One Thing Leads to Another

Philip Bermingham knows how to create amazing opportunities.

• September 2023 issue

A master networker with a knack for saying just the right thing at just the right moment, Philip Bermingham has forged a 40-year career out of making connections. Though the bread-and-butter of his business has always been family portraits, he’s fueled that work with prominent clients by taking every opportunity to photograph the performing artists, dignitaries, politicians, and other public figures who mix and mingle in the Washington, D.C., area where he resides.

“Get to where your clients are socializing,” he says. “That is the key to it.” If you capitalize on every chance meeting within that realm, you—like Bermingham—will be in awe of where it leads.

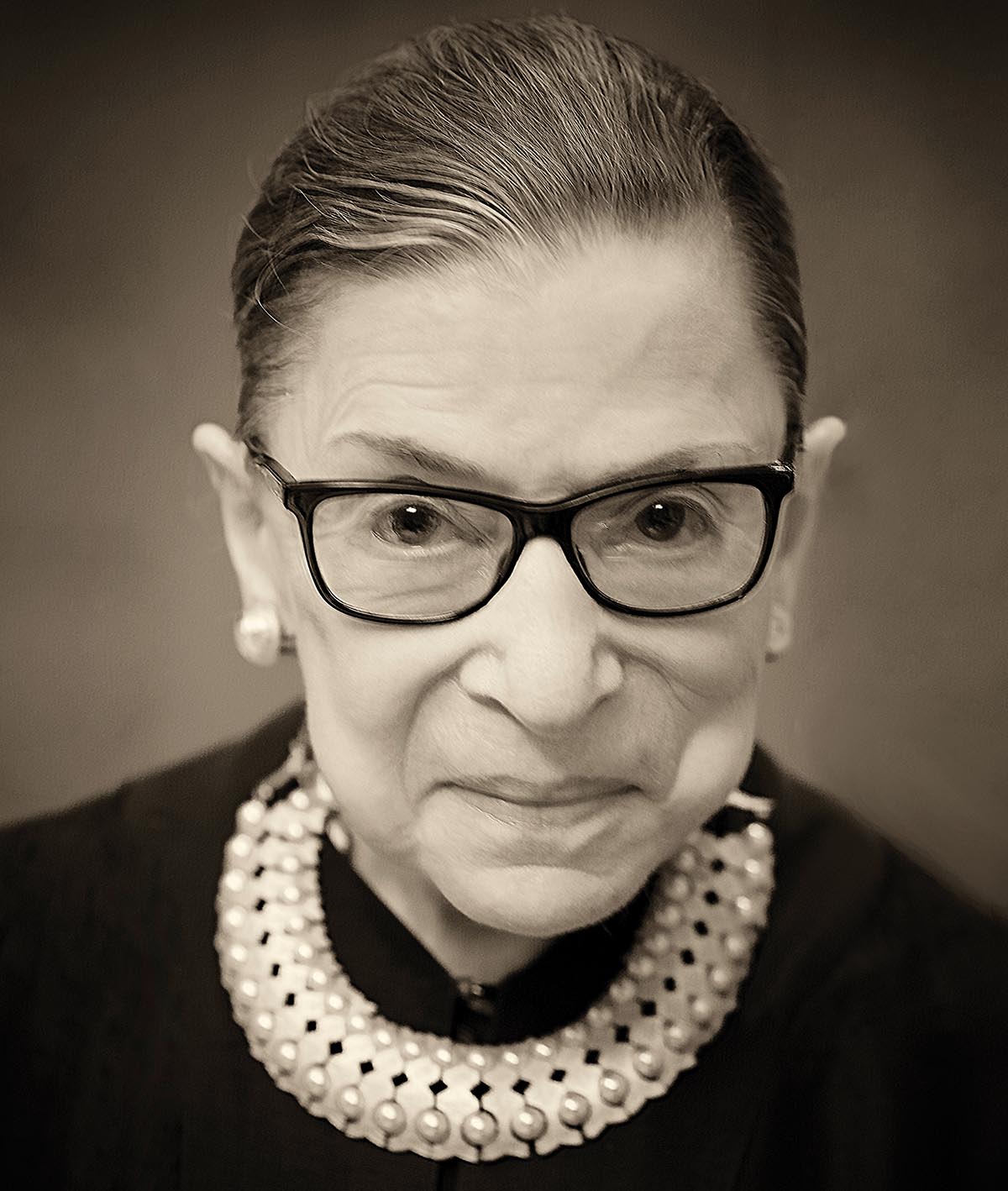

A SUPREME JUSTICE

Bermingham met Marty Ginsburg and Ruth Bader Ginsburg when he applied to purchase a unit at The Watergate in Washington, D.C., where the Ginsburgs lived. As a member of The Watergate’s co-op board, Marty conducted the interview with Bermingham that’s part of the purchasing process. As neighbors, Bermingham often ran into Marty at the Safeway, where they chatted and joked. The Ginsburgs were avid opera fans, as is Bermingham, so they saw each other regularly. This crossing of paths ultimately led to an iconic portrait of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

