Power of Suggestion

Collaboration is the heart of Michael Kenna’s minimalist landscapes.

• January 2022 issue

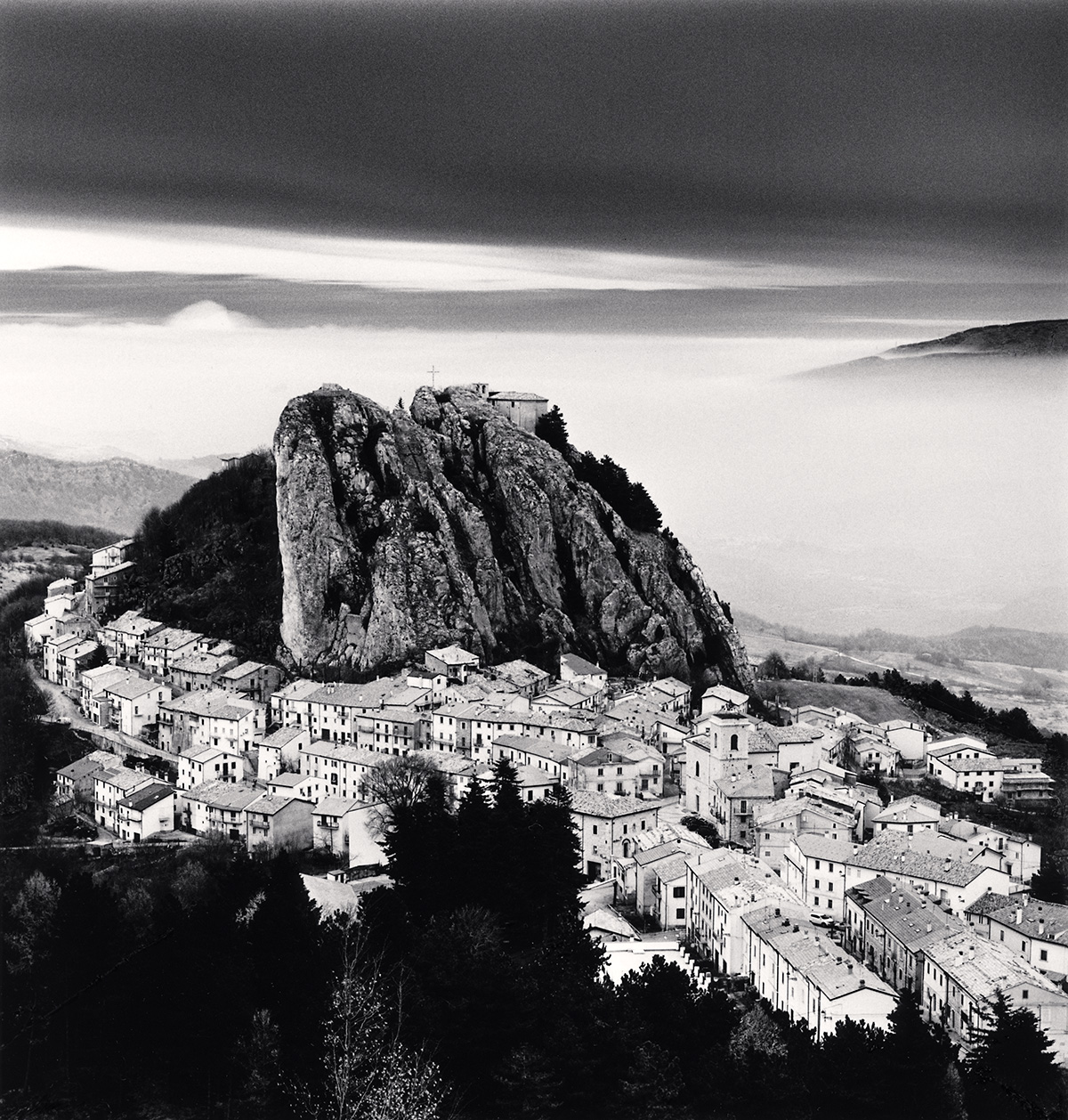

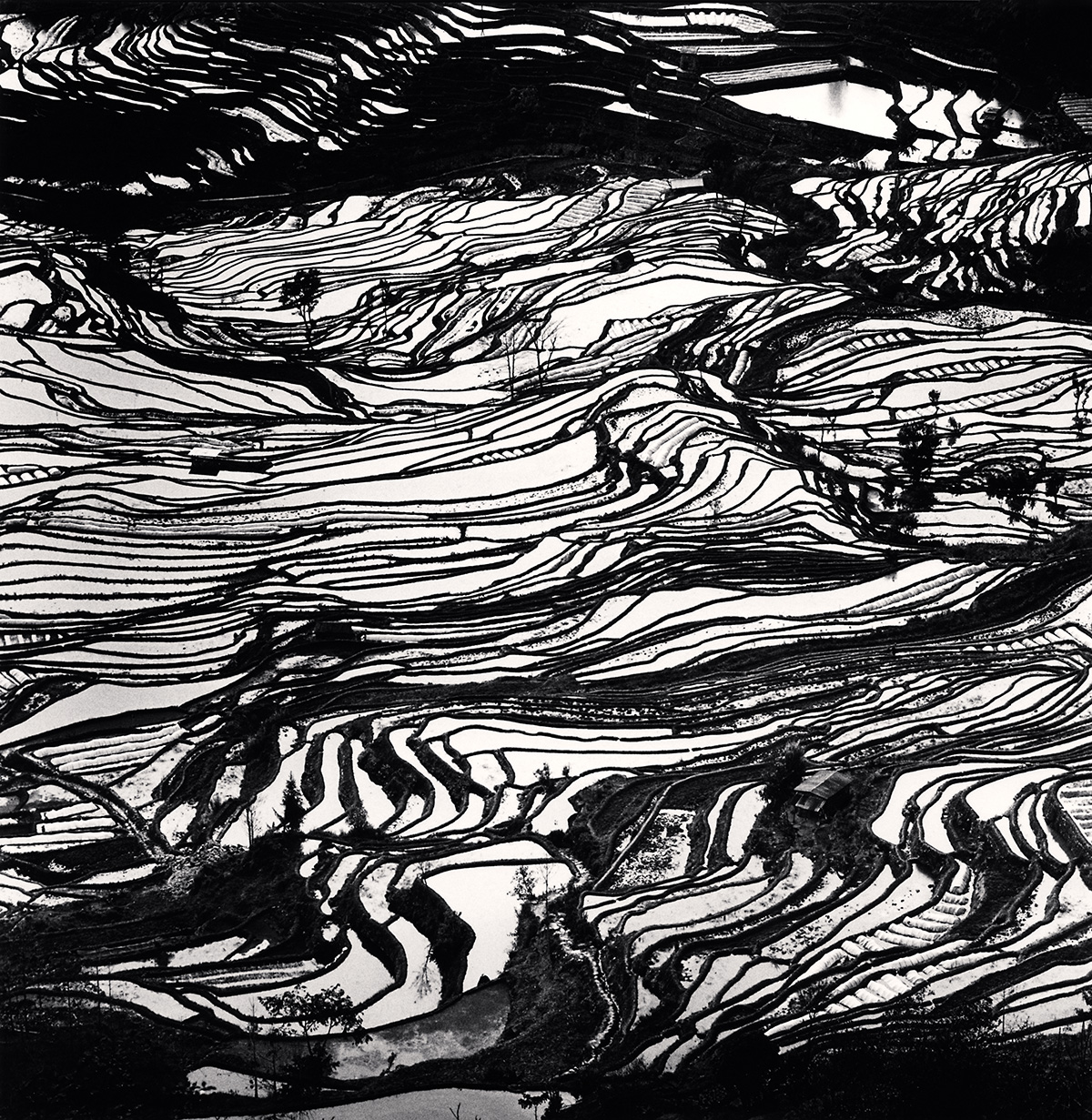

“I look for what I cannot see.” This is one of landscape photographer Michael Kenna’s favorite phrases, and anyone familiar with his minimalist black-and-white fine art photographs can see why. This Zen-like sentence contains a lifetime of learning, seeing, and doing on Kenna’s part, which is reflected in his elegant images.

