He had been so confident. Drew Doggett had been planning this four-week sabbatical to Nepal for months. But now, his plane sitting at its gate at John F. Kennedy International Airport, he wondered, Am I making a mistake? As more passengers began taking their seats, other nagging doubts bubbled up. Finally, he asked himself, Can I really afford to stop working for a month?

It was 2009 and Doggett, a 26-year-old photographer who’d been working in New York City for several years as a lighting and digital assistant with such superstar shooters as Mark Seliger, Steven Klein, and Annie Leibovitz, decided he needed a break from the glamorous, fast-paced, high-stress world of fashion photography.

He’d been thrilled to be assisting and learning from some of the best photographers in the business on assignments that allowed him to rub elbows with luminaries including former President Barack Obama, Madonna, Brad Pitt, and Desmond Tutu. But as he matured and gained experience, he felt he needed time away from the hectic work schedule to assess his future.

“My job was helping to ensure that the visions of the photographers I worked for came to life,” he once explained. “And I was good at it. But eventually I realized I wasn’t satisfied. I wanted to execute my own vision. There were stories I wanted to tell with my camera.”

Because he’d long been intrigued by the idea of documenting Indigenous people, Doggett arranged this trip to Nepal. Also, he reasoned, a month away from the hectic world of fashion photography would give him time to think about his career and where it was headed.

BEST DECISION EVER

Today, as he chats in his comfortable Charleston, South Carolina, photography studio, Doggett smiles when he remembers that nervous moment before he took off on what would become a life-changing trip. “I called a friend from the plane and confessed that I wondered if I’d made a mistake, leaving steady work and clients behind for a month of hiking in the Himalayas,” he remembers. “But there was something pulling me away.”

That something turned out to be the chance to document the lives and customs of the people of Humla, who had long been walled into a remote part of northwestern Nepal by the Himalayan Mountains. “I had done a lot of research and felt this would be an excellent opportunity to tell a story that was not widely known,” he says.

Throughout his month of hiking, he’d been threatened by avalanches, stranded by a snowstorm, lived with a local family, and experienced many more adventures. Doggett returned home with thousands of images and, most important, the answer he’d been looking for.

“High in the Himalayas, thousands of miles from anything that was familiar to me, I knew I had found my calling,” remembers Doggett. “I decided then and there to spend my life telling the stories of cultures, peoples, and places that moved me.” He would return to New York, say goodbye to the world of fashion photography, and hang out his shingle as a fine art photographer.

But could he make a living selling fine art prints? Doggett laughs heartily when he hears the question and points to a nearby paperweight, a college graduation gift he has long treasured. On it is written a question: “What would you attempt to do if you knew you could not fail?”

“I guess that pretty much sums up my personality,” he says. “I like a challenge. I knew I was taking a big risk, but I thought that if I used my camera to show parts of the world that may be unsung or at risk, I could make something unique. And I hoped that would resonate with people.”

He also realized, he explains, “I could take the aesthetic that I had come to know and love—the visual language of fashion photography—and apply that, with all its nuances, to subjects that were more meaningful to me.”

70,000 MILES

Today, some 14 years after his Himalayan epiphany, Doggett is a successful fine art photographer. He’s published several coffee-table books of his work, and his prints can be found in private and public collections around the world, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art and the Mariner’s Museum. His more than 120 awards include a distinction from the Royal Photographic Society, and his images have been published in magazines including Outside, Conde Nast Traveler, Architectural Digest, and others.

