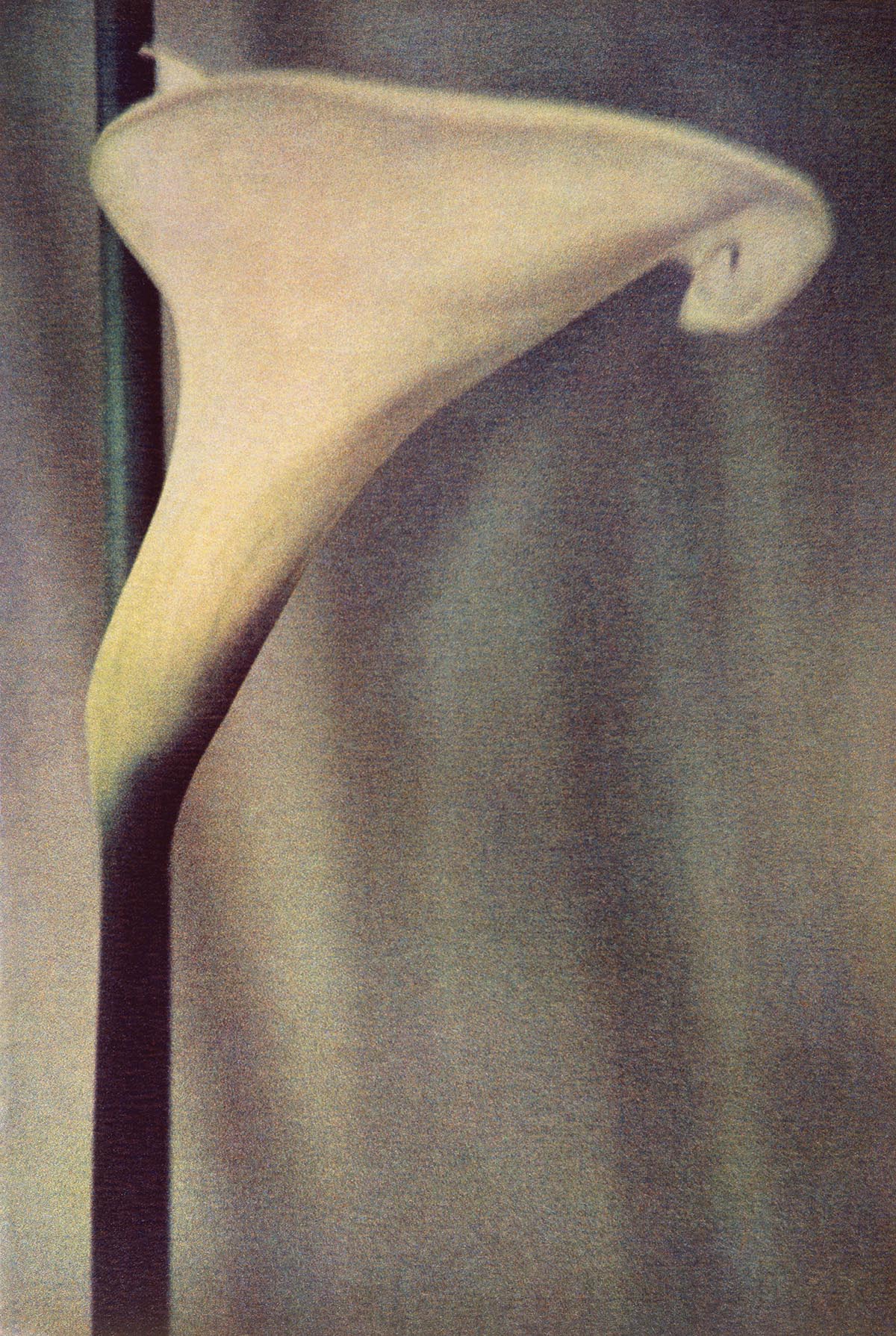

High above the City of Angels, the Getty Center is a beacon of light in the art world. It continues to shine with its latest exhibition, “Sheila Metzner: From Life,” on display through Feb. 18. Viewers of Metzner’s work, reproduced by the Fresson process, find a world where Pictorialism and Modernism blend seamlessly regardless of subject matter. And the exhibition title? “Those words came from many years ago, noticing how Julia Margaret Cameron signed her pictures, ‘From Life,’” Metzner explains. “Aren’t they all from life? It resonated with me.” She made it the title of her 2017 book, and Paul Martin, the Getty Center curator who selected works for the show from her archives in upstate New York and Brooklyn, thought it an appropriate title for the exhibition as well.