In his cozy Seattle studio, Kenna smiles broadly when asked to expand on his comment. “Love to,” he says, betraying just a hint of a northern England accent. (He was born near Liverpool in 1953 and has lived in the United States for four decades.)

“I’ve always been more interested in the power of suggestion rather than the literal description of a place or a landscape,” he begins. “In fact, I often think of my work as a sort of visual haiku. It is my attempt to evoke and suggest through as few elements as possible rather than describe with tremendous detail. And I am always looking for those things I cannot see—things that exist through the trees, behind the wall, in the clouds—things that are suggested.”

“Heaven”

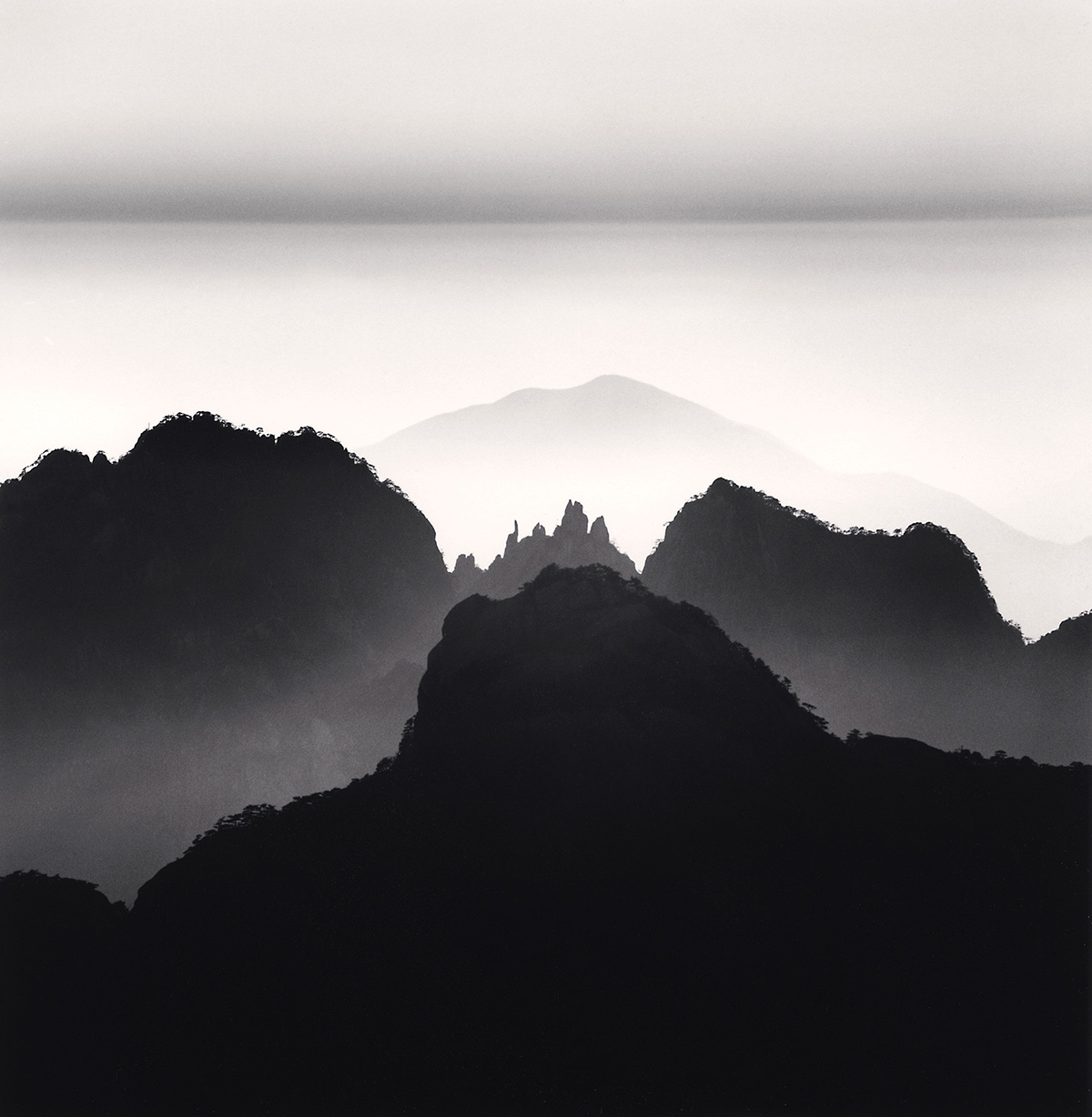

He pauses for a beat and tells a story about “wandering around” the Huangshan (or “Yellow”) Mountains in eastern China in 2008. “It was cloudy and raining and nothing much was happening. But I kept trying to find things. Then this massive, dark gray cloud parted to reveal a miraculous scene. I call the photograph I took ‘Heaven,’ and it’s still one of my favorite images. It embodied, or proved, what I had long yearned, hoped for, and believed in—that what we see is not actually what is there. There is so much more.”

FILM ENTHUSIAST

Kenna’s lifelong quest for more has earned him legions of fans as well as international praise. As one writer noted, Kenna “is an innovator and true master in a field of photography he pioneered himself. ... No wonder his masterfully crafted prints are always sold out, his books are considered works of art, and his exhibitions are always sought after.”

More than 80 published books, catalogs, and monographs chronicle his work. His much-in-demand photographs sell widely and have been shown in more than 490 one-person gallery and museum exhibitions throughout the world. His original prints are in the permanent collections of over 100 museums, including New York’s Museum of Modern Art, London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Shanghai Art Museum. He’s been called “an icon of the photography world.”

Photographer Michael Kenna

After studying photography and printing in England, Kenna came to the United States in 1977 and landed a job as a printer for legendary San Francisco photographer Ruth Bernhard.

“Working for Ruth was a godsend,” says Kenna. I learned so much from her about the gallery structure, how to sell prints, how museums worked, and how one was able to make a living in the fine arts world. She had such great connections and so much knowledge; she was key to my development as a photographer.”

