Mark Edward Harris name-drops a lot. The Los Angeles-based travel and documentary photographer’s casual mentions of friends would fill a photographer hall of fame: Alfred Eisenstaedt, Mary Ellen Mark, Annie Leibovitz, Gordon Parks, Joe Rosenthal, Helmut Newton, Marc Riboud, Peter Lindbergh, Herb Ritts, Sebastiao Salgado.

He’s not showing off. These teachers, as he calls them, make up half of the 20 subjects he interviewed and photographed for his 1998 book, “Faces of the Twentieth Century: Master Photographers and Their Work.” In addition to giving him access to photography’s greatest legends, the book proved a career-shifting enterprise, launching Harris into long-form photography and essays. He’s now published 10 photography books and been published in Vanity Fair, The New York Times, Life, Time, Newsweek, Geo, and major travel magazines.

The book also made a name for him—literally, not just in the prizes it won or its translation into German and French. “Up until 1998, I was always Mark Harris,” he says. Deciding that it was a boring name for an author, he added his middle name to his professional moniker, and he’s been Mark Edward Harris ever since. “It’s probably one of the only branding decisions I’ve ever made.”

By any name, Harris built his brand of unique images of familiar spaces and intriguing images of unfamiliar places via continuous process improvement. He soaks in the proficiencies of those who’ve come before. “I’m definitely gleaning consciously or subconsciously so much knowledge about approach and the photography medium,” he says, citing, for example, Andreas Feininger’s attention to technical detail. Harris expands on that knowledge with constant study, experimentation, and practice to ensure he captures every image with the best possible exposure, lighting, and timing.

“I’m most fortunate,” he says of his career path, then adds, “I don’t use the word ‘lucky’ because I consider luck just pure chance.” That points to his no-excuses approach to photography. “When you’re shooting professionally, you can never come back with, ‘I didn’t get it because ...’” Harris says. “Whatever is after that ellipsis doesn’t matter. You can’t publish an excuse.”

“It was not a set-up environmental portrait, but I did prevision this stylish officer directing traffic,” Harris says of one of his favorite images, a North Korean traffic officer at work.

His photograph of Petra’s Treasury, one of the most elaborate temples of that ancient city, exemplifies this mindset. Seeking a unique angle to portray one of the world’s most iconic structures, Harris noticed people climbing on the rocks to one side of the plaza. “Not sure you’re supposed to be there,” he says, but he went up there himself, set up his tripod framing the Treasury between two outcroppings, and set his camera for a long exposure to get the movement blur of people below. He started shooting, then noticed out of the corner of his eye a boy on the rocks to the left of him. Harris wondered how the kid got there, triggering the realization the boy had only one way out: jumping across the chasm Harris was using to frame his image. “I recalibrated: I’ve got to get to a higher ISO, I’ve got to get to a faster shutter speed, prefocus on the area where he might land, put on the motor drive. This is happening in a fraction of a second, and sure enough, this kid jumps.” The boy leaping through the air against the Petra Treasury backdrop ended up on magazine covers.

“Got to get the shot, that’s the bottom line. Simple as that,” Harris says. He also relies on a Zen attitude. “If you let the superego get too involved and filter stuff instead of just reacting to things, it really can get in the way of creativity. That said, you’ve got to have the technical skills to act upon those moments. All photographers who are really in the moment have emptied their brain and let everything they’ve learned flow through them.”

RESPECT IS EVERYTHING

Speaking via Zoom, Harris is in Tokyo to lead a photography workshop. The curriculum is indicative of Harris’ devotion to looking beyond a country’s landscape into its singular culture. The students, many visiting Japan for the first time, will do typical touristy things such as visit the Golden Pavilion, the Meiji Shrine, and Mount Fuji (photographing from the east side to get the morning light). They also will photograph an authentic tea ceremony, kyudu (the Japanese martial art of archery), geishas, and snow monkeys. Harris has visited 106 countries, including North Korea 10 times, but Japan is his heart’s home. He speaks Japanese conversationally, and among his books, 2003’s “The Way of the Japanese Bath,” now in its third edition, is his favorite.

The week before our conversation Harris was in Kharkiv, Ukraine, photographing a bombed zoo’s surviving residents and visited another animal rescue mission a mile from the Russian border. A common thread throughout his work is what he calls his humanistic approach to photography, and respect is his most important skill set. “How can you shoot a respectful photo if you’re being disrespectful?” he says. “When I photograph in North Korea or Iran or Iraq or wherever, I genuinely like the people. I’ve been in places where bad things happen, but overall people are good and want to help their fellow creatures and fellow humans. I try not to treat people like objects.”