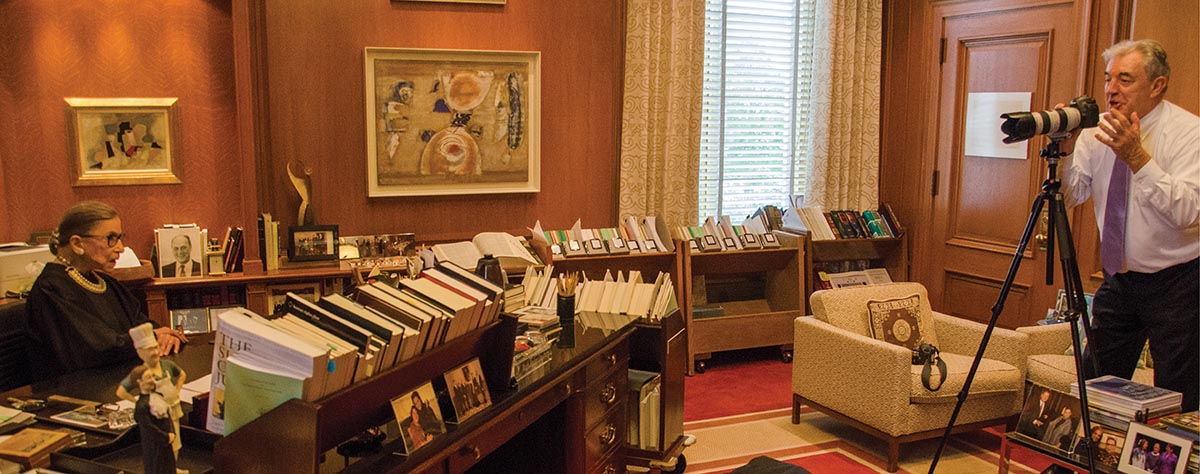

“She was quite lovely,” Bermingham says of her demeanor at the portrait session. He recalls that riding in an Uber on the way to make the portrait, a demonstration snarled local traffic. He and his daughter Scarlett, who he had invited to watch the session, were an hour late. “When I got there I was really concerned,” says Bermingham, but he found Ginsburg to be gracious and relaxed, saying that she understood how unpredictable D.C. traffic could be. She gave Bermingham and his daughter a tour of her chambers and showed her collection of collars, explaining when and why she wore each style. “I don’t understand selfies,” she commented, which amused Bermingham, but she was happy to pose for a photo of the three of them together. “It was a fabulous day,” he says.

When it came to the portraits, something stood out to Bermingham: At her advanced age, Ginsburg held her head at a tilt with her chin pointed downward. To create a photo that appropriately conveyed her power and captured her face looking straight into the lens, he would need to point the camera up toward her face with the ceiling behind her. He got down on the floor to take the shot. “You have to do what you have to do when you’re a portrait photographer,” he says.