ALWAYS ABOUT THE WORK

Metzner’s life began in Brooklyn, New York, in 1939, and her parents recognized her innate artistic talent early on. Although they steered her toward becoming an art teacher, she detoured and pursued visual communications at Pratt Institute. After working at CBS in network advertising and marketing, she was hired by the Doyle Dane Bernbach advertising agency in a creative role.

“I was the first woman that was hired as an art director,” she recalls. “But they didn’t know I was a woman because my husband Jeffrey Metzner, who I had first met when he came in for a meeting at CBS, brought my portfolio up and showed it to the director of his group who said, ‘This guy is great.’ Jeffrey responded, ‘It’s not a guy, it’s a woman.’ So, they hired me from my work without ever meeting me.

“I think that’s my life story,” she continues. “It’s always been about my work. That’s the bottom line. I really try to stay out of exhibitions of women’s photography. There is no such thing to me. Every photographer is unique. Every photographer’s life and vision is totally connected to that being, that person’s soul, that person’s mind, and that person’s vision. It’s as unique as human beings are unique. None of us are the same.”

Concerned over the manipulative nature of advertising and wanting to refocus her priorities after having her first of five children, Metzner quit her job. “So, then I was a mother but I had friends in the industry,” she explains. “One, Aaron Rose, became a mentor. I told him, ‘I really don’t know what to do.’ He said, ‘You should be a photographer. You live like an artist. You’ve got a good eye, and you’ll be good at it.’ I was always taking pictures anyway. As an art director we all had cameras.”