The same holds true for his attitude toward animals. His orangutan images, photographed at zoos in Singapore, Tokyo, Indianapolis, Indiana, and Wauchula, Florida, and a rescue center in Borneo, are remarkable for their portraiture quality. Harris used a strobe to overpower ambient light and a variety of stops and differentials to create a black background, making these great apes look like authors, theater actors, and statesmen. Humans and orangutans are two of the five great apes, Harris points out. “We share a lot of DNA, and you really do get from orangutans in those portraits similar looks that you see in humans. But I’m not trying to make them look human any more than I’m trying to make humans look like orangutans.” An Indianapolis Zoo orangutan even gestured a request to see himself on the LCD screen. “He didn’t ask to sign off on the shot, he didn’t give a thumbs up or a thumbs down, but he ended up on the cover of my book,” Harris says.

For portraits of a Wisconsin rescue shelter’s dogs, Harris developed a slightly different lighting technique. “Orangutans have fairly flat faces, so I was able to do a raking light from an angle. Because dogs have snouts, I used a beauty dish straight on. If you have a dog with a long snout and you light from the side, it throws too much of a shadow.” He tested on a stuffed animal at his L.A. home. “When you’re on location doing an assignment, that’s not the first time to do a test.”

TELLING A STORY

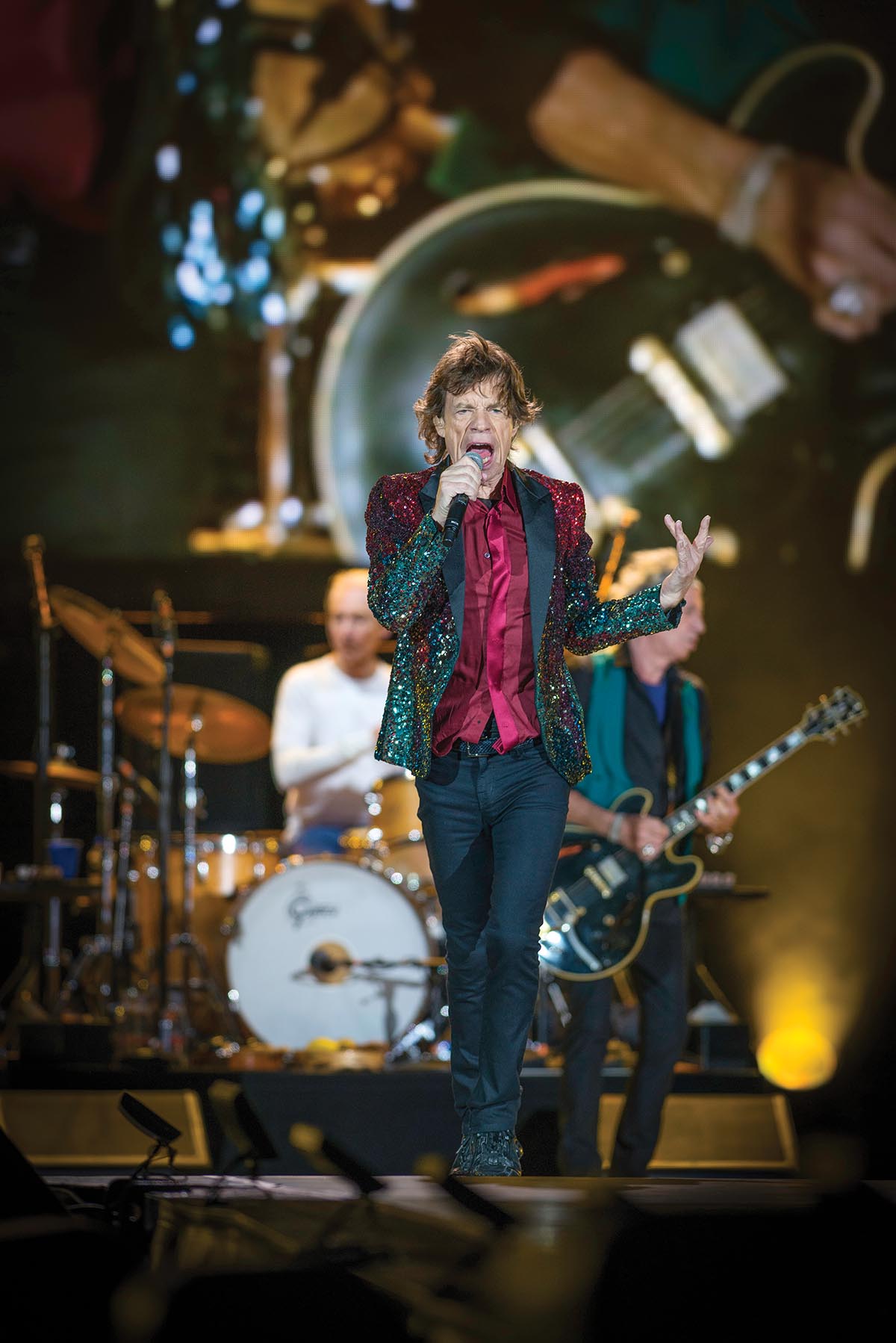

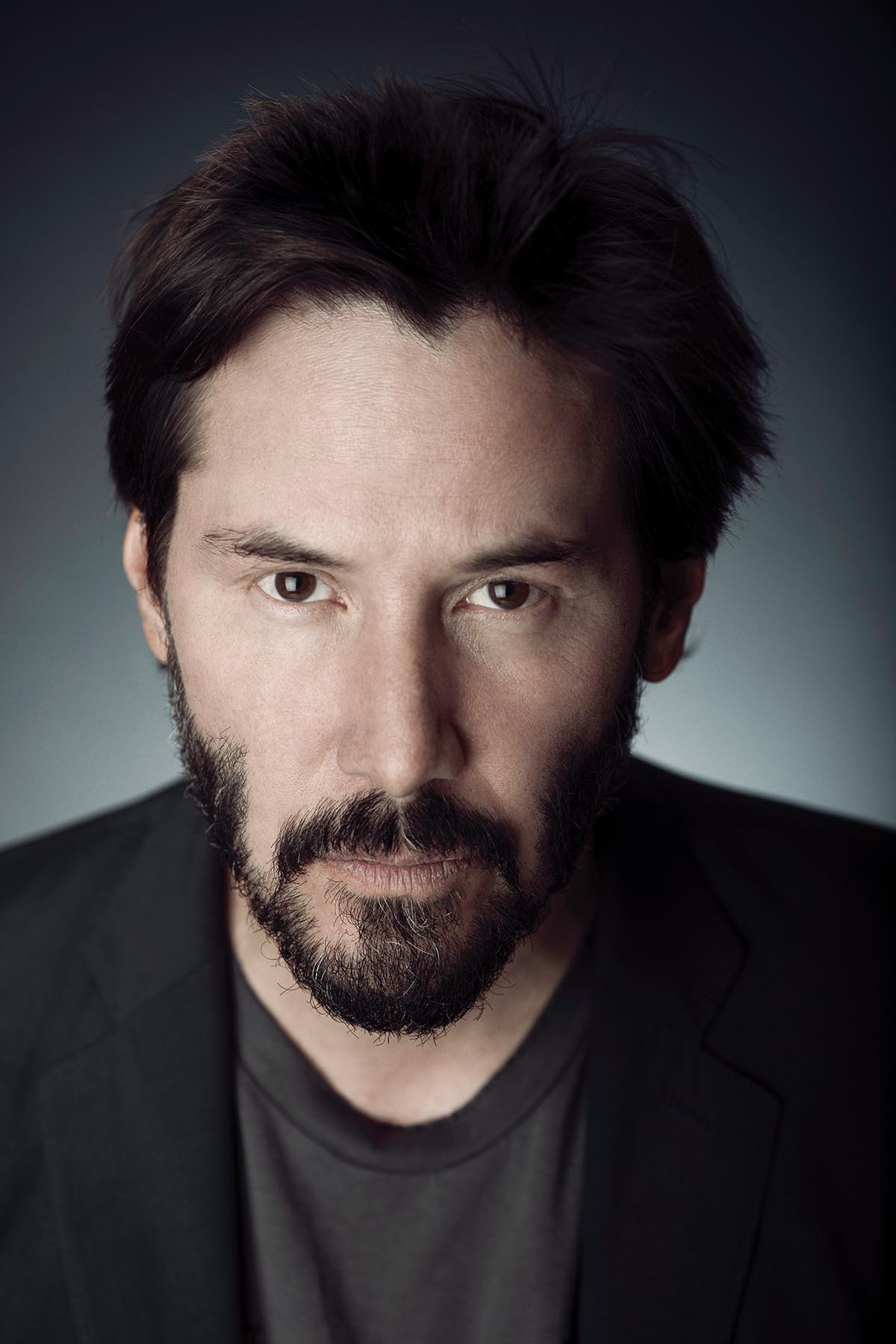

His photography mines every genre except one: “I’m not a car photographer,” he demurs. Yet, he suggests that photographers should find their own niche. His niche is not in style but presentation, using a long-form approach even in his social media postings. “I will not do one shot of an animal and then one shot of a North Korean soldier and the next one of Mount Fuji, and then all of a sudden you have a picture of Keanu Reeves.” On social media, he posts images from one series before moving to another set, even forestalling posts of