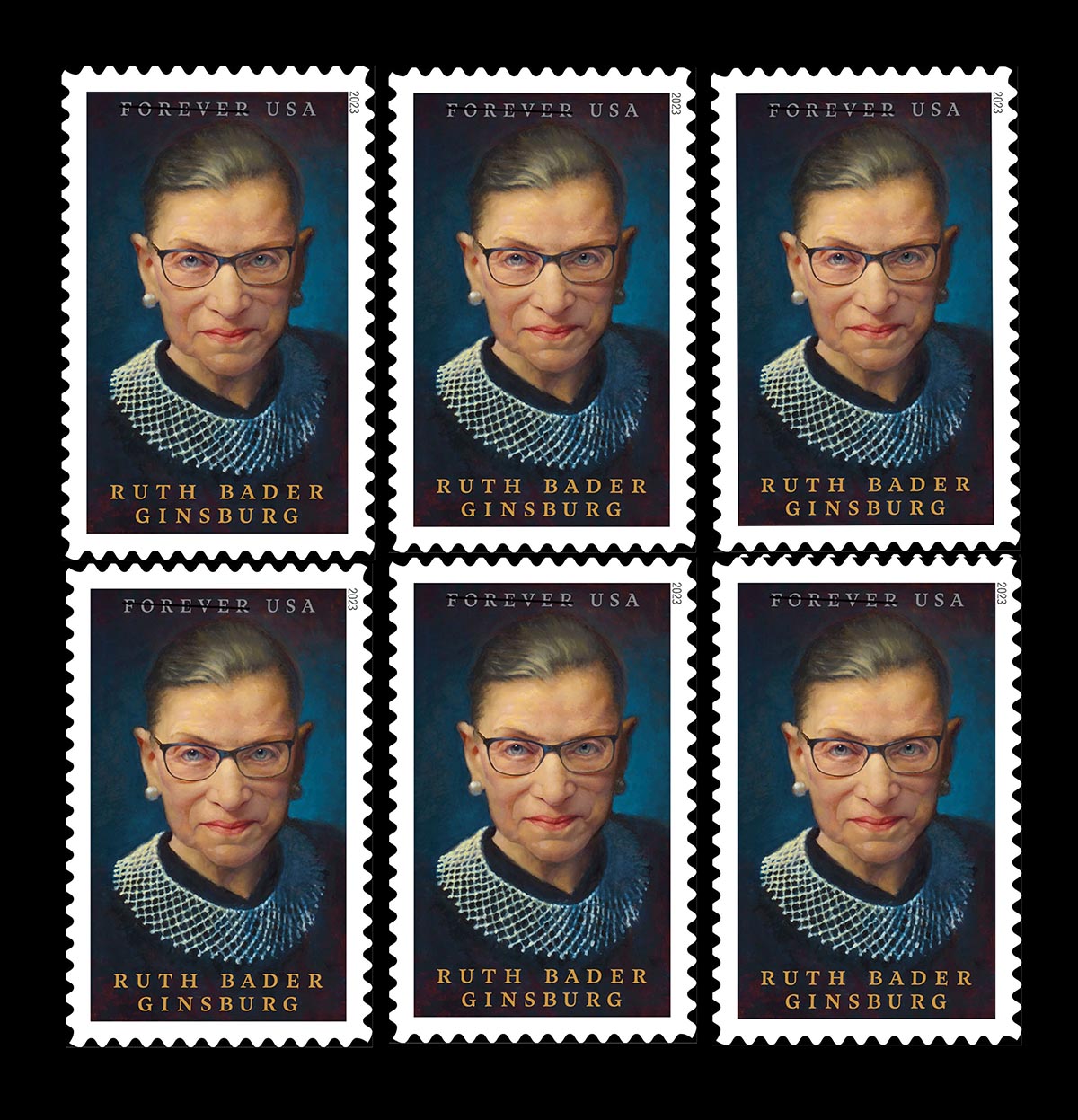

That decision to shoot from below made all the difference, and yet another opportunity arose—to have one of his portraits on a U.S. postage stamp. The United States Postal Service reviewed thousands of photos of Ginsberg before selecting Bermingham’s portrait. The Ruth Bader Ginsberg stamp is set to be released on Oct. 2 while also being unveiled at the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution.

MELODIOUS ARTISTS

When Bermingham was waiting to be interviewed by Marty Ginsburg at The Watergate, there was another gentleman waiting beside him: world-renowned opera singer Plácido Domingo. The two hit it off while they killed time, chatting about Domingo’s new job as artistic director of the Washington National Opera and Bermingham’s photography work.

