Linking People to Nature

Gabby Salazar on the power of storytelling in conservation photography.

• April 2021 issue

Can an image inspire someone to donate to an environmental cause? And if so, what kind of image—or series of images—motivates them to follow through on that impulse?

These questions are central to Gabby Salazar’s career as a conservation photographer. Over the past decade, she’s traveled the world documenting conservation work—for example, efforts to bring back birds from the brink of extinction on the island of Mauritius. But what purpose do her images serve if not to raise awareness and persuade the public to donate time and money to these causes?

“It’s really important to think critically about the visuals we use when we communicate about these big issues,” she says. Research shows that people process images more quickly than they process text. They also remember images more than the written word. “So it’s really important to think about what we are communicating and why we are communicating it.”

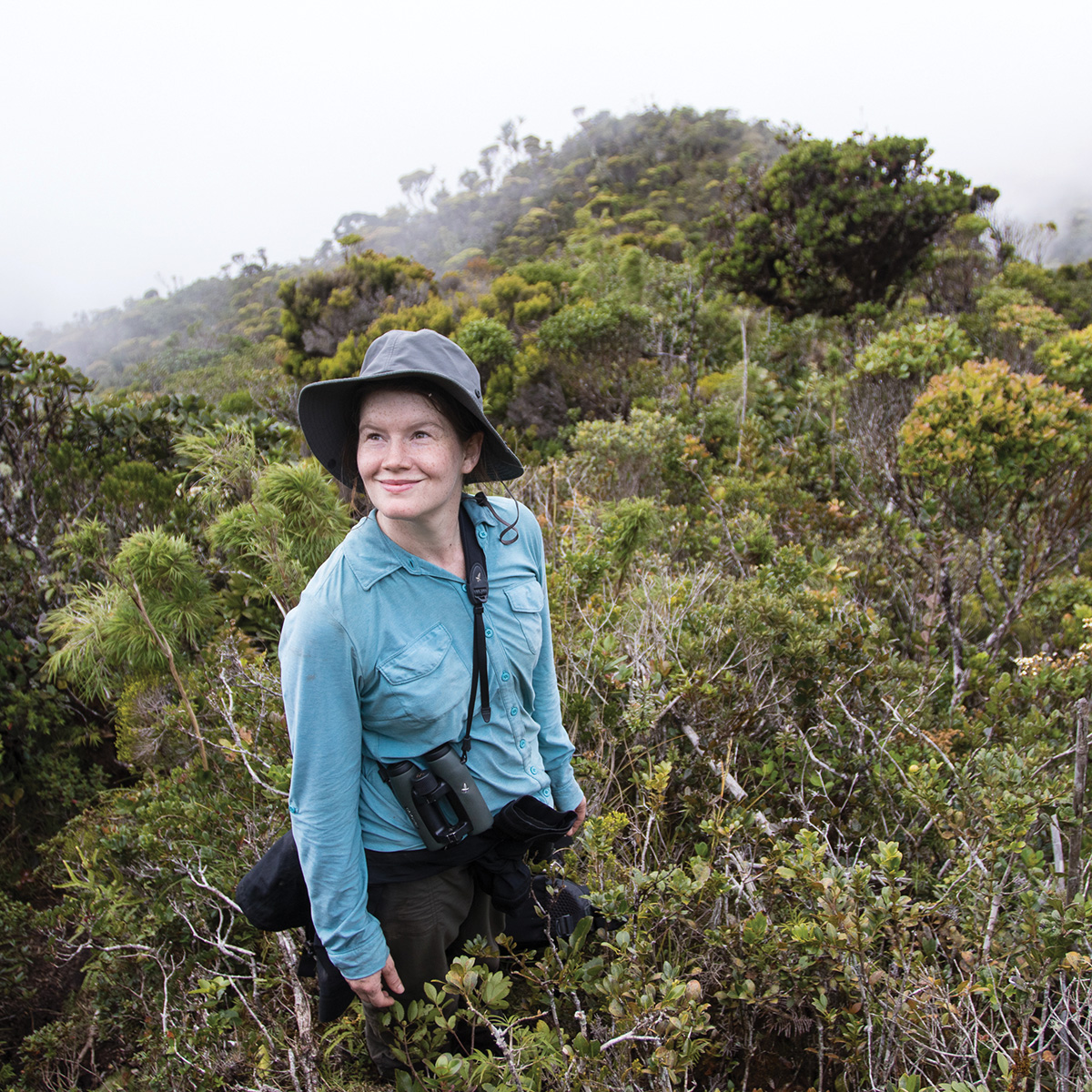

Conservation photographer Gabby Salazar

Conservation Photographer in the Making

Salazar’s photography journey began at 11 years old, when her amateur photographer father took her to a friend’s backyard bird garden to make images with a long lens. “I was just completely hooked the minute I saw a bird through the lens and I could see the details in the feathers and the glint in the eye,” she says. Her hobby blossomed and soon brought her international recognition; at 16 she won the BBC Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year award and traveled to England to see her work displayed at the London Natural History Museum.

