Malinda Julien’s two-pronged photography studio

Melinda Julien's photography studio has two divisions—one dedicated to dog show photography and one dedicated to food and architecture photography.

• December 2018 issue

"It’s kind of an odd combination,” admits Malinda Julien, CPP. Her Fort Worth, Texas, photography business has two divisions: one dedicated to high-volume dog show photography and another to commercial and editorial work with a focus on food and architecture.

“Twenty-five percent of our business is from the dog show world,” Julien explains, which earns the family-run company a whopping $250,000 a year. Since dog shows are contracted for five years, that’s known income she can count on—a great complement to the food and architecture side of the business, she says, because “It gives us the freedom to say which job we want to do and which ones we don’t want to do. So we can be picky with clientele.”

It also allows the studio, where her husband, two sons, and a daughter-in-law also work, to take on altruistic projects. At the local Food Bank, she’s trained chefs in food styling and handled the organization’s photography at no cost, for example. “We do a lot of pro bono work for nonprofits—about $60,000 a year. We really want to give back. But if we didn’t have those [dog show] events that are so far diversified from what we normally do, we couldn’t dedicate that much time to our community and would have to take on more clients because we’d need the money coming in. That diversification has really paid off for us.”

A business model that works

Julien came into dog show photography organically. “I have been showing dogs since I was 8 years old,” she says. Twenty-plus years ago, her European-bred shepherd picked up a win, and she asked the official dog show photographer for a win photo. As she leaned over to position her dog for the photo, she saw the flash go off. “I said, ‘Excuse me, I wasn’t ready,’” she explains. “And the guy just looked at me and said, ‘That is as good as it’s going to get,’ and walked off. I was almost in tears.” Adding insult to injury, the photographer sent her a bill with two photos she didn’t want to purchase. “I paid him but vowed that that would not be the last time he would see my name. We’ve taken 90 percent of his contracts inside the state of Texas, which is a hotbed for this sport.”

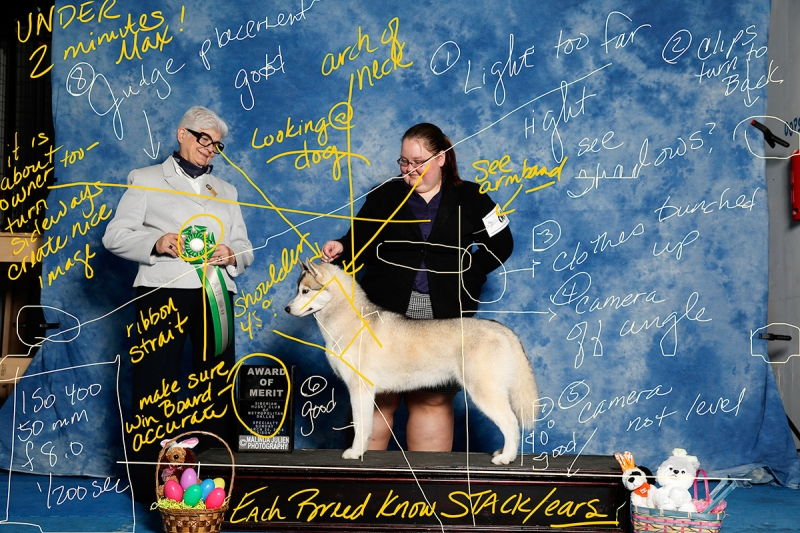

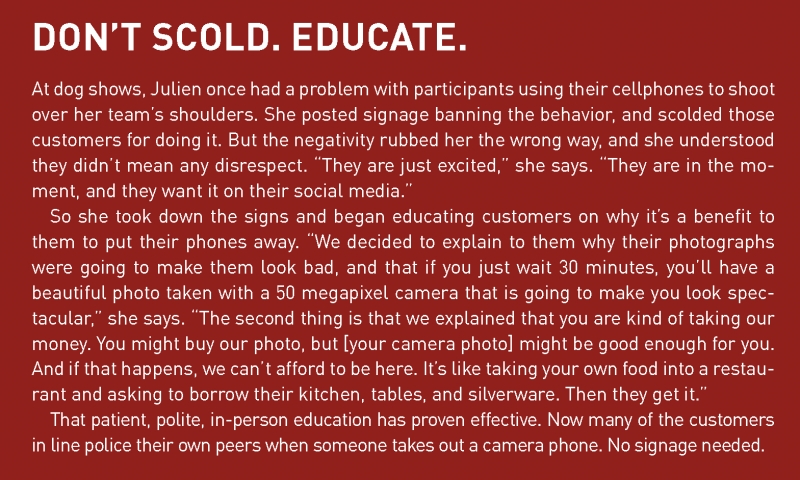

At the largest dog shows, Julien and her team may see as many as 4,000 dogs a day over five days, working 14-hour days. “It gets nuts,” she admits. But over the years, they’ve perfected their workflow, with laser focus on the customer experience. “We’ve basically revolutionized how dog show photography is done,” she says. “It’s all customer-driven.” Unlike the dog show photographer who made her official photograph, she doesn’t charge a sitting fee; customers make purchases only when they want to. And customer service is paramount. “We swore that nobody, no matter how small their win or how big their win would ever be treated any differently,” she says. “When you are on my podium, in front my camera, you are the most important person, and that dog is the most important dog.”