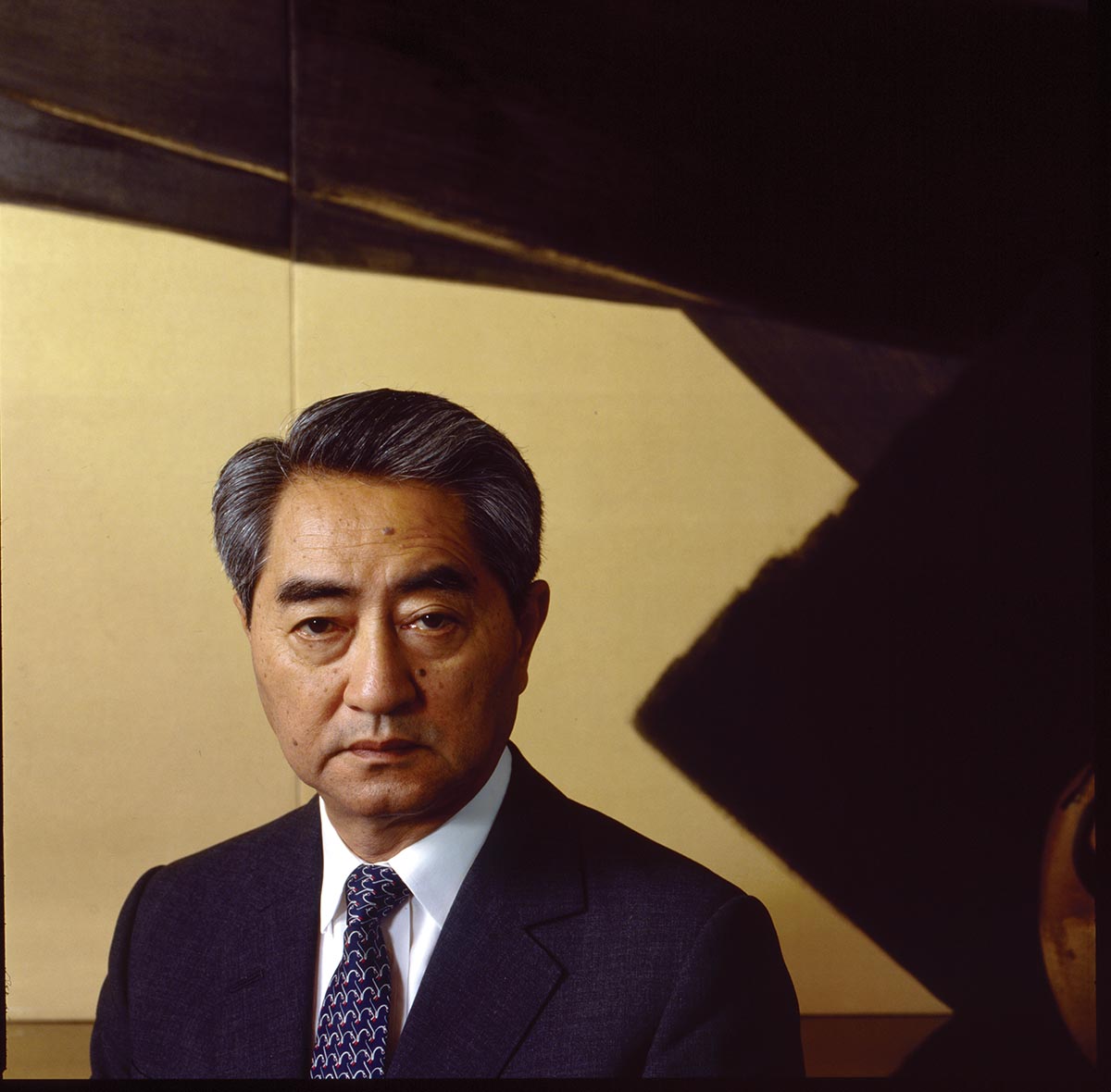

Thanks to that chance meeting—and the fact that Domingo moved onto the same floor of The Watergate as Bermingham—Bermingham eventually photographed more than 500 opera singers over the course of a decade. “They had seven operas a year, and I did that for over 10 years during his tenure,” he says. The assignment included travel to Japan, where the group performed “Otello.” Bermingham’s job was to photograph each performer in costume during dress rehearsals on Monday and have prints on display in the lobby by opening night on Friday. “It was a nightmare getting it ready,” admits Bermingham, but it was important to Domingo that the photos show the performers in full dress with limited retouching.

DIPLOMATIC TRAINING

Bermingham was born in Cheshire, England, and joined the Liverpool Police Cadets at age 16. Eventually he moved to Bermuda, where he worked in the police force’s photography division, which was his introduction to the craft. He moved to the United States in 1978, and set up a photography studio in Washington.

In the late 1970s and into the ’80s, a local magazine called Washington Dossier published an ambassador edition using headshots provided by the embassies. The photos reminded Bermingham of the mugshots he’d seen in the police force, so he reached out to the magazine and offered to make portraits of each ambassador. He would provide the magazine with a black-and-white glossy for each person, and would be allowed to sell images from the sessions to subjects who desired them.

In three months, he photographed 126 of the 131 ambassadors, lugging his equipment up flights of stairs at embassies with no elevators and noting that the ambassador’s office was always on the top floor. “Eventually I realized I could set the light up vertically rather than horizontally so I wouldn’t have to break it down every time I went through a door,” he says. “I became very accomplished at getting in and out very quickly. …. I was basically learning on the job.” The magazine was so pleased with his work that they used him for the next six years to photograph new ambassadors. Meanwhile, he accumulated portrait clients among the diplomat community and beyond. He did engagement portraits for the daughter of the Saudi Arabia ambassador and was hired to make portraits of the presidents of Costa Rica, Panama, and Ecuador when they came through Washington. The magazine work accounted for only 5% of his business, he says, but the portrait work that spun out from it made his living.