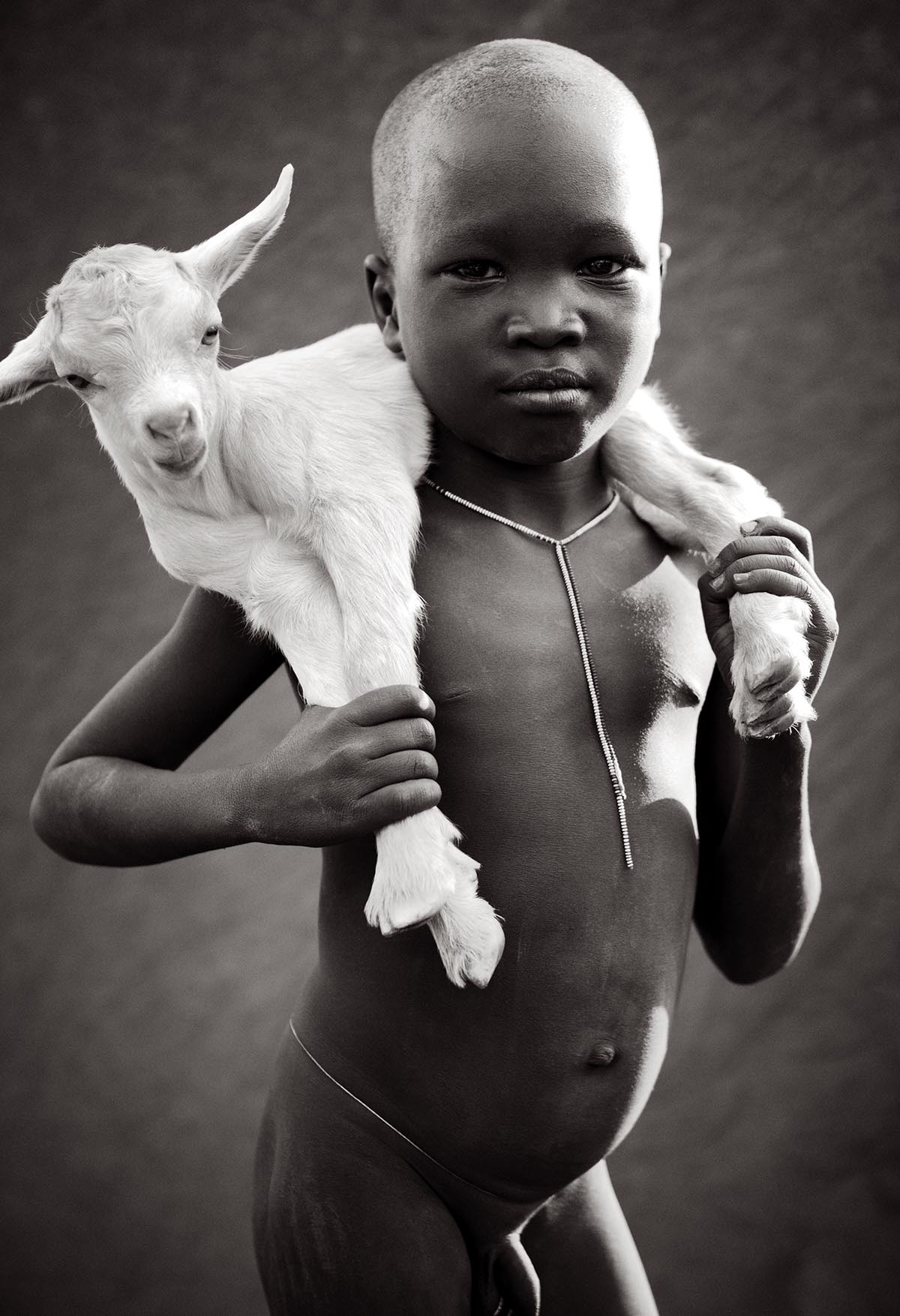

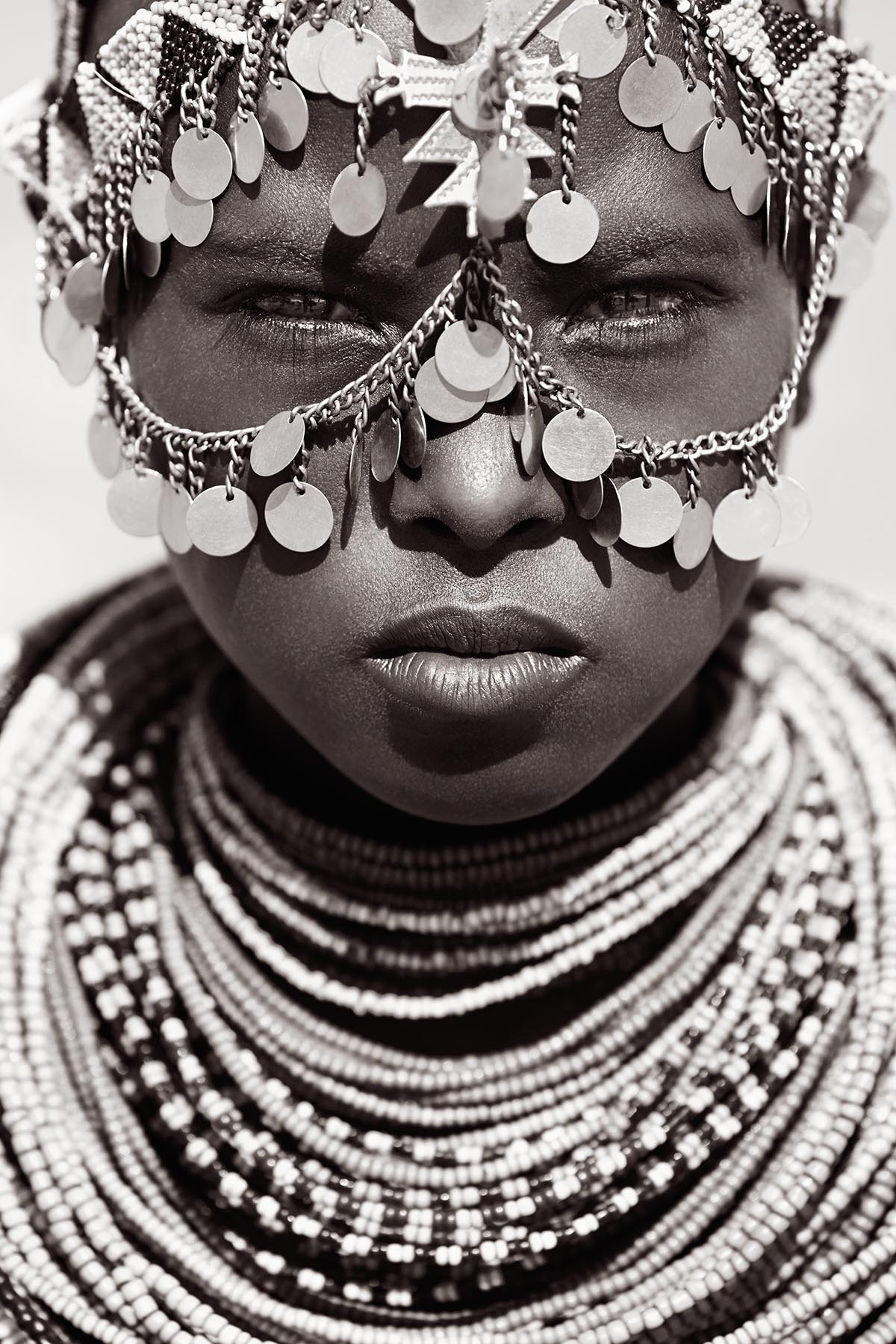

After returning from Nepal he traveled to Ethiopia to document the lives and culture of the semi-nomadic tribes in the Omo Valley, often referred to as the Cradle of Humankind. He’s become a frequent traveler to Africa and logs about 70,000 miles a year on self-funded excursions to—so far—more than 40 countries. Since his first series, “Slow Road to China,” which featured people of the Humla region of Nepal, he’s completed 16 more. Most of his photographs are sold in limited edition runs of 15 prints.

His work has taken him across the globe—to Rwanda to document the mountain gorillas, Iceland to photograph its white horses, Namibia to document some of the world’s largest sand dunes, and on a 14,000-mile trip through the American West. Some expeditions are more productive than others. He once traveled more than 1,000 miles through India and returned home with only one keeper—a striking image of a Bengal tiger.

He rarely accepts commissions, preferring to pursue what intrigues him. To choose subject matter for his series, he says, “I ask myself a range of questions. Will it stand the test of time? Does it represent a sense of shared humanity, and is it a form of beauty? Has it been done before? And lastly, would I want to wake up every morning and see these images on my own walls? I want my image to invite a viewer into an ongoing conversation with it as long as it’s on the wall.”