While working for Bernhard, Kenna did some commercial photography and his own personal landscape work. “I was heavily influenced initially by European photographers such as Eugene Atget, Josef Sudek, and England’s Bill Brandt. I liked the way they captured only what was essential to the image. Later I also admired the work of American photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz and Charles Sheeler. I admit that if I have achieved anything, I’ve done it by standing on the shoulders of giants like this.”

Galleries became interested in Kenna’s moody black-and-white landscapes. At the same time, he was landing commercial work with well-paying clients such as Volvo, Rolls-Royce, and British Rail. “I had trained as a commercial photographer in England, but landscape photography was always my true love. But my commercial work gave me a safety net that let me do the personal work I wanted to do. It also helped me discover the world.”

During the 1980s and ’90s, when he had many lucrative commercial assignments, Kenna developed a philosophy about working for clients. “I would always do what they wanted me to do, but also made a point to do what they didn’t know they wanted me to do. And invariably they would choose the shots they hadn’t asked me to do.” He laughs as he recalls an assignment for Volvo where he shot more than 200 rolls of film all over Scotland’s breathtakingly beautiful Isle of Skye. “But the image they chose was one of the first I made, in an empty, misty motel parking lot on the way to Skye! That happened a lot.”

Kenna had always used black-and-white film but his commercial assignments dropped off when digital emerged and clients expected to see instant results. He’s maintained his loyalty to film throughout his career. “I tried to switch to digital but found it too easy,” he admits. “There is something about analog photography that is like playing a musical instrument. You can always fail; it is a very fallible process. With film you never know what you’ve got until it’s processed, and that keeps me searching. There are so many idiosyncrasies to the process that you can have so many surprises. I just love all that stuff— the unexpected, the surprising.”

Using film is like walking down a road, says Kenna. “I don’t get excited about walking along a road where I can see the end point. I like getting lost and taking diversions. I like the long, slow journey of the silver medium. And I like making good mistakes, which I do all the time.”