his newest images. His website is divided into titled sections such as “The People of the Forest” (orangutan portraits), “Call of the Wild” (wildlife), “Wanderlust” (artistic travel photography), “Naked Hollywood” (the city’s street life). This way, viewers—especially prospective art directors and buyers—focus on his storytelling strengths instead of a swath of disconnected, albeit brilliant, images. He even divides his Japan images into stylistic topics: baths, Olympic Games, and the tsunami, are, respectively, artistic black-and-whites, action sports, and heart-rending photojournalism. “For clarity of presentation, there always has to be a hook, and there’s always got to be a reason,” he says.

He also pursues assignments by focusing on narrow narratives. “You can’t just say, I’m going to do a story on Paris; it’s too broad. Just like you have to polish rice for a good sake, you cull all the time. In terms of story development, you’re culling, you’re digging deeper and deeper and deeper in.” This is photojournalist Eve Arnold’s influence; she created her own photo essays rather than waiting for the phone to ring. Harris offers his Japanese baths series as his perfect example. He loves Michael Kenna’s black-and-white Japanese landscapes and lauds Jodi Cobb’s photojournalist series on geishas. Harris, therefore, produced black-and-white artistry by immersing himself in the baths culture. “I was a participant as much as documenting it,” Harris says.

JOURNEY TO ARTISTRY

Born in New York and raised in San Francisco, Harris was influenced by his father, both by the photography he did for his public relations job with KCBS Radio and his passion for photographing family trips. “My love of travel definitely came out of those family trips,” says Harris, who assisted his father in these photographic travelogues. In his third year at California State University, Northridge, Harris had his first darkroom experience of seeing an image emerge on paper. “That’s when I lost myself in photography,” he says. His love of the darkroom helped shape his skills. “Trying to