Fine art photographer Aline Smithson smiles broadly when she remembers “the day the gods smiled down on me ... several times.”

Brushing locks of thick blonde hair from her face, she recalls, “It all started in a garage. Or to be more exact, at a garage sale near my home here in Los Angeles.”

Searching through the sale in 2003, the self-confessed shopaholic spotted a small print of the famous 19th-century painting “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1” (popularly known as “Whistler’s Mother”) by James Abbott McNeill Whistler. The former college art major admired Whistler’s paintings, and when she spotted the print of this classic she was inspired. “It struck a chord in me,” she explains. “I’d always loved the composition of this painting, and I felt I could explore it through my photography, perhaps as the basis for a photographic series.”

She bought the print, stashed it in her car, and set off to scout two other nearby garage sales. At one sale she found a chair much like the one in Whistler’s painting. “Again, something clicked,” she remembers. “And I could see my series taking shape.” At another sale she spotted a kitschy 1950s painting of a cat, a leopard coat, and a hat and realized she had the perfect props to produce a modern, humorous take on Whistler’s classic. “It was like a sign telling me to proceed,” she says.

She used the props to compose a scene that mimicked Whistler’s composition and asked her mother, Katrine, who was then 83, to wear the odd getup and pose expressionless in the chair. “She thought the idea was weird but played along wonderfully,” says Smithson.

