To write that Carol Guzy follows in the footsteps of the greatest visual essayists in the history of photography would be a disservice. She walks side by side with the likes of W. Eugene Smith, Mary Ellen Mark, and other long-form documentarians who have given the world meaningful insight into the lives of people who find themselves in harm’s way. Guzy puts in the time and her keenly attuned eye to follow their stories. This comes at both monetary and emotional costs in the days when freelance photojournalists are facing tough economic realities.

Her efforts have been recognized by both peers and the public. To be awarded a Pulitzer Prize puts a photographer into an elite group. To take home four—in 1986, 1995, 2000, and 2011—is the stuff of legends. The first was for her coverage of the Armero tragedy following the eruption of the Nevado del Ruiz volcano in Colombia. The second was for her spot news coverage of the unrest in Haiti associated with Operation Uphold Democracy. The third was for her series on Kosovo War refugees. Her latest was for her camerawork documenting the aftermath of the 2010 Haiti earthquake.

Among Guzy’s additional accolades are numerous National Press Photographers Association awards; a Robert Capa Gold Medal Award; a White House Press Photographers Association Lifetime Achievement Award; a Chris Hondros Memorial Award; an ICRC Humanitarian Visa d’Or Award for news photography; and her latest, a 2023 Lucie Award for achievements in photojournalism. And her career remains on an upward trajectory.

Civilians rest in a bulldozer bucket after arriving at a medical trauma stabilization point while fleeing the fierce battle with ISIS in West Mosul, Iraq, on July 7, 2017.

THE ENTRY

Guzy’s entry into the pantheon of documentary still image makers began in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, a working-class town known for producing steel. Guzy earned an associate degree in nursing from Northampton Community College and planned to work as a nurse until a gift set her on a different path.

“When I was in nursing school, I used to take pictures of my dogs and flowers with a little Instamatic,” she says. “Seeing my interest in photography, a friend gave me a real camera. So, I took a darkroom class at the community college. Watching that first image come up in the tray of developer was the most magical defining moment of my life. I can’t remember what the picture was, but I can remember the feeling. I still feel it right now when I talk about it. That’s what pushed me to say, Let’s give this a chance.”

Soldiers attend a funeral for Denys Anatskyi, who died near Chuhuiv from mortar fire in Kharkiv, Ukraine, on June 24, 2022.

Guzy doesn’t consider her medical profession studies as time wasted: “Even though I thought nursing was an altruistic practical profession, it wasn’t the right fit for me. I wanted to be an artist when I was young, but growing up so dirt poor, I realized it was crazy to be a starving artist. Nursing seemed like a much more viable option. But our foundation is what inspires our eye and our way of seeing and reacting to the world, so there’s no question that nursing school was a valuable asset to helping build a sense of compassion and empathy. That’s why I gravitate toward humanistic stories.” It also no doubt fortified her constitution for the graphic scenes of suffering she would be exposed to.

Within a few years, journalism would have a new advocate to present the unfiltered reality of the human condition. But first she would have to learn the craft and climb the rungs of the photography ladder.

Photographer Carol Guzy

THE CLIMB

Guzy completed her nursing degree then entered the photography program at The Art Institute of Fort Lauderdale. “I had no inkling that journalism is what I wanted to do,” she says, so she started with portraiture and commercial photography classes. She found her niche when she took her first photojournalism class. Her instructor, Walt Michot, a newspaper photojournalist, would soon become her mentor and help her develop local stories with a critical eye.

Armed with a solid portfolio, she did two back-to-back internships at the Miami Herald then was offered a staff photographer position upon graduation. She joined the staff of The Washington Post in 1988, where she continued her award-winning photography. In 2014, she ventured into the precarious world of freelance photography.