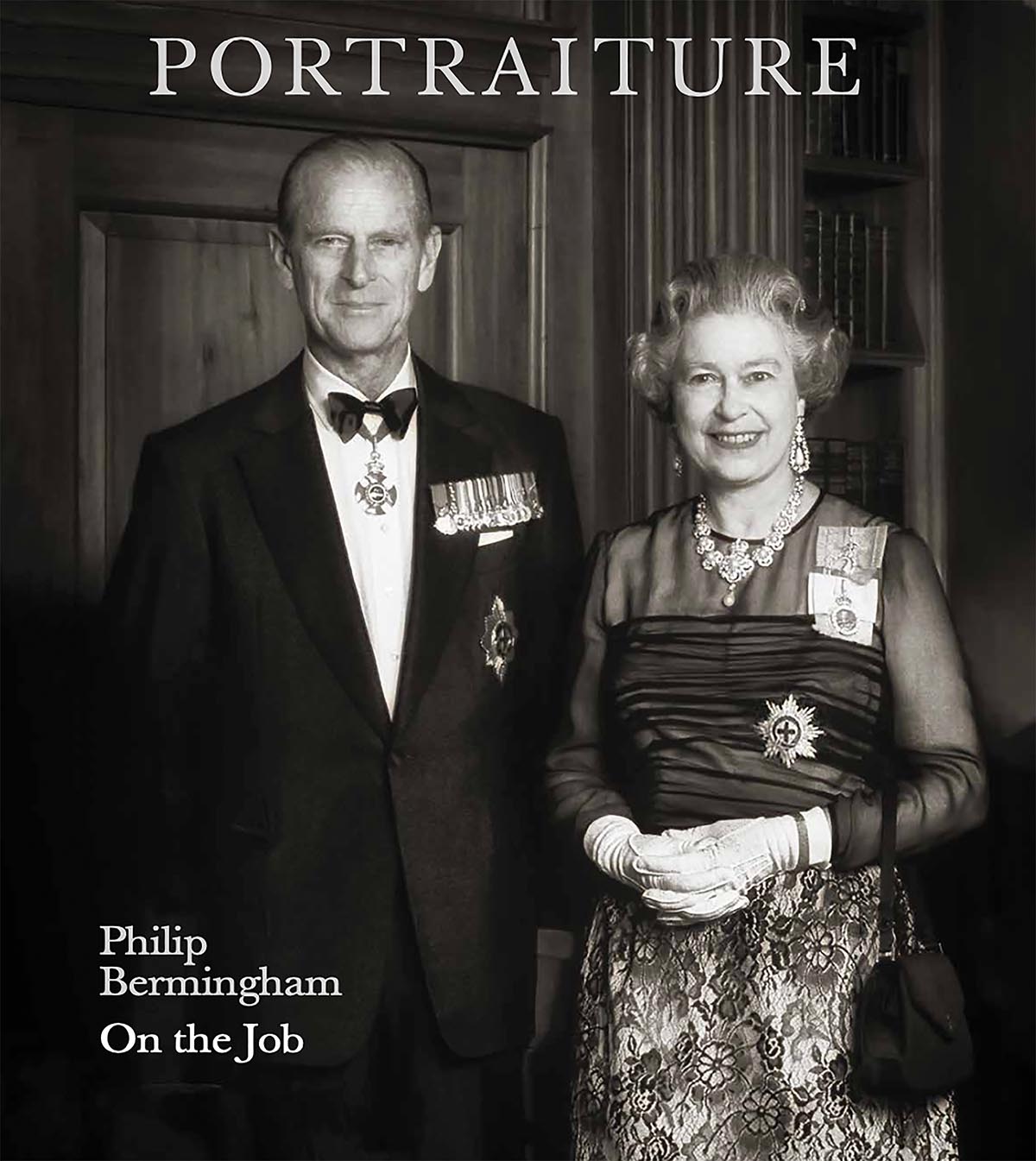

ROYAL TREATMENT

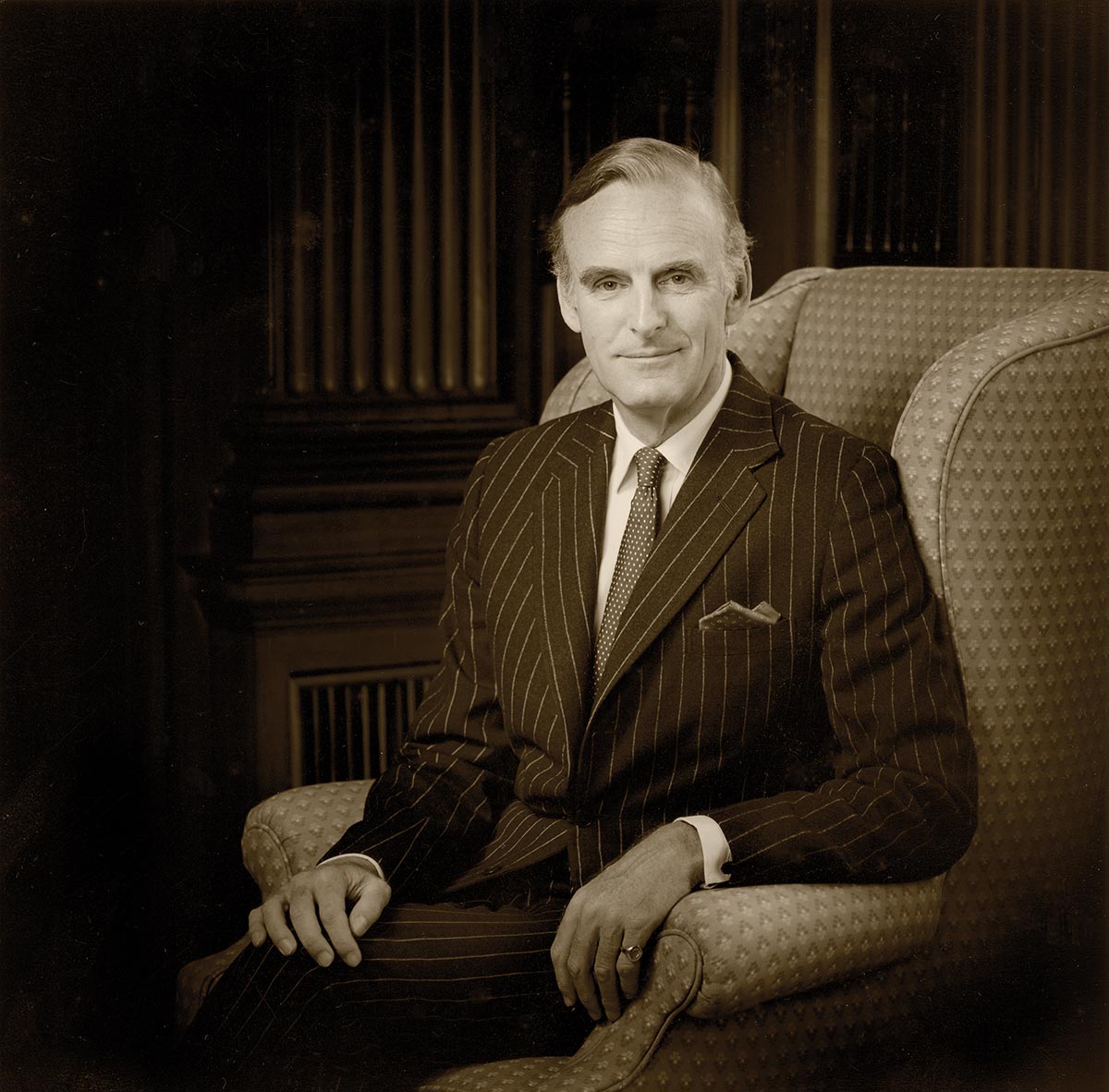

Through his ambassador sessions, Bermingham became friendly with British ambassador Antony Acland, then made a portrait of him and his second wife. That contact led to the highlight of Bermingham’s career: a 10-minute portrait session with Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip during a royal visit to Washington.

Bermingham was eager. He called ambassador Acland as well as Acland’s wife and secretary along with several other people as soon as he heard about the impending royal visit. Would the royals need a photographer? Embassy officials eventually called and asked if he could check his diary for May 17 to photograph the queen. “Can you imagine getting that call?” he says.

“Prince Philip could be notoriously grumpy at times,” Bermingham says, or he could be charming and lovely. On May 17, he was the former. While making photos, Bermingham asked the prince to put his hand on the chair. He said no. He asked him to put his hand in his back pocket. He said no again. He asked him to sit in a chair. He said no a third time. “I wanted the ground to just swallow me up,” says Bermingham. The queen was holding a handbag, and Bermingham asked if she could put it down for a moment. “She just kind of smiled and said no. I said, ‘Ma’am, I’m so pleased to see your dress is so nicely pressed because I had a dream the other night that I had to iron it.’” Everyone in the room, including the queen and prince, started laughing. “I got it,” he says of the capture. That little joke triggered a genuine smile and a twinkle in their eyes. Those little nuances make a difference, he notes. He made it the cover of his photobook “Portraiture: On the Job.”

