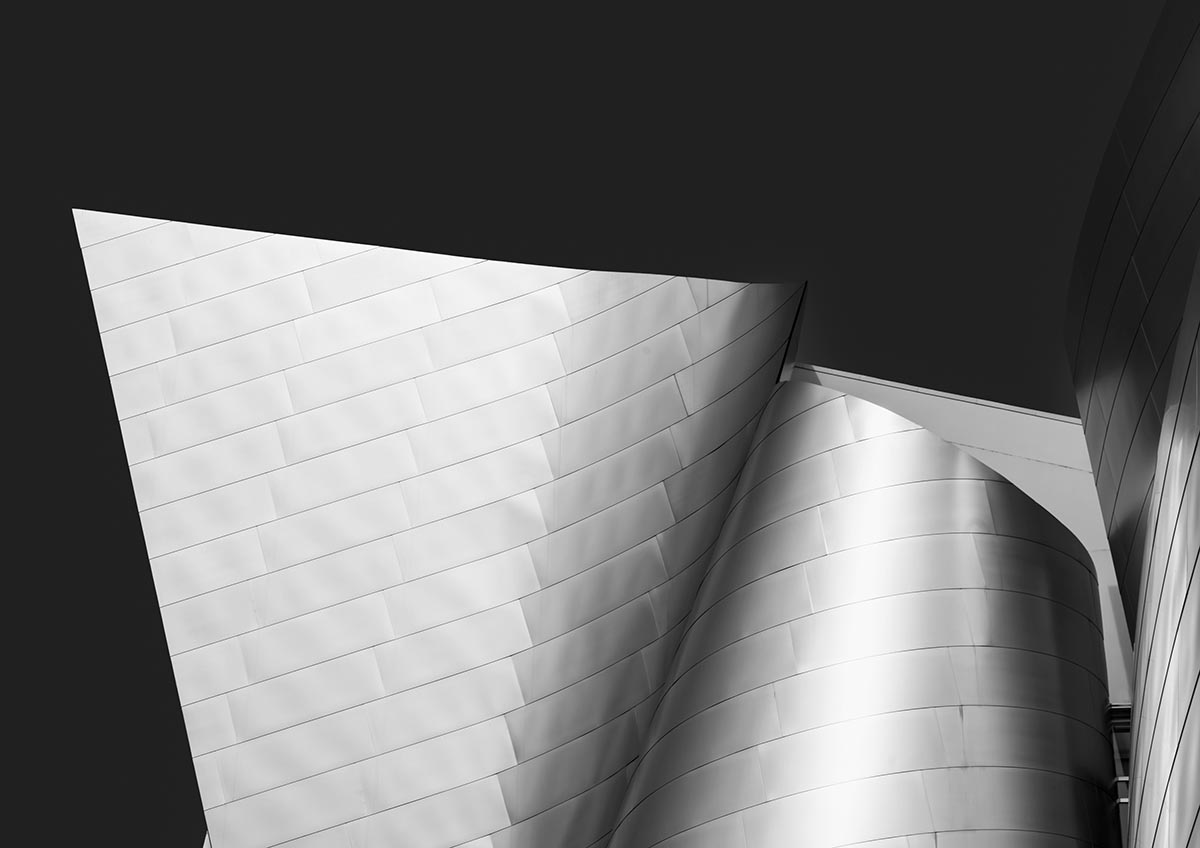

Photographers love the Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles. For obvious reasons. Designed by world-famous architect Frank Gehry, the landmark’s swooping, soaring, undulating stainless steel exterior calls to mind a multi-masted clipper ship with sails billowing. Its novel shapes and angles gleam in sunlight by day and in reflected city lights by night. It’s both a challenge and a delight to photograph.

Photographers and tourists have flocked to it since it opened two decades ago with the intent of capturing its iconic style that’s been described as “an architectural tour de force” by The New York Times.

POWER IN PREPARATION

In November 2017 Gigi Chung, an aspiring fine art photographer based in the San Francisco area, was planning a trip to Los Angeles. While she was there, she thought, why not visit Gehry’s much-praised masterpiece and see if she could, as she remembers, “shoot something different.”

Photographer Gigi Chung

“I’d fallen in love with—and been blown away by—the concert hall the first time I saw it, and I’d always hoped to photograph it someday,” says Chung. “But I also realized that because there had been so many great photographs taken of it, I needed to do something unique to make it mine.”