Guzy sees freelance photojournalism as a double-edged sword: “I have a ton of freedom, which is great for making decisions on what stories to cover or not, but financially it’s been really hard,” she concedes. “I send photos to an agency, Zuma Press, to distribute. I know everyone in the business, but the hustle, making cold calls to editors or knocking on doors, is not part of my DNA, so most of the time I self-fund stories then hope to get them published afterward. I still have savings, so instead of going on vacations I do stories.”

A dog waits quietly amid unspeakable tragedy on the porch of a home flooded by Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans on Sept. 8, 2005.

Her coverage of Mosul, Iraq, as it was wrested from the hands of ISIS was one of the first international stories she did as a freelancer. The result was “Scars of Mosul,” a humanistic photo essay on the individuals caught up in the chaos of war. The graphic scenes in front of her lens are not for the faint of heart, but she feels compelled to go on. Guzy acknowledges that what she witnesses pulls on her emotions to their limits.

“Everything we witness changes us in some way. The more empathy you have, the more your heart breaks. When it’s a natural disaster it can be horrific scenes, but it’s something that is out of our control.

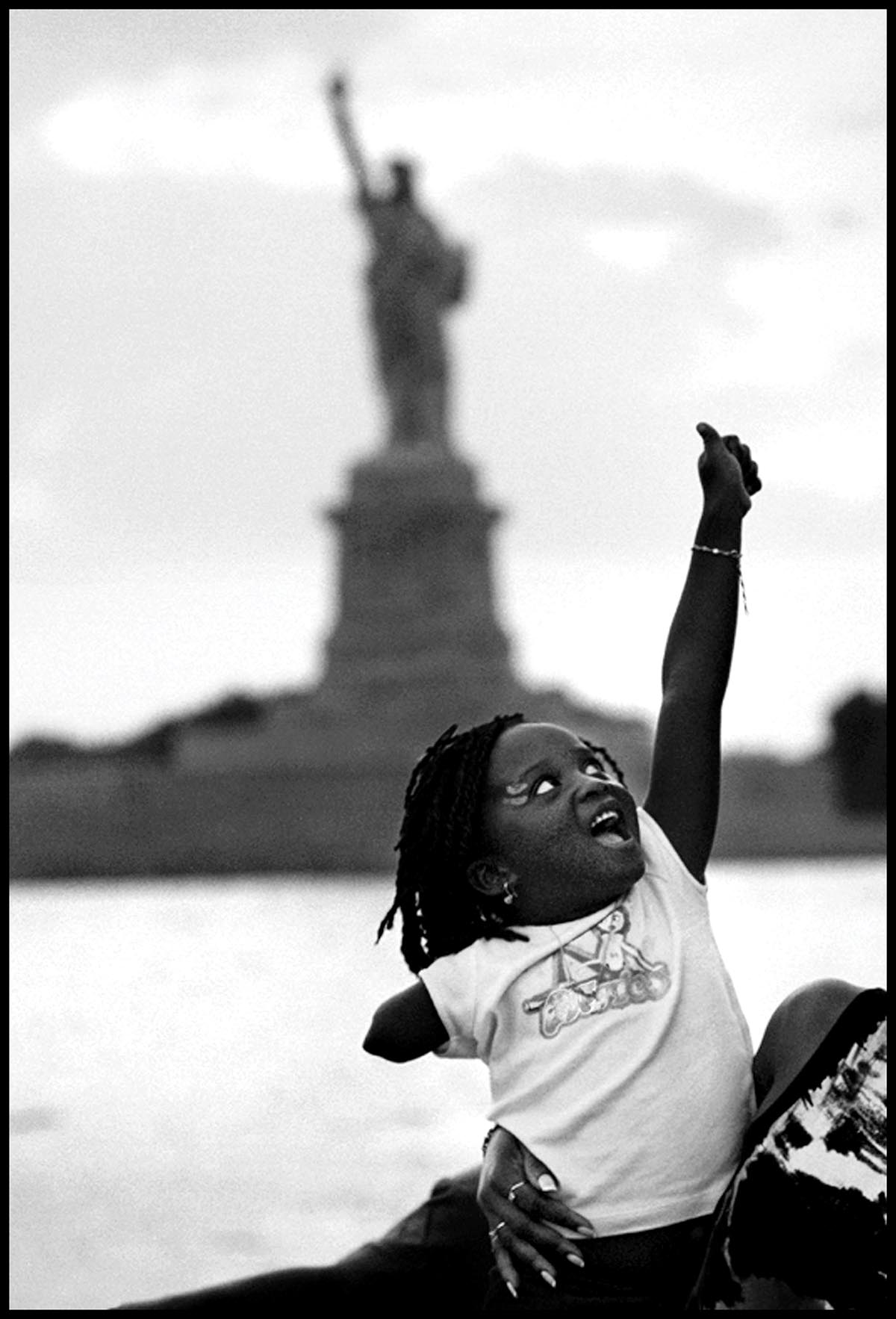

Memuna Mansaray McShane imitates the Statue of Liberty during a charity boat tour. She lost her arm when rebels in Sierra Leone shot through her, killing her grandmother.

And then you have the response, which you also have in conflict situations where you have these amazing angels that swoop in to transcend the adversity and help people. I try to focus on those moments of hope. Sometimes it’s a defense mechanism, but it’s important in our coverage to provide balance. But you see man’s inhumanity to man over and over again.”

“In Ukraine right now we’re witnessing it, the random shelling of civilians. I call it selective compassion that we as humans decide who deserves mercy and who doesn’t. To me the source of all the -isms—racism, sexism, speciesism, terrorism—makes humans capable of doing this to each other and to the animals and the earth we live on. To see that over and over and over again takes a toll. We’re not walking cameras. We’re not robots. We’re going to have the same emotions witnessing a lot of this stuff as the people that are actually living it. The difference is we have a delayed reaction like first responders—you have to put your own emotions on hold just to fulfill your role and do your job. When I edit is usually the time that breaks my heart.”