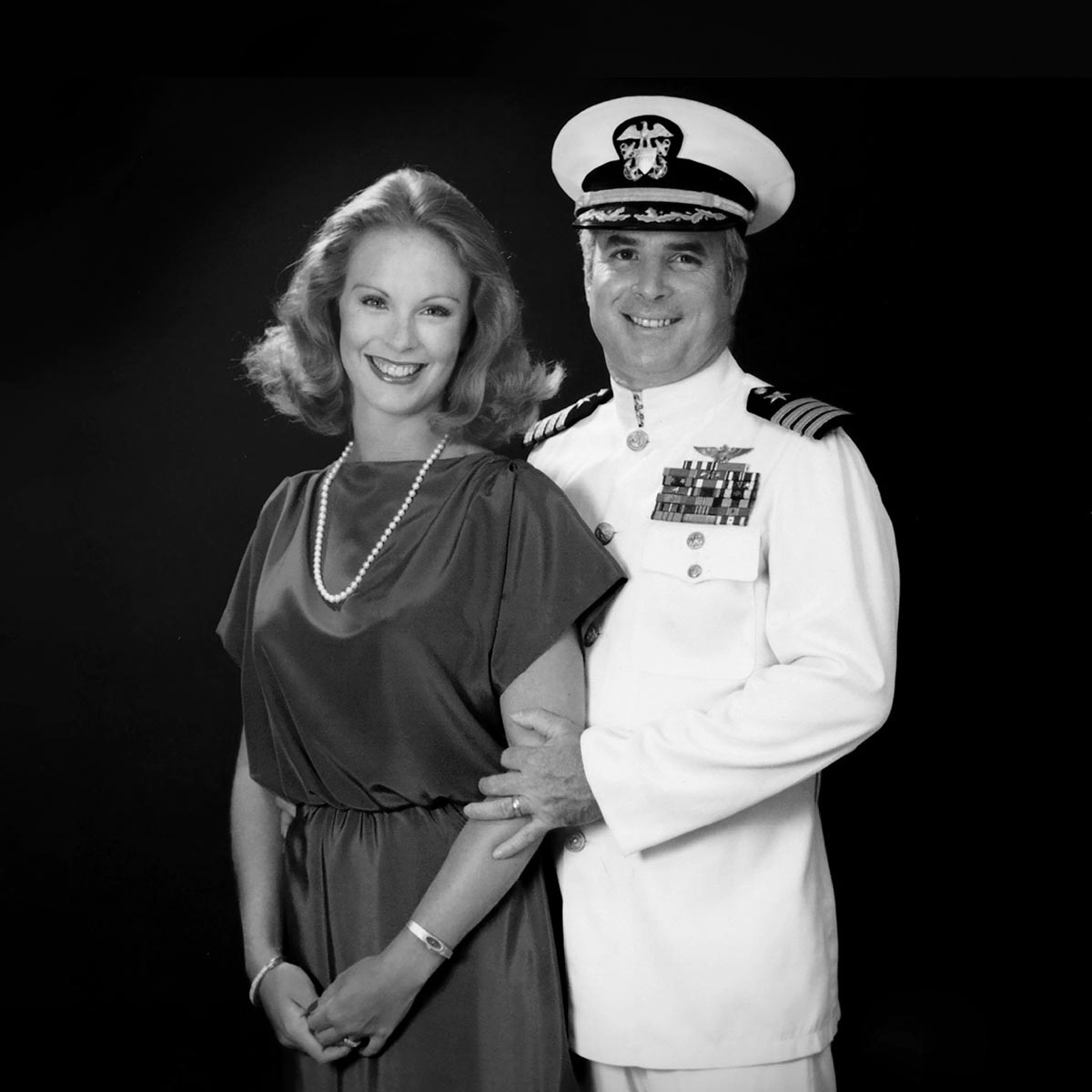

RUNNING REPUBLICAN

In the early 1980s, Bermingham got a call from Cindy McCain, who wanted a portrait with her new husband, John McCain. Cindy, who lived a block from Bermingham’s studio, found him in the Yellow Pages. During the session, McCain mentioned that he was about to retire from the Navy and was preparing to run for Congress. Bermingham told him that should he run, he’d love to do his photography. McCain took him up on the offer, and Bermingham photographed McCain eight more times.