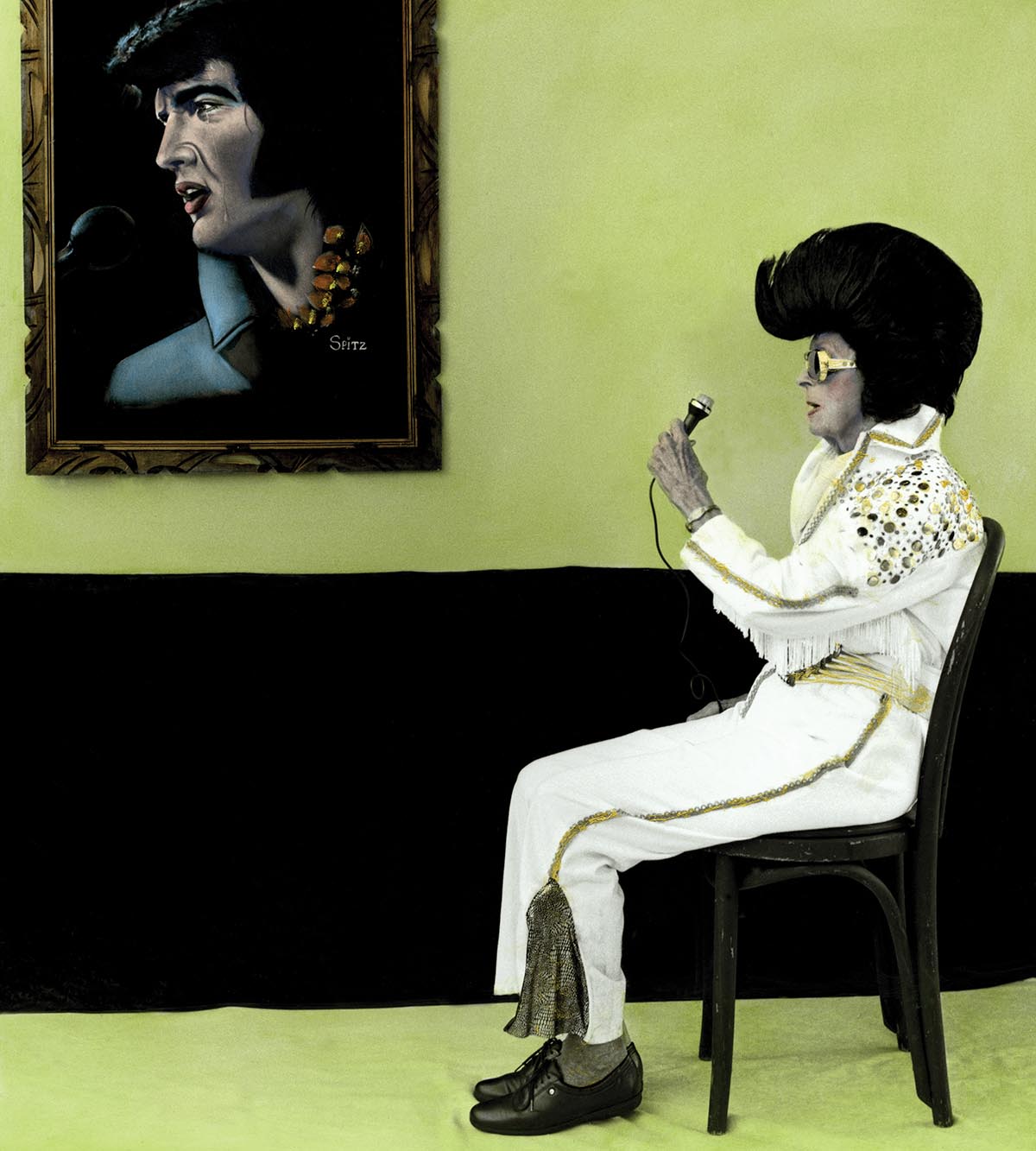

The quirky, black-and-white photos, which she hand-painted, proved popular, and Smithson produced a series of 20 over two years that she titled “Arrangement in Green and Black, Portraits of the Photographer’s Mother.” Each featured her mother in a series of offbeat outfits—safari suit, grass skirt, Elvis jumpsuit, and more—each of which Smithson found at garage sales, thrift shops, flea markets, and online.

Smithson elected to hand-paint each print because, as she has explained, “It is my intent to have the viewer see the work in a historical context with the addition of color and at the same time experience Whistler’s simple yet brilliant formula for the composition.” The images were a hit. “The series helped me make a name for myself and has proven to be my most popular, bestselling series so far,” she says. It has been shown all over the world and continues to attract eager collectors.

Like all of Smithson’s work, the “Green and Black” series reflects her drive to, as she explains, create something different. “I’ve often said that all of my work is a form of self-portraiture,” she says. “What I mean is that my work always involves subjects I am interested in, that fascinate me. I remember my mother asking me, when we were creating the series together, ‘Would anyone be interested in these?’ I told her I didn’t care; that wasn’t the point of my work. For me, my art—including the series with my mother—has always been about freedom. It’s something I like to explain to my students: Be free and find your own voice.”

PROJECTING HERSELF

After a career as a fashion editor in New York City, Smithson and her husband moved back to her hometown of Los Angeles, where she began studying and exploring photography. “Once I realized I could make art with a camera, I was off and running,” she explains.

In addition to working as a fine art photographer, Smithson has long led photography workshops and private tutorials and provided instruction at schools such as the Los Angeles Center of Photography. She also edits the photography website Lenscratch, which she founded in 2007. She’s published six photo books, and her work has been exhibited in more than 40 solo shows around the world.

“I have always admired photographers and photography,” explains Smithson. “It’s because we are active seers; we look at the world in a profound way. I’ve always had this crazy idea that, when I am driving through Los Angeles, I could project myself into the car next to me and go home with those people and find out about their lives. That’s what photography feels like to me.”

From her earliest days Smithson has been a film devotee. “I have resisted the urge to go digital,” she explains. She owns a lot of older cameras but has been using the same twin-lens Rolleiflex and Hasselblad cameras for years. “I am in love with the slowed-down nature of working with film. I even treasure the process of unwrapping my film, loading my roll of 120 film, and waiting to see the results. It makes me feel connected to photographic history. Also, there is a nuance to the light and color in film that doesn’t exist in digital images.” She confesses she rarely uses the term “gear” because, as she notes, “I think of the camera as a partner, not a thing.”

Smithson explains that she edits in camera and makes very few images, often just three or four for each setup. She admits she once bought a digital camera but never took it out of the box. “I gave it away,” she remembers. “I am also so attracted to the square format. I often think that’s because some of my biggest influences when I was growing up were album covers. I am still amazed by how much can be conveyed in just one square image.”