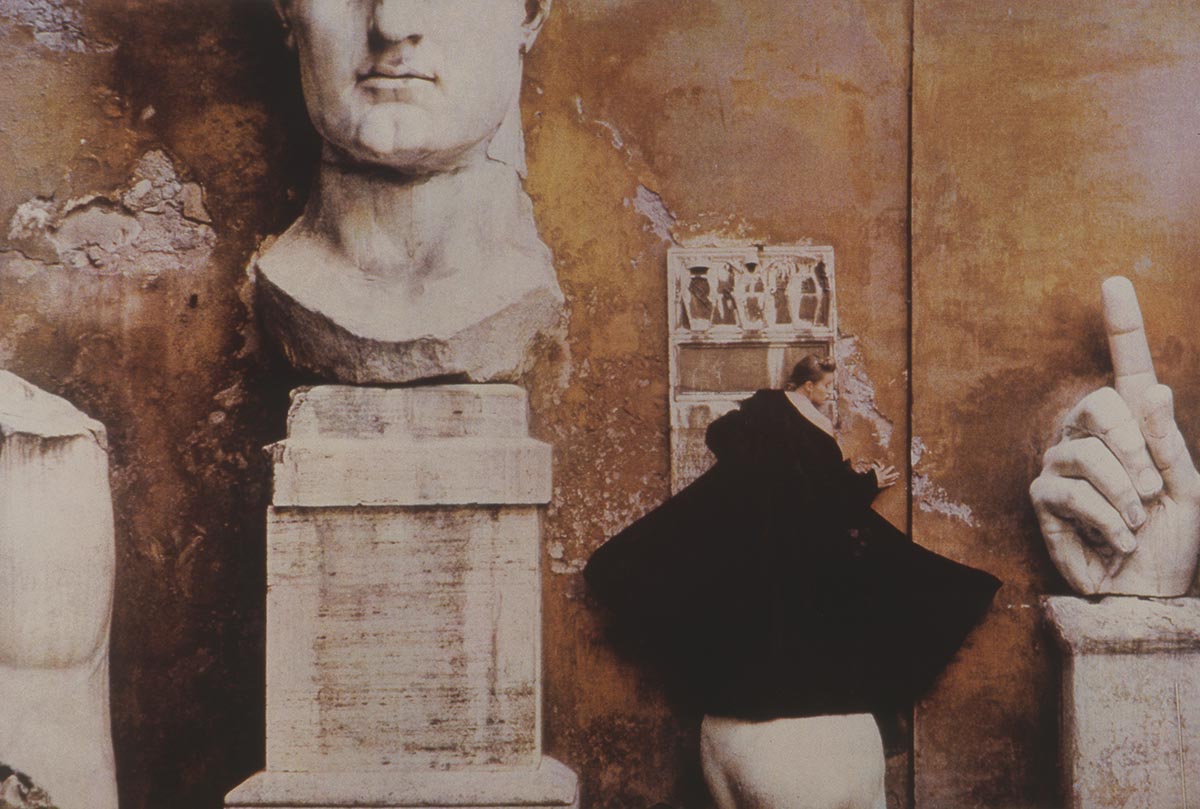

Metzner built a solid body of work over the next decade. She showed a selection of images from her first exhibition, “Friends and Family,” to John Szarkowski, director of the department of photography at the Museum of Modern Art. He purchased two for the museum collection and included them in the 1978 exhibition “Mirrors and Windows: American Photography Since 1960.” Metzner’s images were standouts, and commercial and editorial assignments soon followed, including fashion shoots for famed Vogue art director Alexander Liberman and early commercial assignments for Valentino and Elizabeth Arden. Her first book, “Objects of Desire,” published in 1986, led to dozens of exhibitions.

