that done. What would you like the setting to look like?’” Relying on his established style of settings is “the safe route to go because it’s very predictable in its tonality and composition.” Even before the session, Pinkham creates a “perfect, bucolic scene. And then you enter the animal.”

How that animal behaves is immaterial. “Sometimes it’s great; they just sit there. Other times it’s a complete circus, and you have to roll with the punches. I’ve waited a couple of hours for a dog to shut its mouth. I have the patience of a saint with your animal, and it’s usually the people who don’t want to waste my time and say, ‘Come on, Fluffy, behave.’” All Pinkham needs is five great shots to achieve the tone he wants. “But there could be one where the tail isn’t doing the right thing, but the head is, and we can assemble that later on. The aspiration is to get that moment where everything’s great.” He uses a ton of Photoshop, he says, but “it’s not meant to hit you over the head.”

IT’S PERSONAL

Achieving his painterly look is a combination of lighting, lens, and Photoshop layering. At first, he used the magic hour of dusk for effective lighting, but that relied too much on weather, calendar, and dogs’ temperament. Determined to move the sessions indoors, Pinkham put six months into study and testing, using his own greyhounds as subjects, to develop light sources replicating magic hour tonality. Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Wyeth paintings use sunlight through windows as their main light source. “The light was directional but soft as well,” he explains. Pinkham came up with a combination of a soft umbrella light and an on-camera flash at 1/28th power: “One light that is very diffused and big and another that is very focused and directional, generally on the mask of the subject’s face—just a kiss of light.” He refines the lighting by adjusting each light’s distance from the subject: “It’s a light mix, you could say. It’s good to have that kind of skill: It really opened up a lot of opportunities. Now I can photograph the dogs all inside and we don’t have to worry about them running away.”

Pinkham comparing tonal quality in photographs (light mix) with that of recordings (sound mix) is one of several music references he sprinkles into the conversation. He diverges into the dynamics of “the visual part of growing up and the musical part,” including an older kid down the street who had a dark room and cameras but also introduced Pinkham to the newest, “blow your head off” rock ’n’ roll records.

What’s important to Pinkham now is “having the sensibility to figure out and articulate why I like something,” musically and visually. “And it’s personal for me.” For example, while he still considers Jeff Beck in a category of one for technical guitar skills, he has a more important category for the likes of Jimmy Page and Keith Richards, masters of “a filthier, nastier guitar sound” better suited to their brand of songs. “If we think of things like tonality, that can be a universal thing. As a photographer, I have a palette I work with. It needs to have a little bit of grit, needs a little bit of lived in. The medium of visual photography is very clean. I have to put some sort of layering over that.”

His source for such layering comes from his bread-and-butter job as staff photographer for the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts. The Philadelphia nonprofit performs conservation work on historical papers and books. Pinkham documents the objects’ conditions before and after restoration, and his images of textured blank pages—some “moldy, old, and beat up”—have become Photoshop layers of various opacity providing the grittiness or old painting timbre he desires in his own images.

Pinkham does pet portraits on commission. “It’s something where very few people have an interest in them, but the people who are interested in them are really interested in them. It’s like finding your tribe.” But it’s not necessarily profitable in the aggregate. When he launched his photography business, Pinkham always worried about the financial side of the enterprise. His four-days-a-week job documenting conservation work allows him the creative bandwidth and time to pursue his artistic endeavors. “I’m able to concentrate on what interests me and not worry about what keeps the lights on,” he says.

What he most wants to avoid is a “Walmartization” of his product. “I figured out early on there wasn’t a shortcut way of doing this. I wasn’t willing to compromise the style and the quality of what I was doing.”

Eric Minton is a writer and editor in Washington, D.C.

View Gallery

View Gallery