Pleased with some of the images she made that overcast day, Chung also knew she could do better. “I realized I had to bring something different to the table,” she says. To make better art, she concluded, she’d need better preparation.

After returning home she performed a deep dive, studying Google Maps to find the best locations for images she envisioned. She used the apps Sun Seeker and The Photographer’s Ephemeris to track the sun and pinpoint ideal places and angles to capture the interplay of light, shadows, and other effects she was looking for. She researched long-term weather forecasts to further optimize her plans.

Because, as she explains, “Great architecture has its own dynamic rhythm,” she knew she would need enough time to simply walk around and explore the concert hall, taking the time to discover its unique pulse and flow. “I wanted to combine strategic planning with a sense of exploration,” she explains. “Gehry’s work is so rich I needed a game plan as well as remaining open to experimentations and discovery.”

Her planning and patience paid off. She returned to the concert hall numerous times over the next two years, photographing from different angles at different times of day and in different seasons of the year. She produced a portfolio of minimalist black-and-white images she was happy with, called “Emergence.” This collection of architectural abstract images earned attention and awards. It was shown widely, including at a solo exhibition in Hasselblad’s Japan Tokyo Store Gallery in 2019. Three years later she was named a Hasselblad Heroine.

The concert hall photographs helped Chung make a name for herself. They also showed her that detailed planning as well as what she terms “the exploration concept of photography” were necessary for capturing the images she wanted. She has applied the same planning and execution techniques to subsequent projects that have taken her as far afield as Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong.

NATURAL INCLINATION

It’s not surprising that Chung, 53, has long been intrigued by architecture and urban spaces. “My father taught architecture, and when I was very young, I would tag along with him as he explored and photographed different buildings,” remembers Chung, who grew up in Hong Kong. “Architecture is not at all foreign to me; it is something I have been exposed to throughout my life.”

She also admits that she’s worked hard to retain the “innocence and open mindedness” she had as a child in her approach to photographic work. “I often say that I like to play in the sandbox, by which I mean that I am open to everything when I am shooting,” she explains. “I try to stay flexible. Sometimes the process of playing leads to new ideas, new images.”

A self-described minimalist, Chung distills the complex into the essential and has compared herself to a chef who, as she explains, “puts in only the essential ingredients, nothing more, nothing less, into his recipe.” Her compositions emphasize clarity and simplicity of form and are striking for their colors, shapes, and textures. As British photographer Jack Savage has noted, “The beauty of Gigi’s work is that it is minimal yet it is complex. It is minimal complexity.”

Chung has long been inspired by two of her father’s favorite artists, Dutch abstract painter Piet Mondrian and 20th-century American abstract artist Mark Rothko. “Again, these were influences I grew up with, and I have been attracted to their work throughout the years,” she says. Some of her images, particularly those included in the colorful series “California Fantasy,” are almost tributes to these painters. “Their ways of seeing, the way they both distilled complex scenes to a series of lines, forms, and colors appeals to me,” she notes.

Because much of her abstract work has a painterly aesthetic, she often includes a “hint of reality” so they won’t be mistaken for computer renderings. “Some people have actually asked me if an image was a photograph or a rendering,” she says with a smile. “Say a building has a sign on it that may not look perfect; I won’t crop it out because it makes the image look real.”

CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

After producing a series of award-winning portfolios, Chung continues to enter photography contests and regards them as valuable learning experiences. “Entering contests that have a specific theme makes me shoot with intent and be more consistent,” she explains. “Contests can also force me to curate or edit my images more tightly. It takes courage to omit the images that don’t fit into the theme of a contest.”

There’s another benefit to photographing images with the intent of submitting them for contests or exhibitions. “It gets you out there capturing images,” says Chung. “Photography is like any sport. However, instead of training for muscle memory, photographers train and exercise their eyes and brains on how to see. And you should never stop exercising.”

On a recent visit to Seoul, South Korea, Chung photographed, among other buildings, the futuristic Dongdaemun Design Plaza, which she described as “a dream come true.” She wrote about her detailed process of planning, exploring, and executing that photo shoot. Summarizing how special the venue is to local residents, she also explained why she continues to travel the globe to search out and photograph amazing buildings. Her intent, she admitted, is to show the rest of the world “how the people perceive the place with their eyes and how the place touches their souls.”

Her mission, as she learned much earlier, when photographing Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, is both a challenge and a delight.

Robert Kiener is a writer in Vermont.

View Gallery

View Gallery