In 2018, Johnny Crawford was attending a men’s breakfast at an Atlanta church when some of the men began sharing stories about the Vietnam War. Although he’d known these men for over 10 years, Crawford hadn’t heard these stories. He hadn’t known, for example, that his friend Johnny Miller had been shot in the lungs and injured by a bomb in the war, and once he recovered and relearned how to walk, was unable to get his job back despite suing his employer. Crawford hadn’t known that, due to the draft, fellow church member Byron Powell had lost out on an opportunity for a career as an astronaut and almost lost his life for attempting to wash his clothes in a segregated laundromat.

“These men were among tens of thousands of Black men fighting and dying for the people of South Vietnam to have rights they didn’t enjoy as Americans,” Crawford says. And given that their stories had been unknown to him, he adds, “I knew thousands of men in other communities with similar stories were also unknown."

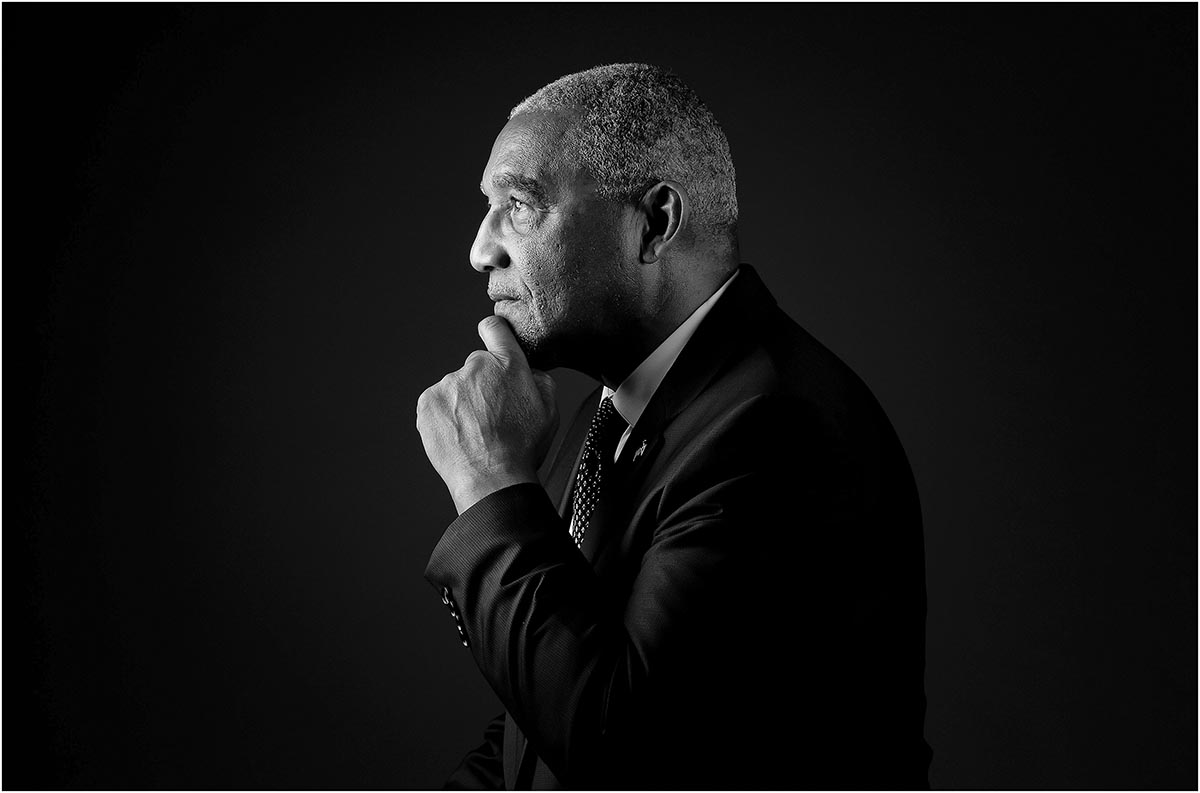

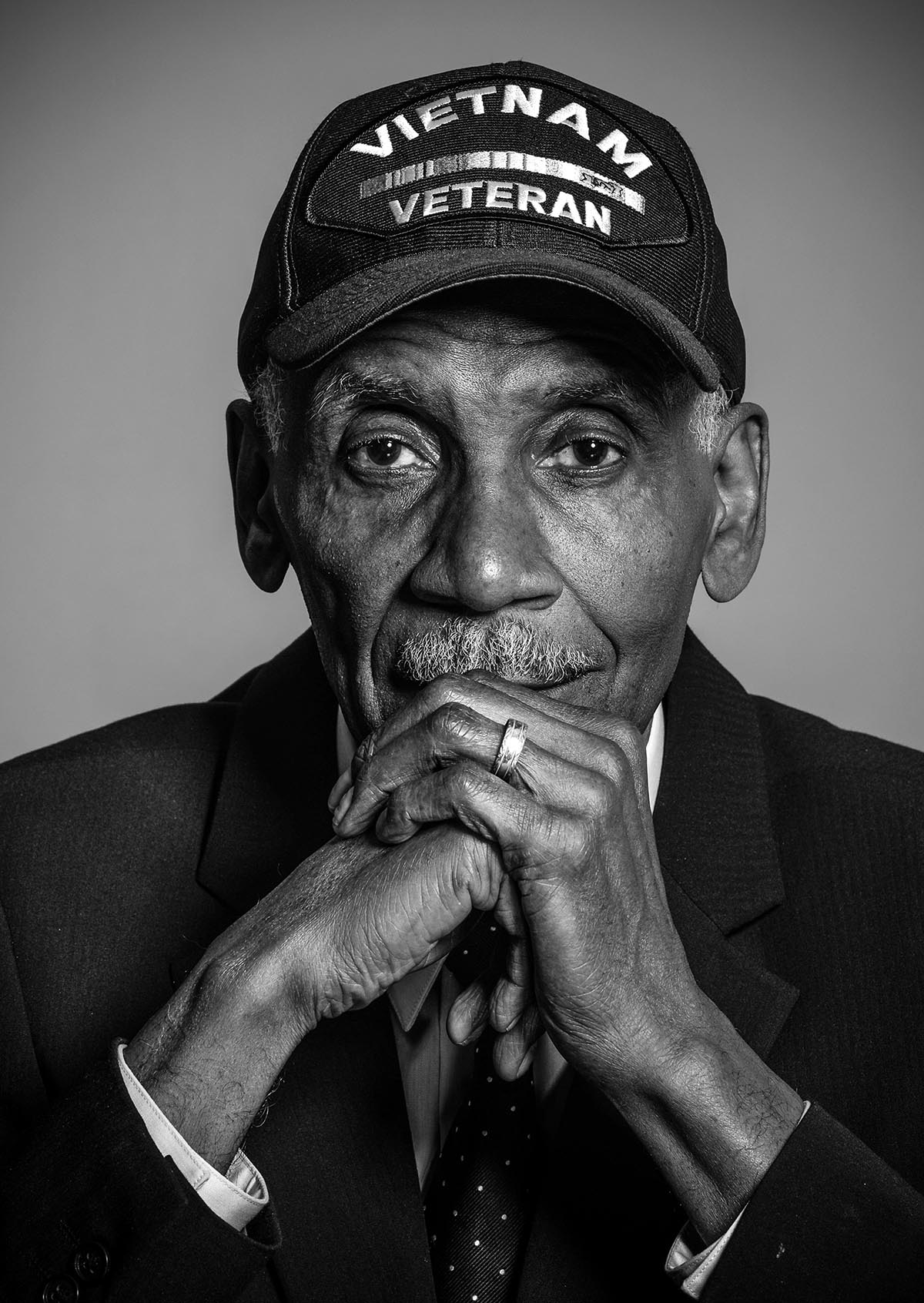

To highlight these stories, Crawford decided to pursue a personal portrait project, “Vietnam Black Soldiers Portrait Project.”

To find portrait subjects, Crawford began with his church contacts, then recruited additional subjects through referrals, veteran’s organizations, and his website. “In the beginning, two out of three veterans declined to participate because of PTSD issues or because they didn’t want to relive their horrific memories,” he says. But over time, Crawford, who has a 28-year background in photojournalism, has made black-and-white portraits of over 100 veterans, photographing them with his Nikon D750 on a gray seamless backdrop with two lights and soft boxes. He shares the photos with his subjects and on the project’s website.

His grand plan is to make portraits of veterans in 19 states and Washington, D.C., and exhibit prints in local museums, churches, and schools. The works have already been exhibited in Georgia, and portrait books are available on the project’s website.

Financing the exhibitions has been a challenge, Crawford admits. “Most of the funds [for the project] have come from my 401(k), one small grant, and a donation from my church,” he says. But it’s not a project driven by profit, he adds. “The project is driven to preserve these men in history.”

Amanda Arnold is a senior editor.