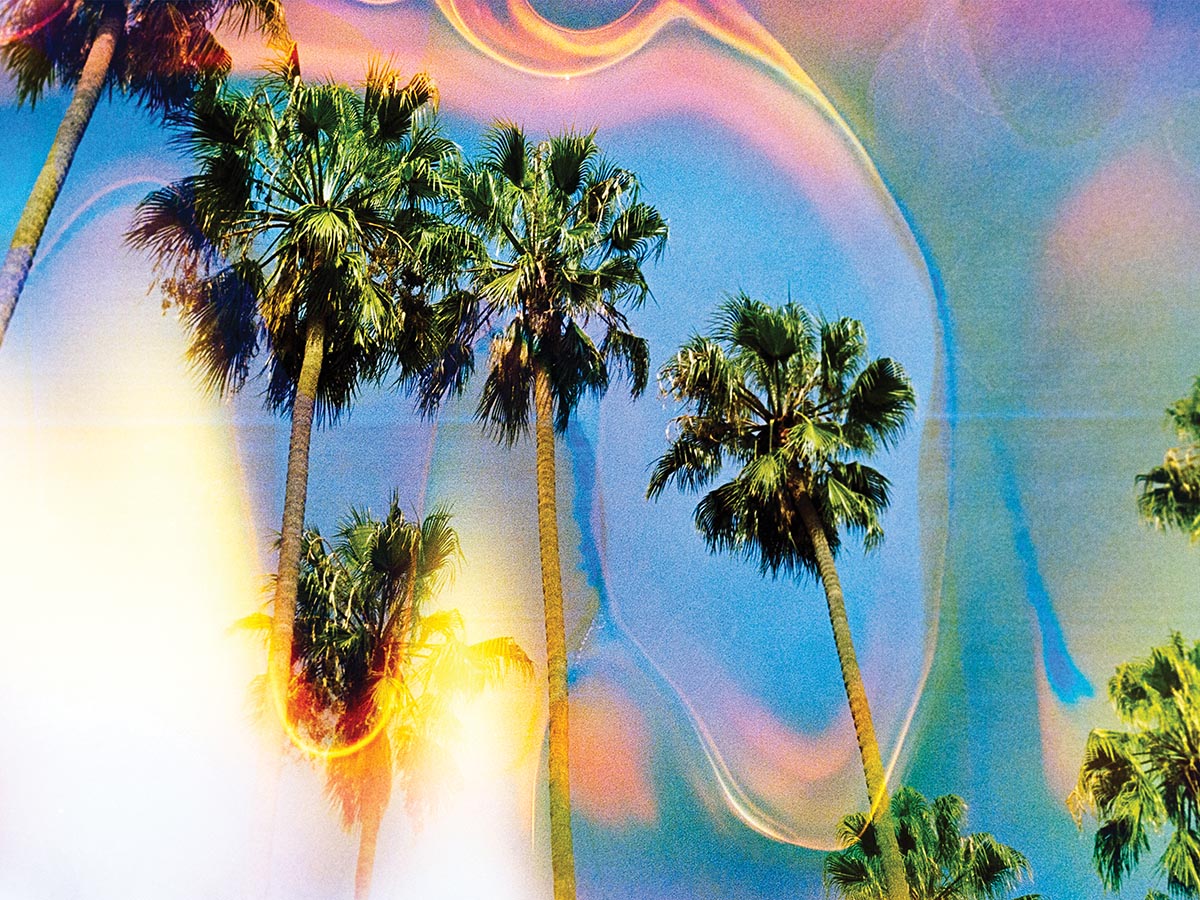

It was “love at first soup” for Atlanta-based fine art photographer Mallory Brooks when she began experimenting with the film soup technique. “My first roll was everything I had hoped it would be, with vibrant color shifts, funky textures, and light leaks,” she says. “I was hooked, and souping has become my favorite thing to do with a roll of film.”

How: She shoots a roll of film, places it in boiling water, and then adds various enhancements—salt, lemon juice, dish soap. “Really, you can use anything,” she says. It’s an experiment. The film soaks for 24 hours and then is left to dry for a few weeks before she develops and scans it.

Why: Besides the vibrant look of the final product, Brooks is enamored by the element of surprise. “Each time what results is pure chance. … Every frame on the negative is different so it’s completely unique and that’s what I love about it. The results can be crazy, but they can also be crazy beautiful.”

Tips: Keep your subjects and compositions simple and leave room for white space, Brooks advises. “The color shifts and textures can overwhelm a busy image.” Also, don’t send souped film to a lab without first checking that they’re receptive since the soup enhancements can taint a lab’s chemicals, which is why she develops her souped film at home.

Risks: Unpredictability abounds. “From the subject matter that’s been photographed to the type of film to the ingredients used in the soup, you don’t know what’s going to happen until you develop the film,” Brooks says. She might find that images have been completely overwhelmed by the soup and are barely or not at all visible. “I have to be at peace with the chance that I’ll get a roll full of many desirable images or only a few to none at all—all these scenarios have happened. But I’m willing to risk these possibilities for creating my art.”

Amanda Arnold is a senior editor.