DIGITAL BLACK HOLE

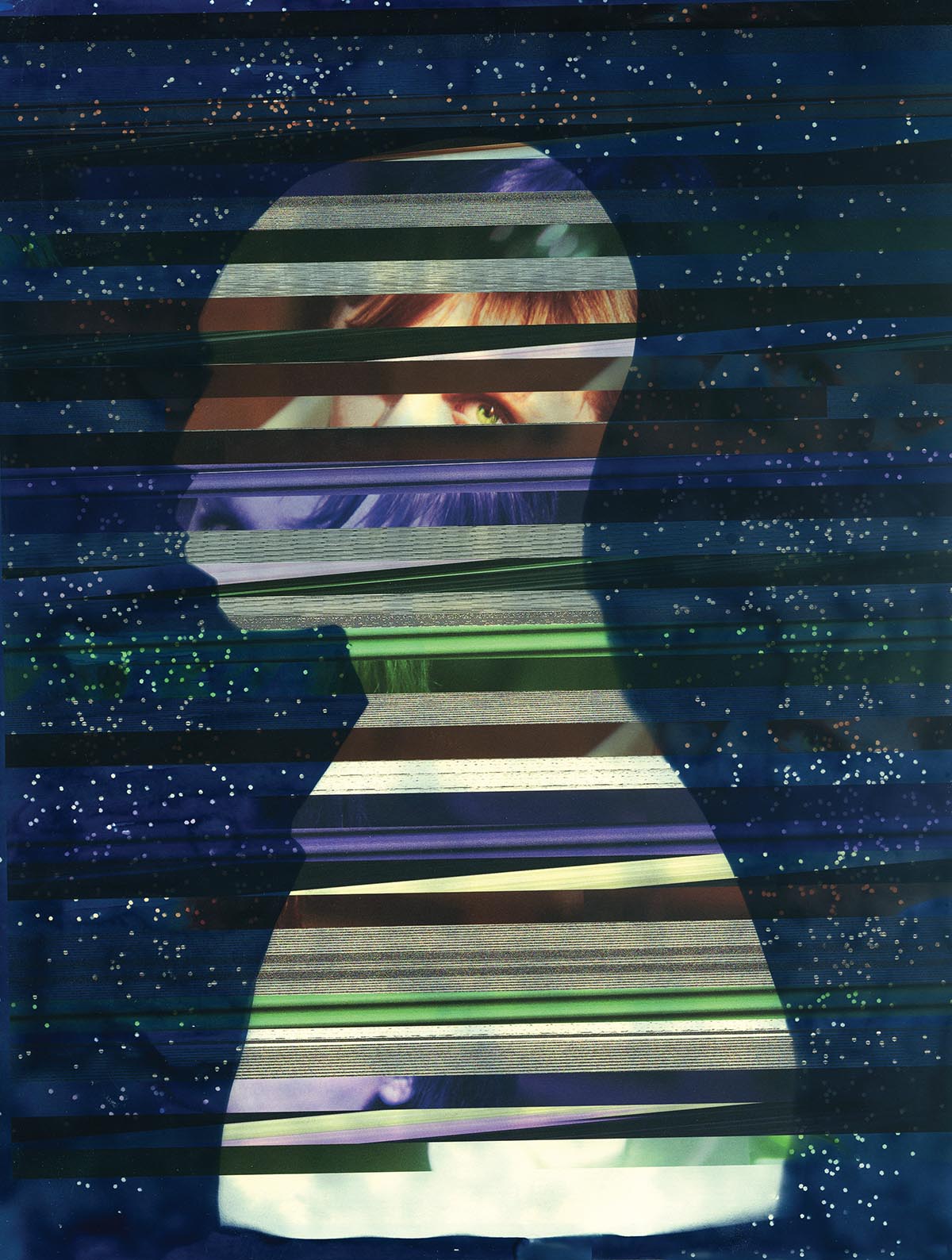

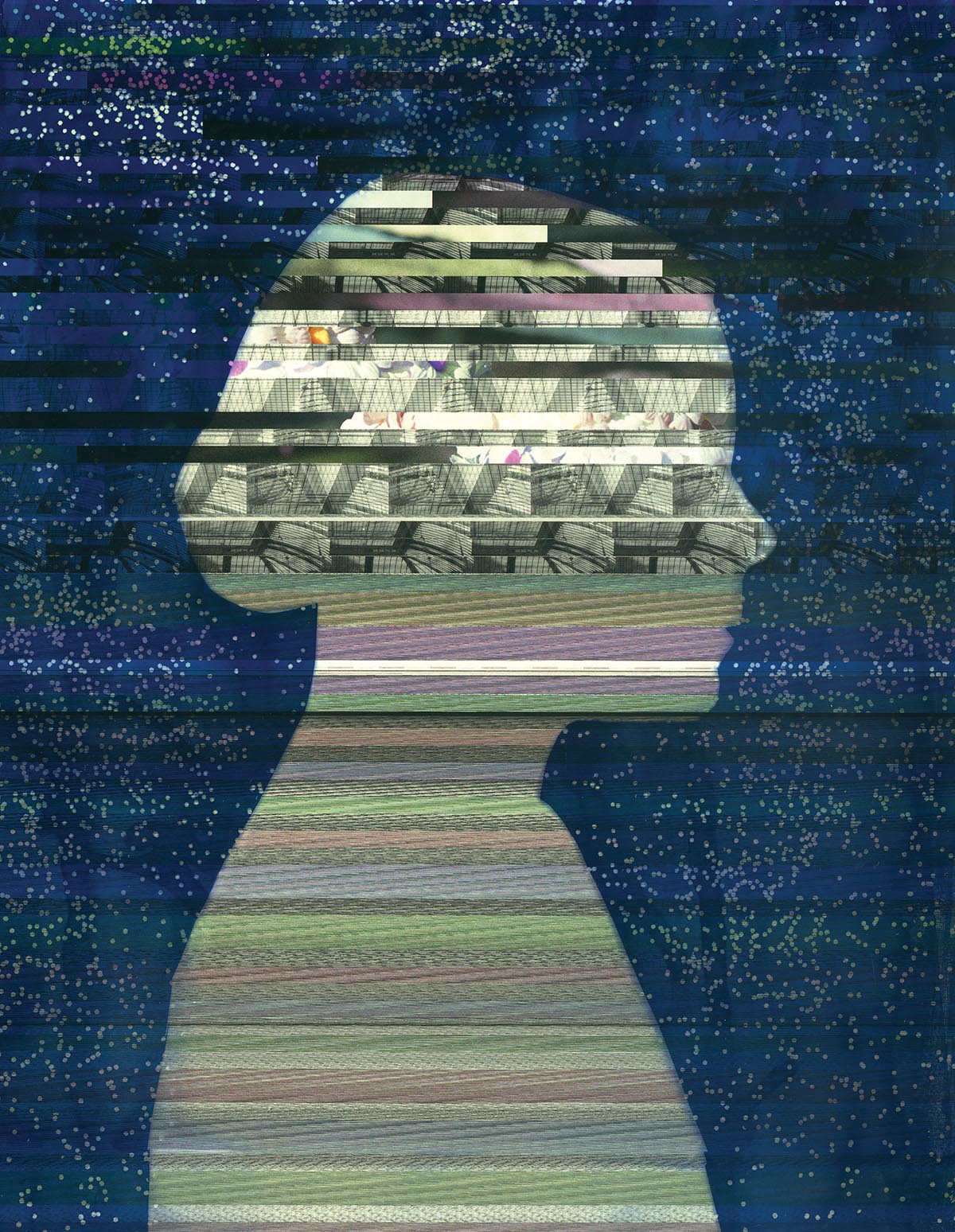

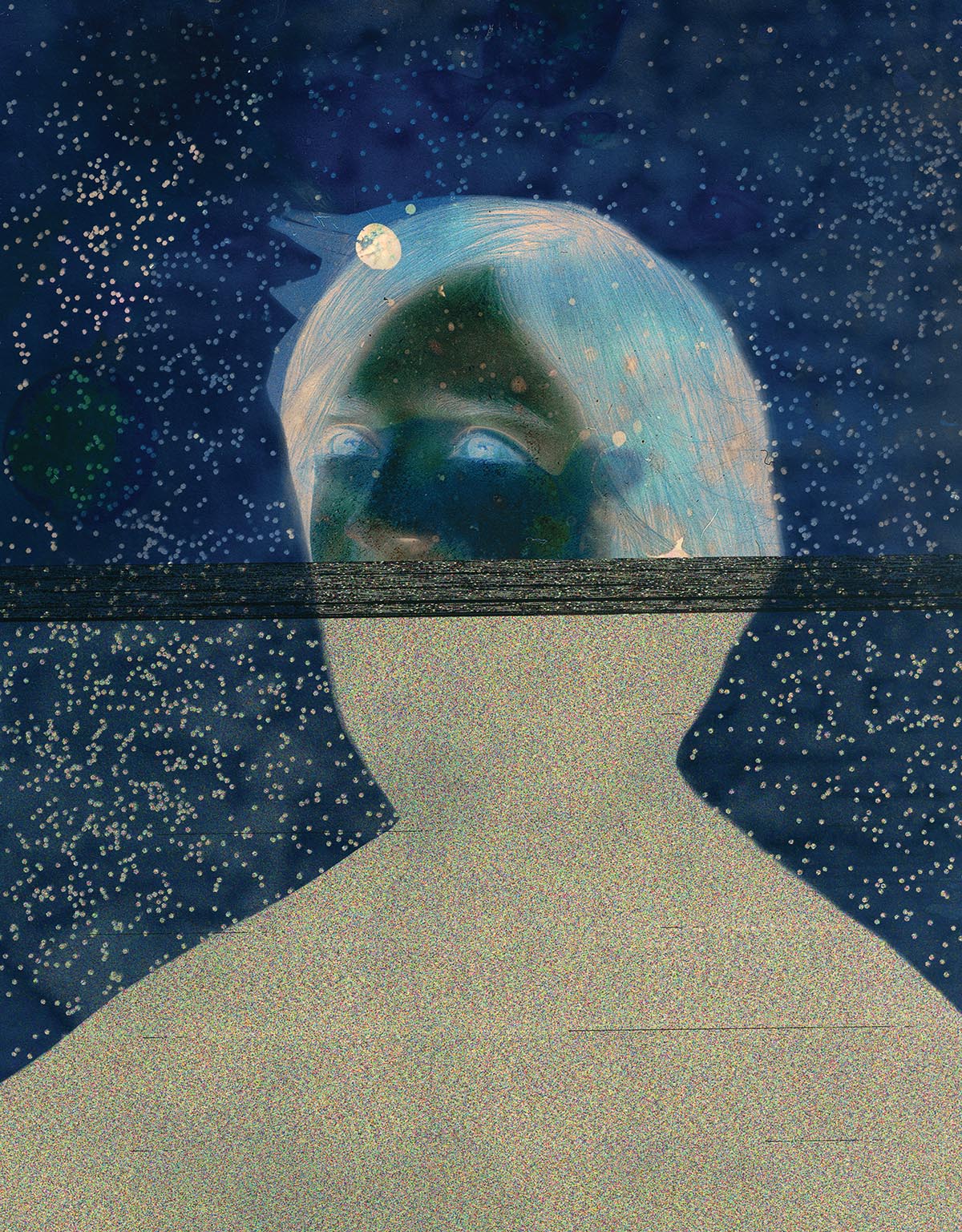

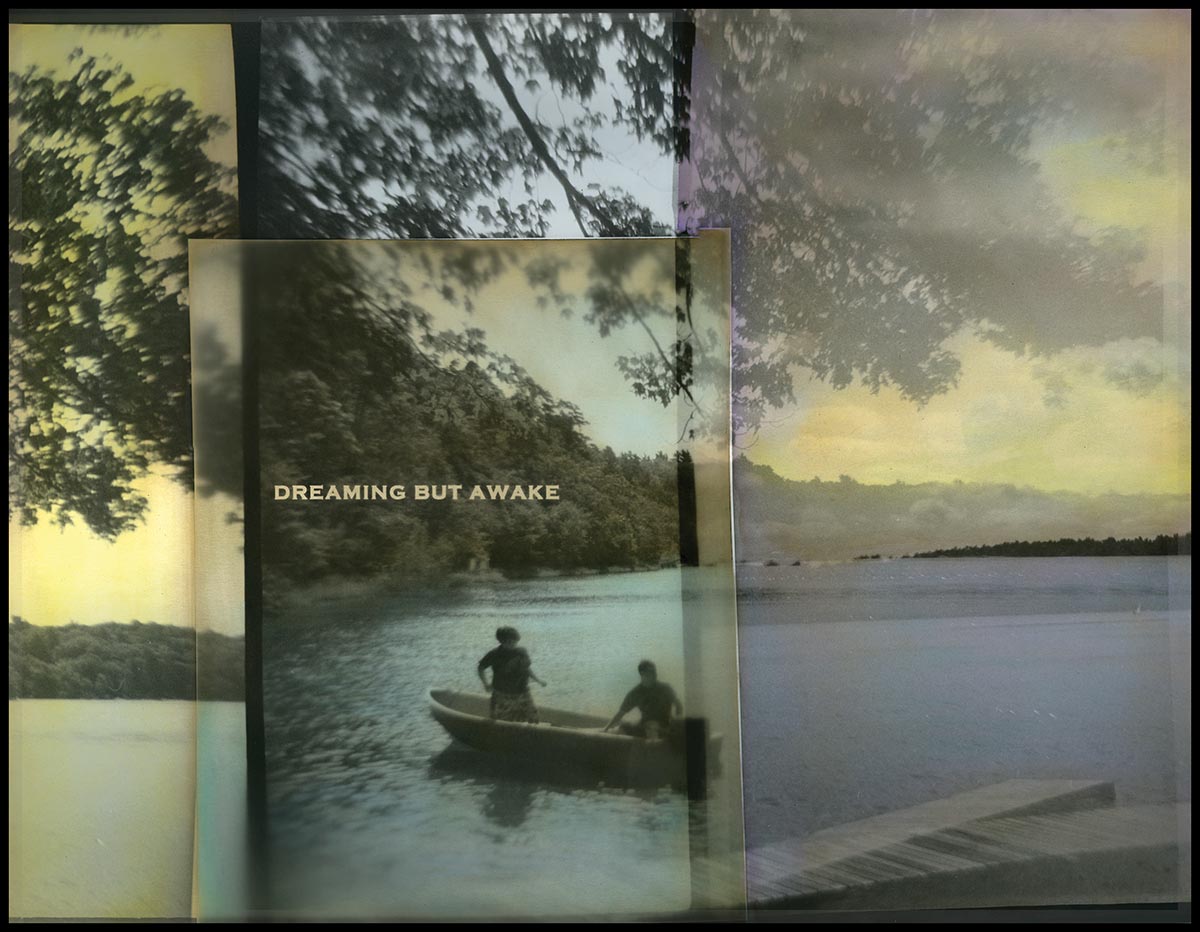

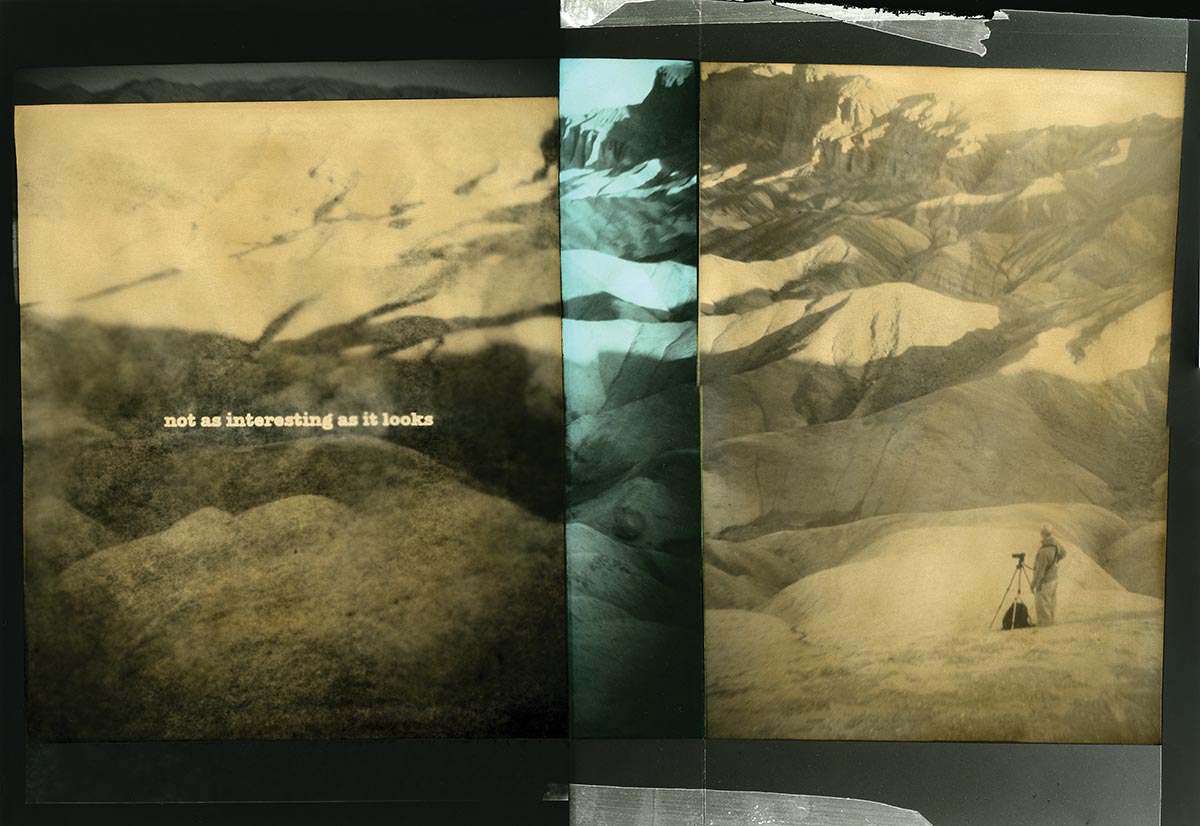

Smithson’s preference for analog over digital proved to be the inspiration for one of her most intriguing series of portraits, “Fugue State Revisited.” After scanning some 20 years of her negatives