The hand reaches across the image, palm up, fingers beckoning. It looks like it’s reaching in supplication, for food, maybe, or, just as likely, connection. With long fingers, boney arm, and skin covered in bristly fur, it is the arm of a white-bearded gibbon in Borneo and perfectly represents wildlife photographer Kristi Odom’s life mission.

The image’s power is in what it is and what it seems to be. “It’s an endangered gibbon with its arm out,” Odom says, “and that arm out makes me think it’s asking for help, asking for the story to be told. It’s a nice one to pull people in.” Which the image has been doing for almost 20 years. One of Odom’s earliest award-winning wildlife pictures, it has been displayed at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History and occupies a central place on her website home page. When she took it, she was a wedding photographer.

EMOTIONAL CONNECTION

Labeling herself a visual artist, Odom tells Earth’s stories through photography and workshops. Her images are visually powerful pieces of art, and some accompany her articles published in The Washington Post and online for National Geographic. Odom’s seminars and destination photography workshops promote conservation while providing one-on-one photography tips. “It is my mission to connect people emotionally to wildlife through visual art and wildlife adventures. I want people to experience the personalities and emotions of animals,” Odom states on her website.

But not in anthropomorphic ways. “Animals have their own emotions; they don’t have the same emotions as us,” she says in a Zoom call from her home in Longmont, Colorado. “Animals don’t have the facial expressions, the tears, and the smiling that we have, so I think there’s a lot of power to gestures and touch and things like that.” Similar to the gibbon’s arm, many of Odom’s wildlife images are closeups: a bear cub’s head looking back over its shoulder against the backdrop of its mother’s furry back; an elephant’s trunk curling around its tusks; a dragonfly’s back; an orangutan’s hand slapped over the back of its shoulder.

Odom doesn’t go into the wild seeking preconceived compositions. “It’s more a case of opening my eyes to see and to feel. And the animals give us their personalities if we watch close enough and study them close enough.” For every photo, she asks herself three questions: What do I see? What do I feel? What can I eliminate? She sees a gibbon threatened with extinction; she feels a connection to the outstretched arm; she frames the arm tight with a minimum depth of field. The emotions she’s portraying may be her own, but that still serves her purpose to tell the species’ story of losing habitat to global warming, falling into traffickers’ hands, or otherwise suffering from a homocentric worldview.

“Photographing how I’m feeling is important to being an individual and an artist in the industry,” she says, and tells of the first time she photographed sharks. Frightened when she went into the water, “The first thing I saw was simplicity and peace.” So, she shot silhouettes to focus on the sharks’ simple forms.

WEDDINGS OPENED THE DOOR

Odom marketed herself as a destination wedding photographer to pay her way to nature photography in exotic places: She visited Borneo while working a wedding in Thailand. “So many people for so long told me I needed to specify, to find one genre and stick with it,” she says. “I find that to not be the best advice.” Weddings helped her understand the power in photographing emotion. “And then the wildlife photography showed me a nontraditional way of seeing emotion, through gestures, when eyes are closed,” she says. “Animals really taught me how to watch body language.” Applying that to wedding photography earned her awards and a Nikon ambassadorship. That gave her the confidence to make wildlife photography her full-time vocation four years ago, “Which was very, very hard because wedding photography is lucrative,” she says.

It was not the first time she passed up higher earnings for a passion. Odom was a math whiz growing up in Atlanta, Georgia, and headed down an engineering career path. She was particularly close to her grandfather. “I used to be a big introvert, and he was, too. We played cards all the time together.” He enjoyed photography, and she started seeing his life, travels, passions, and love of family through his photos. Noticing her interest in his photography, he left the 15-year-old Odom his camera along with his Georgia Tech class ring when he passed away.