With the rise of social media, participants are more anxious than ever to get their hands on a sharable image quickly. In response, Julien and her team have refined their workflow and upped the ante on equipment to make sure each customer receives quality, edited digital images within 30 minutes.

“It’s really a big production,” she says. “We take three full light studios and custom backgrounds for all the different shows. We have two tech people in the back with computers that are constantly pulling all the images in from all the cameras that are shooting. Sometimes we are serving 23 rings at a time.” After the images are organized, color corrected, and edited in the back room, they’re accessible via iPad by personnel manning the studio’s customer service area. After standing for an official photograph, customers are advised to visit the customer service area to place orders. They also have real-time access to their photos on the website, so if they prefer to skip the in-person sales experience, they can download digital files and make print purchases online. The goal is to meet customers’ needs as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Operating this workflow has meant a $40,000 investment in equipment, most of it Apple: Mac laptops for culling and editing, iPhones for taking mobile payments, mini iPads with Square for credit card payments, iPads for in-person sales in the customer service area, and even Apple watches for correspondence with camera personnel in the field. The team brings duplicates of each piece of equipment to shows in case something fails. “It’s taken us a number of years to get the workflow down,” she says. “We used to have 20 people at a show and now we can do a very large show with five or six people.”

Room for food

With her lucrative dog show work scheduled years in advance and taking up intense but short bursts of time, Julien has plenty of resources to devote to one of her greatest passions, food photography, which she’ll speak about at Imaging USA 2019 in Atlanta. “I thought I wanted to be a chef at one point. So it’s not just about food but professional-based food,” she says. “It was the plating—the plating. Just to look at the beautiful colors and shapes. I’m drawn to food photography because of its graphical nature.”

Julien does between 30 to 50 food projects a year, both commercial and editorial—enough to stoke her creativity without stretching resources too thin. Her dog show work is so demanding that the drama of a magazine shoot is nothing. “We can handle anything a magazine throws at us. If they say we have to have this done in two hours, piece of cake. We can handle people who are stressed. That takes a lot of training and skills.”

Based on her food photography expertise, Julien offers the following advice:

Seek jobs where you dine. If Julien notices a restaurant’s menu photography isn’t up to snuff, she leaves her card with the manager, offering to reshoot the business’s dishes. “We pick up clients that way all the time,” she says.

Educate the chefs politely. When she needs to plate food differently than a chef has arranged it, Julien patiently walks them through the technical aspects of her alterations, always photographing tethered so she can immediately show them the results. After they understand her methods, they typically relax.

Think of food as a person. Food photography isn’t unlike portrait photography, says Julien. Beans and cornbread: What does that make you think of? “Your grandmother,” Julien says. “You wouldn’t put that on a serious gold plate.” How does the food make you feel? What emotion do you want to convey? Let those questions guide your styling. “Is your food light and cheery like a child? You may want to play with color. Is it something that’s really graphical, like styled cubes of food? Then I’m going to do a top-down [angle].”

Mind the angles. “This is where the mistakes are,” says Julien. Novice food photographers often want to go with the wrong angles. Generally you want one of three: a top-down angle for a graphic feel, a point-of-view angle to show how it will look to a diner seated at a table, or a macro angle—straight into the juiciness of the dish.

Bring your own lighting. “I always bring everything; I want to control every bit of that,” says Julien. While she likes window light, she doesn’t advise relying on natural light in a restaurant, as it will change every five seconds. If she wants a window light look, she replicates it with her own lighting.

Channel your OCD. When you sit down to eat a bowl of fruit, you won’t notice a small bruise on the apple skin or whether a strawberry’s seeds are perfectly spaced. But you’ll see every food imperfection in a photograph. Veggies should look fresh and dewy, so keep them moist. Hot foods should be steaming. Julien may spend a week searching for the perfect ingredients for a session—the hero strawberry, the perfectly gridded waffle. “For one dish, you may spend 4 to 5 hours doing it. It’s not for the person who likes to spray and pray.”

Plate it right. That means putting food toward the front of the plate, and not using a huge plate.

Scale prices and services to the client. Three things to consider in setting prices: How much is your overhead? How long is it going to take? What are they going to use the photos for? “Let’s say I have a mom-and-pop food truck down the street. They’re not a five-star restaurant downtown. They need some pictures for the outside of the food truck and for social media. Their overhead is high compared to what they make. We understand the restaurant business. And we know they don’t have $12,000. They might have $1,500.” So she scales her services to meet their needs at that price. For example, for $1,500, she might photograph three versions of two dishes in two to three hours. For a large chain or a five-star restaurant, she scales up, taking into account the need to have the photography done in the restaurant and the high degree of styling that will require hours of work for each dish.

Price for your skill level. Raise your prices as your experience as a food photographer deepens. “Pricing can be a death sentence if you are too high or too low. If you are too busy, you are too low.”

Regardless of whether she’s working with commercial, editorial, or dog show clients, Julien says there’s one overarching concern: Customer care is foundational to her business. “Every company, every person, every dog, every plate of food, every architect, every realtor is that important, and that is why we are successful,” she says. “I am not the greatest photographer in the world. I am a good photographer. But we care about our clients and we built our entire company around that concept.” And that has made all the difference.

Amanda Arnold is associate editor of Professional Photographer.

View Gallery

View Gallery