PRECISION PRINTING

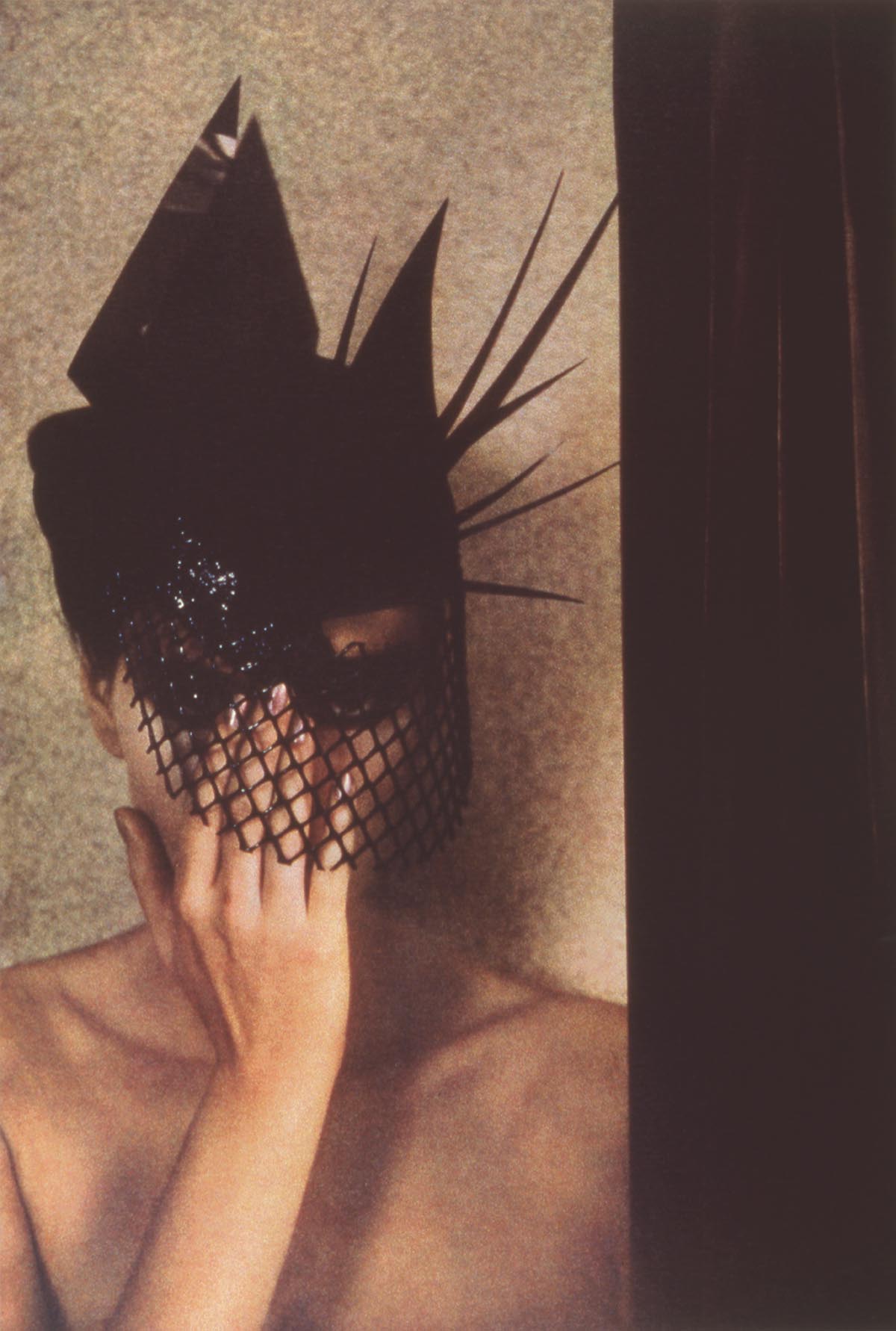

The photos on display at both the Getty Center and the Peter Fetterman Gallery were printed in the suburbs of France by the Fresson family, whose unique process dates to 1899. The process was first used for monochromatic prints and later to make the first direct color carbon prints. The process takes a staggering minimum of six hours per print.

While some attribute the look of Metzner’s distinctive imagery to the Fresson printing, she says that’s a misperception: “I went to Fresson because I wanted to print color at the time when there were these color printers that were very limited in their scale and papers. Every aspect of it was not color to me. I searched for many years for a process that was archival and could print faithfully what was in my 35mm Agfa 1000 and PolaPan chromes. I was called by Marvin Heiferman at Castelli Graphics, who said he found a process for me in the suburbs of Paris. It was Fresson. Their prints were more accurate reproducing what was in the chrome than C-prints and dye transfers. Also, with Fresson you could get a neutral gray, and almost all of my backgrounds are neutral gray.”

While she discovered her printer in Europe, Metzner found inspiration for her Brooklyn Bridge series in Asia and named it after famed Japanese woodblock artist Hokusai. “The reference is that most of his Mount Fuji series were, relatively speaking, views from the same place. Jeffrey and I bought an apartment that faced the Twin Towers on an evening when the sun was setting between them. I thought, ‘This is going to be really interesting.’ Then the towers went down within weeks, but the bridge was still there. I kept a camera on a tripod focused on the bridge so the whole series was done whenever something occurred that asked me to photograph it. It’s basically a series of the same object photographed from the same place with the same camera and lens at different times. Not unusual—I think [Edward] Steichen did that with a little tree outside his place upstate. I did two series on New York. The first one was ‘New York 2000.’ There’s definitely a Japanese influence; the photographs are quite two-dimensional. They’re flat. When I started photographing New York City at the request of James Danziger, I made the decision not to have any people in any of the images and to only shoot from rooftops and to only use PolaPan film.”

DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION

A combination of factors led Metzner to digital: Her favorite films, Agfa 1000 and PolaPan, stopped being manufactured, and clients stopped giving assignments because they wanted the immediacy of digital. She made the move from a Canon film camera to a Canon digital. “I had tried the Hasselblad, but I was so uncomfortable because I had been shooting 35mm from the beginning. When Canon came out with their digital camera, I did a couple of experimental shoots. Then I told Ralph Lauren and all my other clients, and they started working with me again. It didn’t make a difference that I was shooting digital because I had a digital person who was translating my raw files into what I saw. I could light the same way as I did for analog. The lighting was the same, the situation was the same. It was always flat.”