rescue a poorly exposed negative really taught me how to make a proper exposure.” He earned a master of arts degree in pictorial/documentary history at California State University, Los Angeles, then took a job as green room host for “The Merv Griffin Show,” where he also photographed stills on the set. When the show ended its run, Harris traveled through Asia for four months building a travel portfolio.

Then his career backtracked—intentionally. “I realized I didn’t have all the technological skills that I wanted to know,” Harris says, so he worked as a photographer’s assistant, including Playboy magazine sessions. “It was like product photography with people,” he says, working with 8x10 cameras, a wide array of lighting equipment, huge sets, and models posed and lit to look perfect without post-production. “Very carefully constructed in terms of lighting and body positions,” Harris says. “Those years assisting had a huge influence on me,” including a get-it-right-in-the-frame ethos. Today, he limits his post-production to what he could have done in a darkroom, “some burning and dodging.”

Don’t mistake this for avoiding what’s new. When Harris gets a new camera, he downloads its online manual. The full manual for his current Nikon Z 9 is 914 pages, which Harris printed out to carry with him in a three-ring binder. He read every page and admits he didn’t understand it all, so he turned to his other ready source of knowledge: his self-described teachers. Photographing the Beijing Olympic Games as his first assignment using a mirrorless camera, Harris asked Nick Ut for advice. “He said go shoot hummingbirds. It was a brilliant idea. You need fast shutter speeds doing sports, and who’s faster than a hummingbird? And I really got to understand 3D tracking. The success of my work in China wouldn’t have happened if Nick Ut didn’t say go shoot hummingbirds.”

That’s Harris’s go-to formula for success: homework, practice, and soliciting advice from a Pulitzer Prize-winning peer.

Eric Minton is a writer and editor in Washington, D.C.

View Gallery

View Gallery