The ring may have represented what seemed her predestined path—she received a full electrical engineering scholarship to Georgia Tech to specialize in photovoltaics—but when she pulled out her grandfather’s camera, she realized she could hide behind it and still be at the party. She also found her voice, “And the voice was coming through in the photography,” she says. “I could share experiences, and it started bringing me out of my shell.” She began photographing college sports and covered concerts for RollingStone.com. It was a concert that, on her 21st birthday, diverted her from a high-salary engineering career to clambering over mountain rocks photographing Micky Mouse-eared pikas.

BLAME BONO

“I blame Bono,” she says, but it has nothing to do with the U2 front man’s save-the-planet ways. Odom was in the camera pit when U2 began playing “Beautiful Day” and Bono sang it to her, his face so close to her lens the resulting image represents him as a barely discernible blur. “It was one of those moments where I was shaking with excitement, thinking, if photography can take me here, imagine where I could go,” she says. “It was really hard to get into my electrical engineering classes the next day.” That moment alone convinced Odom to pursue a photography career instead of photovoltaics, but she also took the song’s lyrics as a pointed message: “It’s a beautiful day, don’t let it get away.” “In a lot of ways that relates to photography and the fact that we do get to keep all these beautiful moments.”

Upon concluding her junior year at Georgia Tech, Odom transferred to the University of South Wales in Sidney, Australia, to earn a degree in fine arts with a concentration in photomedia. Transitioning from a math-based, logic-centric curriculum to creative thinking was hard. “I almost failed out of fine arts, and I was used to having high honors,” she says. “It took me a really long time to think creatively and express myself and who am I and what I wanted people to see in my work.” Still photographing concerts for Rolling Stone, she knew the technical aspects of lighting and photography, just not how to put emotion into her self-assigned work.

