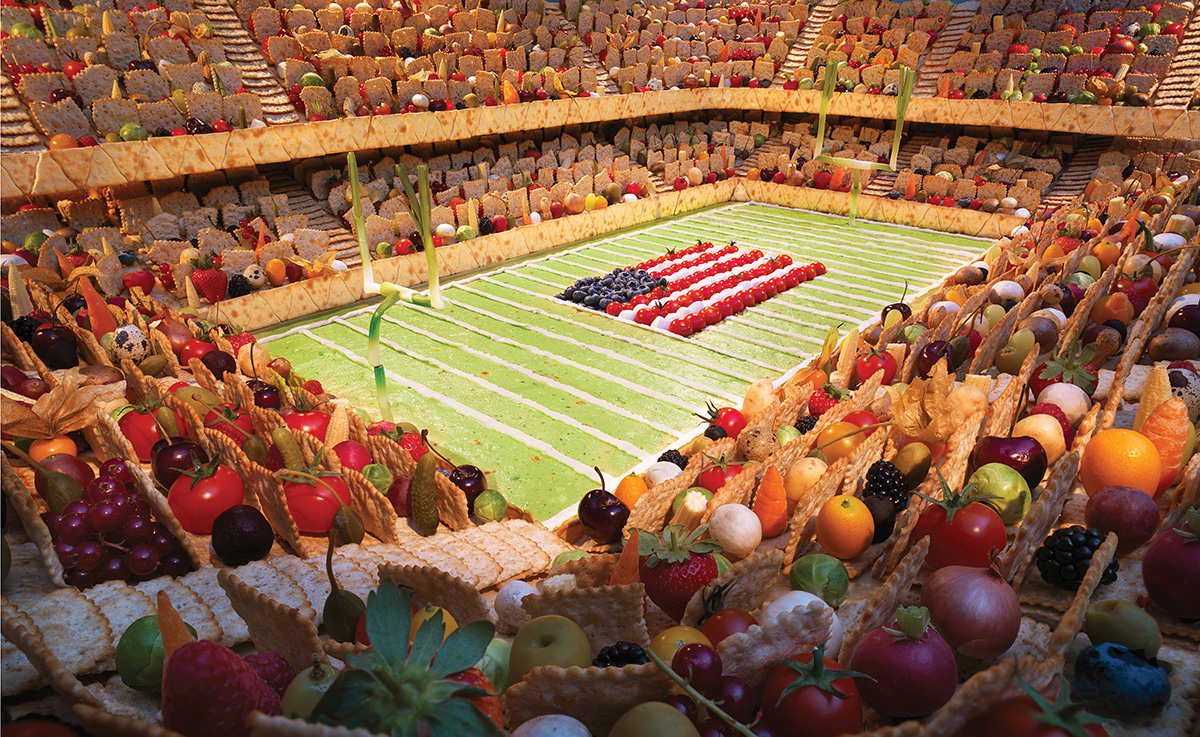

At the root of Carl Warner’s success is a visual imagination that he exercises like a fitness fanatic. It allows him to create his whimsical works: a smoked salmon sea lapping at a potato and black bread-boulder beach; a tender stem of broccoli surfing giant waves of leafy greens on a silver butter knife; vegetable noshes sitting in a Wheat Thin stadium for an American football game.