THE STORIES

In 2022 she traveled to Ukraine twice, the first for five months at the beginning of the war then later in the year for another month. “I would be a terrible wire photographer … getting it all in one frame and moving it quickly. I like to spend a lot of time and peel the onion of a story and have little nuances and more subtle images that build the whole package. I find it more meaningful. Once I start a story, I get pretty involved and it’s hard to let it go until I feel it’s the best it can be.”

Guzy doesn’t see the violence or aftermaths she records as something that happens only on the other side of the planet. “We have a war in our cities. Kids are killing each other. … It just seems like it’s escalating, it feels like it’s toxic and getting worse.”

“Media is the watchdog of society, and visuals drive the web, yet we were the first people to be cut on many newspaper staffs. There’s a bigger need than ever for truthful journalism with so much misinformation going out these days. We’re losing the long-form documentary story where you have a lot more depth and intimacy. It’s our challenge to make people relate to what’s happening. I feel you have to spend the time to get the genuine moments as a photographer. We don’t have that luxury anymore. Everyone loses in this scenario.”

“The media is always criticized for showing only bad news, the things that are unusual or horrific. All my life I’ve done positive stories. Those aren’t the ones people usually remember. I firmly believe we should have balance. We do tend to show the problems more than the solutions or the angels of mercy. But we do it, it’s just that people don’t pay as much attention to it.”

Guzy sums up the state of the union as it’s applied to her chosen profession: “There’s been such a lack of respect toward photojournalists in the United States. … Everyone I know in this business is a compassionate professional doing a lot of work to tell these stories that are vital in society and democracy. We do it because our heart and our passion is in storytelling. In Ukraine, people come up and hug you and thank you for telling their story. It’s really refreshing that they still understand the power of a photograph and a free press and democracy, which is what they are fighting for.”

Mark Edward Harris is an award-winning photographer and writer based in Los Angeles.

Tags: documentary photography

View Gallery

View Gallery