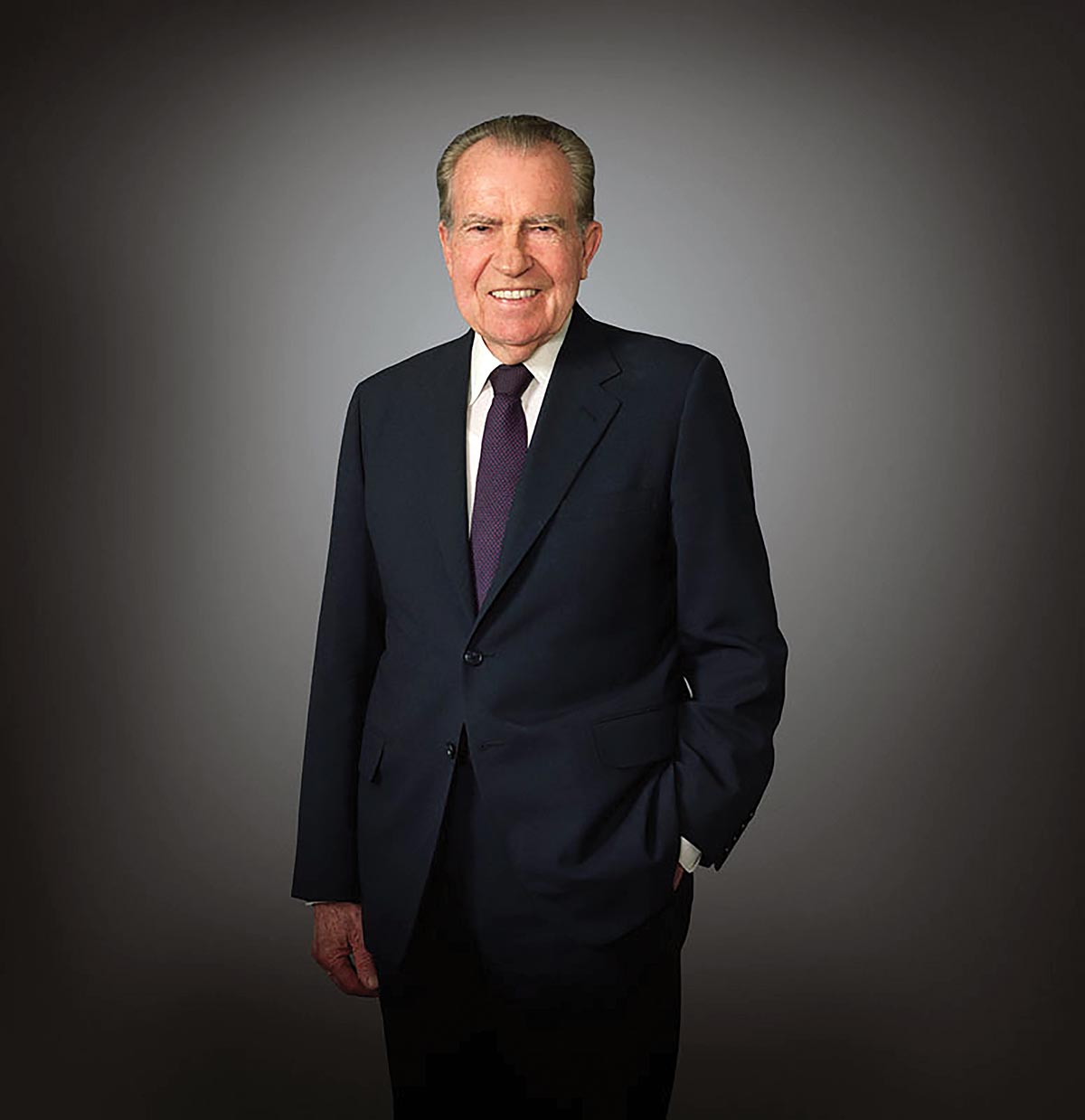

WATERGATE CONNECTION

The McCain portrait led to other sessions with Republican figures during the 1980s and ’90s, including former President Richard Nixon, whom Bermingham photographed for his 80th birthday, both alone and with his grandchildren. A representative from the Associated Press was present at the session and wired the portrait straight to New York. “The following day, the photo was published in 380 newspapers throughout the world, and a half-page picture of Nixon and his grandchildren ran in The New York Times,” explains Bermingham.

GOLDEN BARITONE

Bermingham was the last photographer to make an official portrait of Nixon before the former president passed away. Upon Nixon’s death, he was asked to appear on a local television station to discuss his photos and his experience with Nixon and his family. In the green room, also waiting to appear on television, was singer and record producer Lou Rawls and his publicist. Later, the publicist reached out to Bermingham and asked if he could make a portrait of Rawls while he was in town. “Every opportunity presents another opportunity,” says Bermingham. “It’s sort of magic.”

Amanda Arnold is a senior editor.