to a hard drive, that drive eventually failed. “About only half of the files were recoverable, and that got me thinking about how so many of the digital images we produce today could eventually disappear,” she explains.

To illustrate this danger, she used some of those damaged files as the basis for this series. She was making a statement about the fragility of digital files. As she explained in the notes for the series, “I use silhouettes of portraits from my archives as a way to conceal and reveal the corruption. By using historical processes to create a physical object, I guarantee that this image will not be lost in the current clash between the digital file and the materiality of a photographic print.”

“Hard drives have expiration dates,” says Smithson. “Prints will survive, but what about all these digital files?” While we can look at family photographs that were printed over a century ago, a CD of files from just 10 years ago may be unreadable.

“I worry about the danger of a digital black hole. Look at what has happened to music,” she explains. “We don’t have any contact with anything physical anymore. No album covers. … That could easily happen to photography.”

IMMORTAL PRINTS

Smithson’s mother Karine died at 85 before she could see the entire “Whistler’s Mother”-inspired series she and her daughter created. But the wonderfully wry images live on.

“We had so much fun doing it together, and I like to think of her traveling the world, as the series has been such a success and has been shown in Russia, China, Korea, Italy, Spain, Australia, and the United States,” says Smithson. “She would have loved that.”

Robert Kiener is a writer in Vermont.

View Gallery

View Gallery