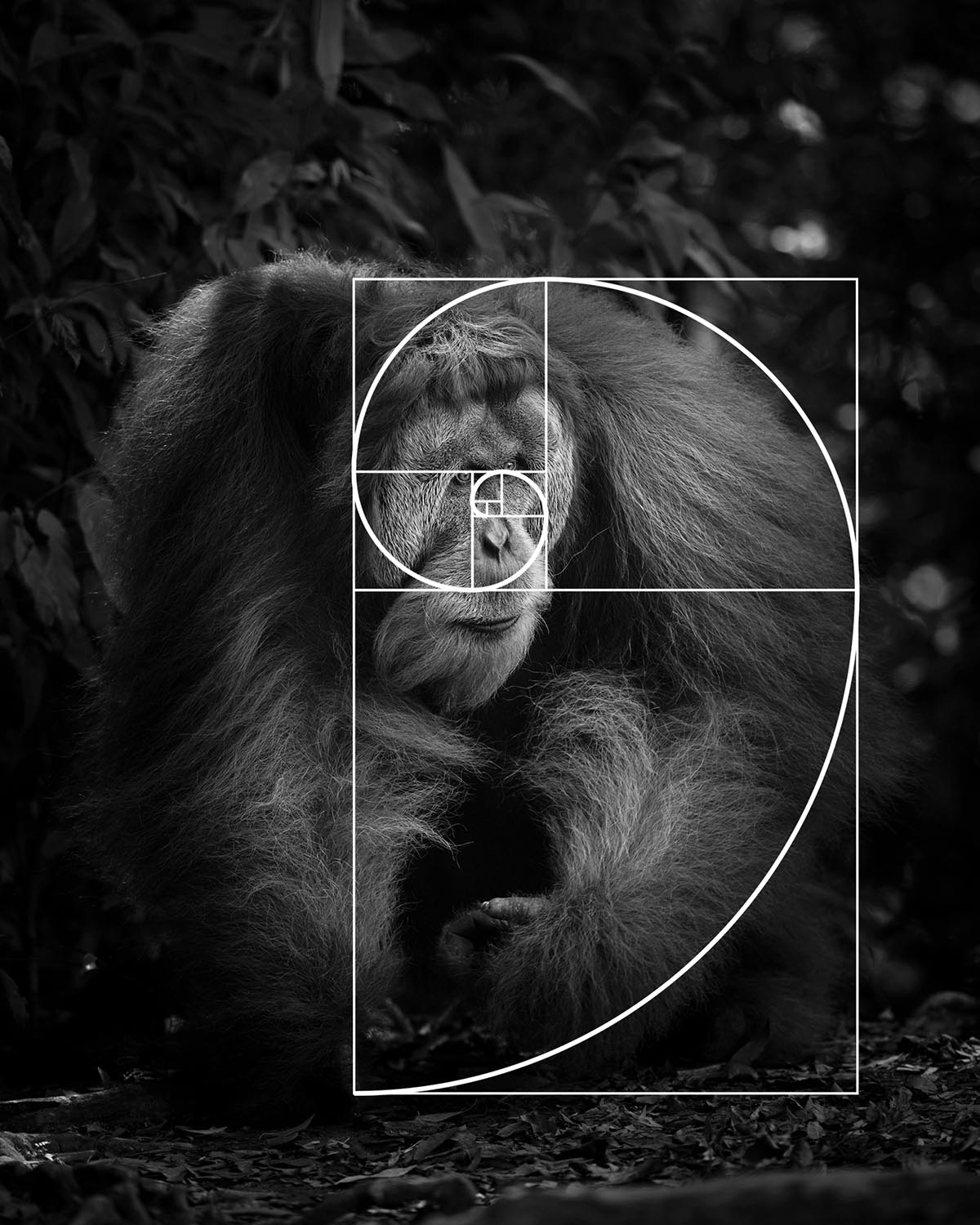

And then, math provided her artistic breakthrough when a teacher showed her how to use lines and geometrical shapes to lead eye movement in an image’s composition. Her wildlife images rely on triangles, circles, squares, and diamonds in their composition, as well as her favorite mathematical sequence, the Fibonacci spiral.

A math lover, Odom uses the mathematical Fibonacci sequence, a spiraling diagram (at right), to direct the viewer's eye.

A FOUND PATH

Despite her mathematical bearings, Odom loves embracing randomness, she says. “I think a lot of times our paths find us.” Such as the time she traveled to Ecuador to participate in a seminar, tested positive for COVID-19, and quarantined eight days in a hotel room reading tourism brochures. A doctor cleared her two days before her flight, so though Odom missed the seminar, she was able to visit one of the lodges advertising its hummingbirds. “When I saw the hummingbird over my shoulder, it was the most amazing moment of sheer beauty,” she says.

She next attended a conference in Las Vegas, where Nikon asked if she had an idea for a campaign promoting its new Nikkor Z 400mm f/2.8 TC mirrorless lens. “I said, hummingbirds, Ecuador.” A couple weeks later, she was back in Ecuador for a “Birds of Ecuador” video, which Nikon recently released. She’s scheduled one of her 2023 workshops for Ecuador. “It’s funny that things that might be misfortune, if we look at it the right way, open doors in different directions.”

In that workshop, she not only will be able to experience the birds of Ecuador once again, she will also live vicariously through her students as they experience them for the first time. “I love sharing passion for photography, for the planet, for wildlife, and I love teaching,” she says. “I really want to teach more people to tell nature stories, I want to teach them how to be a better storyteller, I want to teach them how to be a better photographer, and I want to give them life-changing experiences at the same time.” She believes mentoring other photographers to advocate for biodiversity in their own communities is just as effective as publishing her own photo stories in National Geographic.

Like her photos, her mission is suffused with infectious passion. “A lot of it is just looking at wildlife and the planet,” she says. “That feeling of being small because we’re in a place so big. And we share this world with so many amazing species and emotional beings that are not humans. I’m constantly inspired by wanting people to feel what I feel in nature, which is the sublime.”

Eric Minton is a writer and editor in Washington, D.C.

Tags: wildlife photography

View Gallery

View Gallery