Kenna is also known for his long-exposure night photography and says he is drawn to it for the same reason he’s drawn to film: “It’s the unpredictability that intrigues me. During a long, multi-hour exposure the world changes and you lose control. Also, I find myself closer to nature when I am doing night photography. I consciously slow down and am more aware of what is going on around me such as the position of the clouds, the phase of the moon, when stars will leave trails on the film and more. At night there is often a sense of drama, a story about to be told, secrets revealed.”

“Winter ... It’s sparse, moody, more atmospheric. For example, with trees you can see their skeleton in winter, not merely the clothes they are wearing the rest of the year. You can see so much more, so much more deeply.”

Michael Kenna

He lists France and Japan at the top on his list of favorite countries in which to photograph. “I’ve photographed more in France than in any other country,” he explains. “It is so rich, so romantic.” He’s done some of his most popular work in Japan, and it’s not surprising that he describes the country as “mysterious” and “wonderfully alluring.” His favorite time of year to photograph? “Winter. Definitely winter,” he admits with a broad smile. “It’s sparse, moody, more atmospheric. For example, with trees you can see their skeleton in winter, not merely the clothes they are wearing the rest of the year. You can see so much more, so much more deeply.”

Over the years, just as he’s remained faithful to analog photography, black-and-white film, and sepia toner, he’s continued to print his work almost exclusively in an 8x8-inch format. “I like the intimacy a smaller print affords,” he says. “With an 8x8 the best viewing distance is about 10 inches away. That helps invite a viewer into my work.”

He recalls experimenting and creating a 3x5-foot print of one of his images, “The Wave,” in 1981 (above). It quickly sold but Kenna admits he had second thoughts about it. “It didn’t have the detail the smaller prints had, and I was never fully happy or satisfied with it,” he remembers. “I realize that when you put your work out into the world it has a life of its own. But eventually I tracked it down, bought it back, and destroyed it,” he confesses.

COLLABORATING WITH NATURE

Kenna’s work rarely features people, although his landscapes are known for their intimacy. In fact, he describes his landscapes as a joint venture: “As a photographer I have always felt I am a collaborative partner. I never felt I was the artiste creating something; rather, I was essentially working with a subject. Whether I am photographing a tree or a mountain, if they didn’t exist, the photograph would not exist. To have this huge ego that I am this great creative artist has just never made any sense to me.”

He continues, “I truly believe we are part of one whole, and whether an object appears animate or inanimate, it is animate and part of the whole. We are connected in some way. So, I have always felt it was responsible of me to ask permission of whatever I am photographing. It’s not like I am going to walk up and say ‘Hello’ to a tree, but I need to make some type of connection. I may go up and touch it. I am never comfortable with the feeling of taking. I feel we are sharing. The tree is sharing this beautiful visage, its animate life, its whole history, and I am recording it, not creating it. It is a collaboration.”

Kenna has compared this relationship to being friends with someone. Just as he returns to visit friends again and again, so he returns to the places he’s photographed. Over the years he’s photographed many of his favorite scenes a number of times to see how they’ve changed and how conditions around them have changed.

“Kussharo Lake Tree”

In the winter of 2002, he spotted an oak tree on the banks of Kussharo Lake in Hokkaido, Japan. “I’ve photographed countless trees, but this one had a special character,” he explains. “It was like an oversized bonsai—elegant and graphically powerful.” Over the next decade or so he returned to make more portraits of it. As he has written, “Between my visits, branches broke and fell, but to my eyes, this aging tree remained graceful and resilient. I began to regard her as a dear friend and greatly looked forward to our reunions.”

Thanks to the many moody photos he made of the oak on these pilgrimages, the tree became known throughout Japan as “Kenna’s Tree.” In 2015 he published a collection of them in the book “Kussharo Lake Tree,” which quickly sold out.

In 2009, the aged tree was cut down for safety reasons. “Time passes and change inevitably happens,” says Kenna. “Friends come and go. It was a privilege to have known her.”

Happily, thanks to Michael Kenna’s astute eye, the tree lives on in black-and-white.

Robert Kiener is a writer in Vermont.

View Gallery

View Gallery