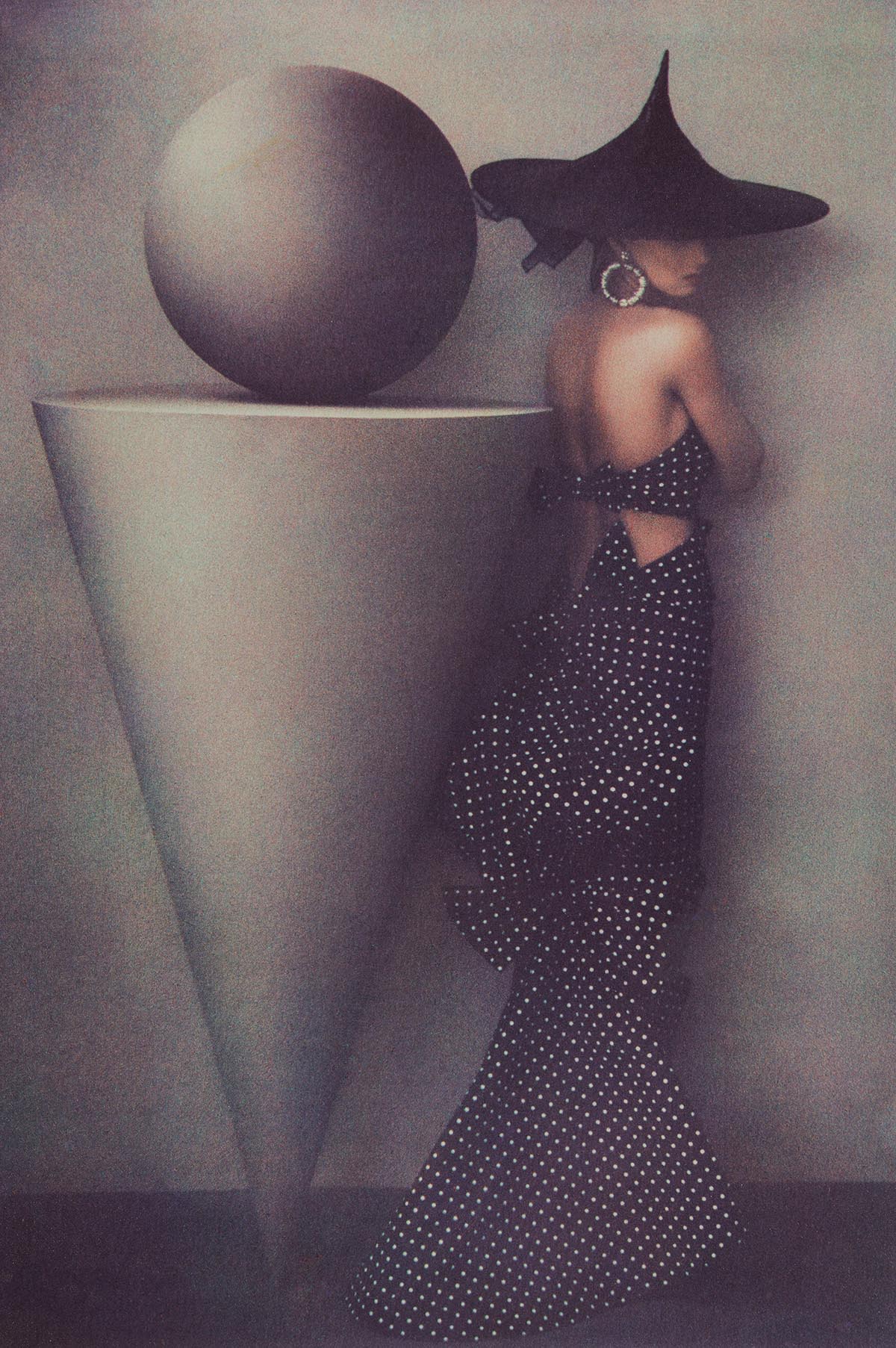

Metzner has preferred to work in low-light conditions throughout her career. “A lot of writing about my work talks about the process giving the work a style, but that’s not ever the way I saw it and that’s not the way it was. Fresson could print as sharp as anyone, and my work is sharp. I did use films like Agfa 1000 and also worked in extremely low-light conditions. Somehow form and color appear in a very different depth in low light. Life has a different dimension in low light. For the first number of years, I never lit anything; it was always daylight. I started to light, because I had to, when I had my first assignment in Paris for Vogue shooting couture. You could only shoot at night after the shows, so I rented HMIs to imitate the first light of my experience, which was two windows behind me a certain distance away, a wall in front of me, and no directional light coming from the right or the left. Since I’ve always worked in a soft low-light situation, that determined the grain of the film. I had to use a fast film such as Agfa 1000.”

A GLORIOUS LIFE

Metzner continues to reflect on her life behind and beyond the camera. “I was a mother and a cook and a housekeeper and at the same time had this incredibly romantic extraordinary life meeting these marvelous people and traveling all around the world. It was my destiny. I grew up in a family with no money. My parents couldn’t afford a set of encyclopedias, but someone gave my mother the gift of volume one of a set. It wasn’t even the Britannica. It was from A to E. But do you know how much is in A to E? Alaska, Antarctica, Africa, and E has Egypt. That was my earliest inspiration.”

“One thing really does lead to another, it’s really a miracle. You never know who you’re going to meet or what somebody is going to say that is going to change everything. My whole life is quite glorious in retrospect. We don’t know what’s leading us. We don’t know where we came from or what we are, and somehow we have to conform to this mysterious chaos that we exist in. And all people are different. You don’t know why you have become what you are. The thing you capture with a camera is as much a mystery to the rest of the world as it is to you.”

Mark Edward Harris is an award-winning photographer and writer based in Los Angeles.