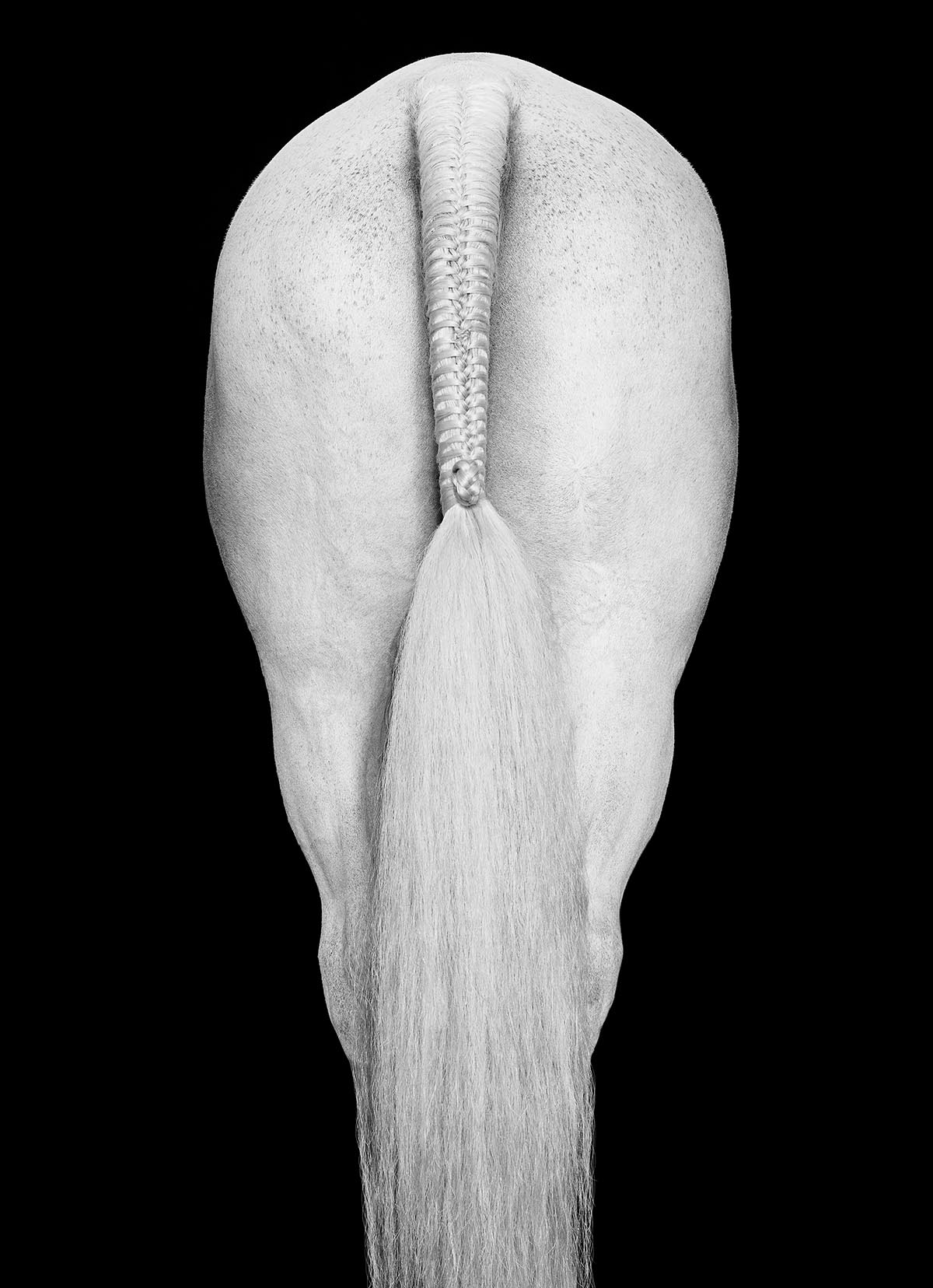

The 39-year-old father of two often returns to a destination to complete a series of images. For example, to produce his self-published book, “Wild: The Legendary Horses of Sable Island,” he spent more than 70 days on the 26-mile-long uninhabited island off Nova Scotia from 2012 to 2019.

“There’s no place like Sable Island. It’s a place where time stands still,” he explains. “The 550 wild horses there have become my muses. Every time I go there I feel inspired.” In a forward to the book, English primatologist Jane Goodall called Doggett’s book “truly a triumph of art, tenacity, and a passionate vision of the love of the wild.”

Doggett’s style has been described as “Vogue meets National Geographic.” Concedes Doggett, “It’s pretty accurate. Fashion has greatly influenced the way I see the world and I approach a lot of my subjects now with the same minimalist, idealistic aesthetic I learned and used in fashion photography. Fashion uses a visual language that is familiar and that people can relate to. I am heavily focused on form and composition. I am also a storyteller.”

He notes that he’s attempted to avoid being pigeonholed. “For example, I never wanted to be labeled as strictly an equestrian or a wildlife photographer,” he explains. “I feel that would prevent me from having the creative freedom to continue to evolve over the course of my career.”

CORE VALUES

Ever since his first trip to Nepal, Doggett has made it a point to give back to the communities he is documenting. He donated the proceeds from his book “Slow Road to China” to the Nepal Trust to fund healthcare services for the Humla villagers he photographed and lived among.

He often partners with charities and donates proceeds from his print sales to them. “Giving back to my subjects is a core part of my practice and ethos,” he explains. After working with Africa’s Tsavo Trust to locate and photograph super tusker elephants in Kenya, he donated a portion of his revenue from that project to the charity.

He’s also generous with advice to photographers navigating the business of fine art photography. “I never had a mentor, and [I’ve] learned about the business mostly by watching other photographers and making my own mistakes,” says Doggett. “This industry is still very opaque so I enjoy helping others—giving back—when I can.”

What’s next for this globetrotting award-winner? “Lots of travel,” he says with a wide grin. “And lots of storytelling. I’m off to Svalbard in Norway soon. Then to South Sudan for three weeks, and after that, Alaska.” He pauses, takes a deep breath, and adds, “Oh, almost forgot, I’m also going to Kenya twice this year to continue my documentation of East African animals. And I can’t wait!”

Robert Kiener is a writer in Vermont