In college at Brown University, Salazar studied science and technology with a focus on the environment and society. “I was always interested in how you influence people’s perceptions and attitudes and understand their relationship with the environment,” she says. “That grew out of my interest in photography because I saw how people reacted to my images when I had exhibits or shared them in presentations. I noticed that people were not paying close attention to nature in the way I was. And I was interested in media’s role and scientists’ role and photographers’ role in bridging that gap between people and nature.”

Conveying the Whole Story

Since college, 33-year-old Salazar has advanced her studies on the impact of environmental imagery. She completed a master’s degree in conservation science at Imperial College London and is now working toward a doctorate at the University of Florida, where she’s studying people’s perceptions of environmental images and the impact of images on support for biodiversity conservation. She’s also part of the International League of Conservation Photography, a group of more than 100 photographers worldwide who document environmental problems and solutions.

What sets conservation photography apart from wildlife or landscape photography, explains Salazar, is its mission-driven focus on a narrative, or series of images, that tells the whole story of an environmental issue. “Often it’s more about storytelling and less about a single image or artistic expression.” When she documents a project—for example, scientists working to save an endangered parrot on an island—Salazar addresses all the issues surrounding the problem and its solution. In this case, her photography would tell the story of the pet owners who keep the endangered parrots, the parrots as they are in the wild, the habitat the parrots need to survive, the threats to the parrot’s livelihood and existence, the pet parrot trade, the scientists who study the parrot, and any conservation efforts toward saving the bird. “It’s a whole suite of images that try to visually show the whole story of why the parrot is endangered, what is being done to help it, and what could be done to help it,” she says.

Salazar notes that in her line of work, applying for and receiving grants is essential, as is making in-kind arrangements with organizations for housing, often in exchange for access to images or help with storytelling.

But her role doesn’t stop with the click of the shutter. “It’s about where the images go and the power they have,” she says. Typically, it falls on the photographer to get the images out to the public, whether that’s through local or international media or through exhibitions at schools, libraries, and museums. “As a journalist, you know how to make those connections,” she says, how to curate an exhibition, how to pitch a story to a magazine. “So that is part of being a conservation photographer.”

It’s great to know from the outset the main audience for the imagery. “I start brainstorming from day one where the images are going to go,” she says. “For instance, for one project I did in Peru I knew one of the main outputs was going to be a photo exhibition that was going to be in multiple locations. That helps inform what types of images I’m going to take, what types of images I need to tell the story. And I think it really helps to have a goal for the project.”

Funding and Leads

Most of Salazar’s conservation photography is grant funded; she’s had projects funded by the National Geographic Society and other private foundations, and she was a recipient of a Fulbright scholarship. Seeking funding is a huge challenge. “Doing a six-month project is not something a magazine is going to pay you to do,” she says. “They’re going to license your images at the end. They’re not going to pay for six months of field work.” So applying for and receiving grants is essential, as is making in-kind arrangements with organizations for housing, often in exchange for access to images or help with storytelling.

“I think there are other photography jobs that are more lucrative than conservation photography, like commercial photography or portrait photography,” she laughs. Very few outlets are paying for this type of content to be produced. But most of her peers and Salazar herself do the work out of a passion for the cause, she says, “and we find ways to make it work.”

As for leads on conservation stories to photograph, she comes across them by reading conservation literature and scientific research as well as articles in the popular press. Scientists also often tip her off to interesting projects they feel deserve documentation or reach out to her to document their own work. Salazar was recently invited by a scientist to document their volcanic research on an expedition in Guatemala. Opportunities like that arise because, by attending scientific and conservation conferences and talking to people whose projects could benefit from her skills, Salazar has cultivated a network of scientists who know her expertise.

Searching for Answers

In the third year of her doctoral program, Salazar is in the midst of studying how people perceive various types of imagery and the impact that has on their environmental behavior. “I would say that there is very little research on this topic, on the impact of images, even though visuals are obviously incredibly ubiquitous in our lives,” she says. “Very little academic research has focused on which types of environmental images spark behavior change.

“One of the questions I’m really interested in and what I’m doing experiments and studies on is, Are people more motivated to donate money or time to environmental causes when they see negative images showing terrible environmental problems or when they see images of pristine, beautiful environments and animals? Perhaps it’s not one or the other. Perhaps it is a combination, which would really speak to the power of the storytelling aspect of conservation photography. Those are the things I’m studying. I don’t have all the answers yet.”

But she has enough to data to consider the way she presents her work to the public. “I am already thinking a lot about how my images make people feel because the emotions we feel influence our actions. Whether or not we feel sad or angry or peaceful or joyful, these kinds of emotions all have different implications for how we act.” This spring before giving a presentation to university students on conservation photography, she had to assess how she should frame the issues to influence her audience. Would her images make them feel so overwhelmed that they’d lack the enthusiasm to try to help? Would her images leave them feeling content that everything is being taken care of by someone else?

“Photographs have the ability to really pull at the heart strings in different ways,” she says.

“For me it’s trying to find that right formula of how much negative, how much positive, how much do we show solutions. What is that sweet spot that makes sure people get off the couch or go to the website and click ‘Donate’?”

Amanda Arnold is the associate editor of Professional Photographer.

View Gallery

View Gallery