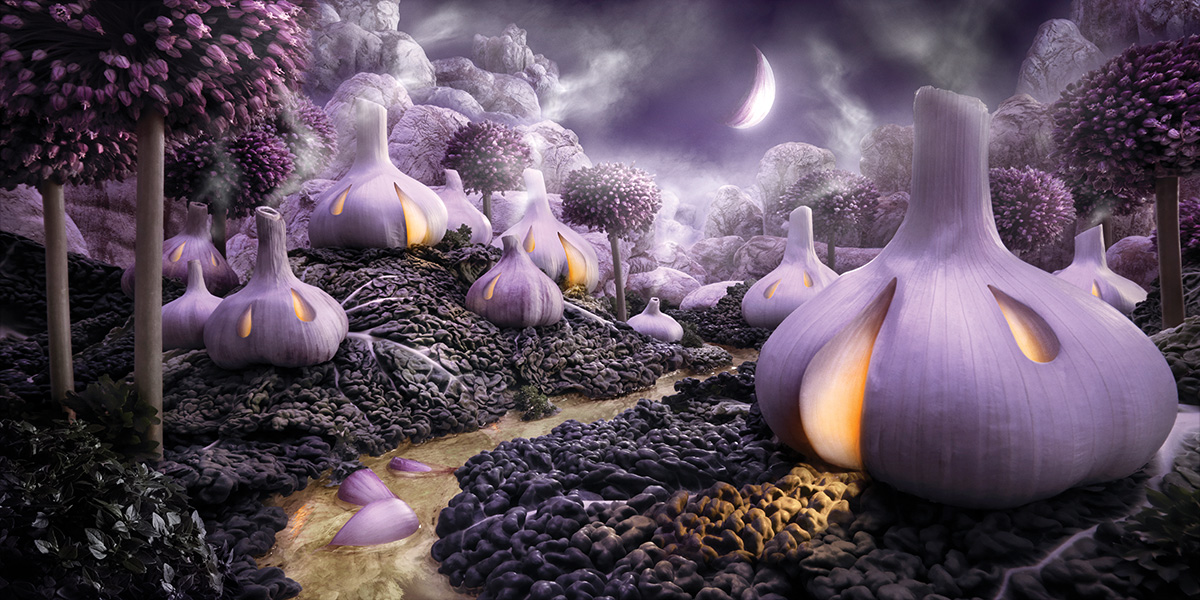

The images are still lifes: real, miniature landscapes composed of food. Warner sketches the scenes then builds them in his studio with the help of his model maker and food specialist. “Then we light the scene to make it beautiful, and the viewer says, ‘Where is this?’” he explains. He uses Adobe Photoshop only for tweaking and finessing; the images owe their impact to Warner’s diligent pursuit of making images in-camera as much as possible and his team’s handcrafting skills.

Using a Phase One iQ3 with a Schneider Kreuznach 28mm lens, Warner sets his camera at f/32 and shoots the model in stages—foreground, midground, and background—as well as sections. Helicon Focus software renders the image’s focus all the way from front to back, Warner says, so that on first looking at the photograph, a viewer will think a piece of broccoli is a tall tree in a forest of edible greens. Lighting is key. Warner uses tungsten lights to create a natural feeling of sunlight and a flash with a silk sheet over a blue lamp to provide a blue wash for the shadows. He does this while working with a model that tends to perish quickly, especially under the warm tungsten lights. “Coriander will flop in a minute,” Warner says.

He conveys why he puts so much effort into building and photographing the models by explaining why he doesn’t build scenes on a computer: “If you replicate one broccoli many times, it will look fake.” All elements of his foodscapes must “obey the laws of the lens and the lighting,” he says. He creates high dynamic range by manipulating his fill light to diligently obey the main light source of the sun or moon, depending on the food. Sunlight brings out texture and color in the ingredients, he says, “apart from fish. Warm light just makes the fish look like it is rotting,” so he uses cool blue light for fishscapes. Other than ham, smoked salmon, breads, potatoes, and a series of landscapes with baked pizzas he did for DiGiorno Pizza, Warner uses only raw ingredients. The food is his painter’s palette, “a celebration of the beauty of the ingredients,” he says. “It’s about the details and textures, not about the appreciation of food that you grab as a meal.” Rather than appetizers, his images are an immersive experience, transporting the viewer by chocolate train, peapod gondola, or ravioli balloon to locales of garlic huts at night, a cheese-and-cracker Parisian boulevard with a pretzel Eiffel Tower, or a pancake lighthouse on a berry island.

ARTIST IN THE MAKING

The homepage on Warner’s website features just eight words on a white background: “Carl Warner is an artist, director and photographer,” the three job descriptions serving as links to specific portfolios. That artist is first and photographer last is not just alphabetical happenstance. “I don’t consider myself a pure photographer. I consider myself a photographic illustrator,” he says. He admits feeling uncomfortable being featured in a magazine about professional photography. Driven by his artistic vision, he has little interest in the photographic tools he uses to do his work. “I’m not solely the photographer. It’s more than that. It’s the development of the idea, it’s the construction and all that happens before I take the picture.” That attention to detail in construction and lighting sets his foodscapes apart from imitators’.

Warner grew up an only child and spent a lot of time alone in his room. “I’d draw a lot, make things out of Legos. I had Roger Dean posters on my wall and Dali pictures. That’s how I worked my imagination, like a bodybuilder would train. I worked my imagination like a muscle, and that enabled me to work outside the box.” He studied at Maidstone College of Art in the United Kingdom to become an illustrator but acknowledges that other students were much better at drawing than he was. He found more success with photography, transferring to the London College of Printing to earn his photography degree. He recalls it as a magical time.

His dream was to be a landscape photographer, but his still-life portfolio drew attention from advertising agencies. So, he took that work and used his earnings to pay for a landscape photography trip to Iceland. “I was out of my comfort zone,” he says of the 10-day sojourn. “Landscape photographers camp out on the side of a mountain to get the early light. I’m going, no.”

But he wasn’t happy with his still-life work, either, even though his imagination, especially the way he worked with shadows, earned him consistent business. “It wasn’t bad stuff I was doing, but I knew I could do so much more, but I didn’t know what it was.”

Photographer Carl Warner builds his food landscapes with the help of a model maker and food specialist.

FAITH AND THE GROCERY

Two events influenced his eventual path, Warner says. One was parting ways with his agent in the late 1990s. “She didn’t share my self-belief,” he says. “I thought I was a better photographer and artist than I was at the time.” The other was God entering his life, turning him from a “vehement atheist to a full-on believer.” In 1999, hoping to build his portfolio between commissions, he went to the market, where his imagination saw portabella mushrooms as trees in an alien world. He began considering other ingredients for such a landscape and went back to his studio with bags of food. “My assistant asked if I was eating all this,” he says. Instead, he built and photographed what he called the “Mushroom Savannah.” At a retouching house to fix the lighting in the image, Warner says, “An art director from Finland came up to me and said, ‘Wow, I love what you’re doing here,’ and I said, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing.’”

That art director landed Warner a client who wanted a landscape of Finland’s most popular meal: salmon, dark soda bread, dill, and potatoes. Warner knew making salmon look good would be a challenge, but when he and the art director saw smoked salmon under a light “coming down on it like sunlight” at a restaurant, Warner had his “Salmon Sea” image. Next came “Broccoli Forest,” and his imagination started gushing ideas. “I never thought I could come up with as many images as we did.” Warner was thriving as a still-life landscape photographer. “It’s a journey thing. That’s a cliché, but I was on the wrong road, the signposts pointed me to the right road, but I never noticed it. When I discovered it, it was a revelation. God shined the light on it, and I went, That’s what I want to do. And I ran with it. People said, You want to do a TV commercial? I said yes. You want to exhibit? I said yes.”

In January 2008, a media company spotted the foodscapes on the internet, sold the story to The Sunday Times, and Warner’s work went viral. He became a must-get for news and talk shows. His European-centered market expanded to a global clientele. He got a publishing deal, served as a judge on food shows, was approached three times about creating a food theme park, and his former agent validated her original opinion when she told him, “I knew you had it in you.”

“It is that pop star thing where you are of interest for a short period of time,” he says. “Having said that, there are people discovering me now, a younger audience.” He’s expanded into other faux landscapes using tools, appliances, and computer equipment. He has a portfolio dedicated to human body parts called Bodyscapes. “It’s limitless,” he says. “I could take a load of COVID masks and make a snowscape. Headphones make a dinosaur. It’s only limited by your imagination.”

It’s timeless, too, “so people can rediscover it and have that wonderment from it. It has the potential to keep me going into retirement.”

Not that he’s planning to retire soon. Though COVID-19 hurt Warner’s commission work, he intends to resume his previous pace while exploring new photographic paths for his imagination. Meanwhile, to keep from going stir crazy, he took up landscape gardening.

Eric Minton is a writer and editor in Washington, D.C.