Like many newbie photographers, Kendrick Brown wasn’t planning to become a pro. He was a sports enthusiast and a shutterbug who liked capturing action photos. He’d go to sporting events held by the local YMCA and enjoy snapping a few photos.

One thing led to another as the parents of youth sports participants began requesting copies of his photos, and soon the idea for a new business began to take shape. Brown started offering commissioned sports photos on a limited basis and his reputation grew. He got requests for team and individual (T&I) portraits. When the scope of work began exceeding his capacity, he hired contractors to help. Eventually, a few weekend jobs evolved into a full-fledged business.

Today, Brown runs one of the best-known sports photography outfits in central California. He has six employees, plus seasonal and part-time help for bigger events. His company, KAPphotos, does both action and T&I photography and has developed profitable business lines for each.

Making action profitable

The key to turning a profit in sports action photography is getting money up front, says Brown. If you’re shooting on spec there’s no guarantee you’ll sell anything. Instead, require a retainer or a minimum sale in exchange for your time. Then you can add to the sale with specific print and product sales.

Kendrick charges a flat rate to capture 20 to 30 images of an athlete, guaranteeing he’ll photograph one game for that price. If parents want him to photograph more than one game, additional charges apply. Parents can buy individual prints or a customized collage, and it’s not uncommon for them to spend $300 to $400 on a single order.

Figuring profitability

When Brown is looking at a potential job, he factors in several considerations to determine potential profitability:

Distance. Travel costs to bring a photo team and gear to an event can eat into profit margins. To attend more distant events, the number of athletes and sales potential must be high.

Prep time. Brown’s team needs to be onsite and set up at least one hour before the first game. Is that feasible given the distance and other circumstances?

Staffing. Bigger usually means better when it comes to a sporting event, but Brown also has to weigh the size of the event against the cost of staff he needs to work it.

Per-child sales average. By carefully tracking his numbers, Brown knows his average sale for different types of work. Based on the number of children expected at an event, he can do some simple multiplication to estimate potential sales.

Number of athletes. Big tournaments with hundreds of players offer more sales opportunities, but Brown will cover individual games in some cases, especially if there are higher numbers of participants. Youth football typically involves 30 or more kids on each team, plus cheerleaders in many cases.

The sport. Football, baseball, lacrosse, and ice hockey are Brown’s most profitable sports. He’s found that the parental investment in equipment, league fees, tournaments, and other expenses has a direct bearing on their photography investment. Some of these sports can cost families thousands of dollars a season, so spending $300 on sports photographs is a drop in the bucket.

With all these factors considered, Brown calculates his hard expenses for travel, materials, food, and supplies. Then he figures the break-even number of kids needed to photograph. If the event or game offers more than that break-even number, it’s a go. “Once we figure out the price point per kid, then we can usually make it work,” says Brown. “If you don’t know that, then you’re just guessing, and you could end up losing money if you’re not careful.”

Getting in with sports leagues

Most leagues already have a T&I photographer, so a good way to get in is with action photography. Brown recommends calling the league administrator and getting permission to go out and photograph. Then set up a booth displaying both action and T&I images. That way, people see that you can do both kinds of photography, and if something changes with the current T&I photographer, you’re on the inside track for that contract.

“You just need someone to agree to let you come out,” says Brown. “Then once you’ve set up your booth, you’re not just selling to the team that invited you; you’re selling to the other team and anyone who’s out there. The contacts you make while on location can lead to jobs with other clubs and events.”

Teeing up the sale

Brown’s sales process is based on two fundamentals: a sense of urgency and a connection with customers. After an event, he posts images online for two weeks, which incentivizes customers to make their purchases quickly. Customers can view the images in online galleries, but they must make all purchases by phone.

“Online orders detach us from our clients,” explains Brown. “We want to connect with them. That sales call is important because we advise them about their options and help them get what they want. It’s an advisory call where we’re guiding them through the process. People appreciate that. It’s part of the service.”

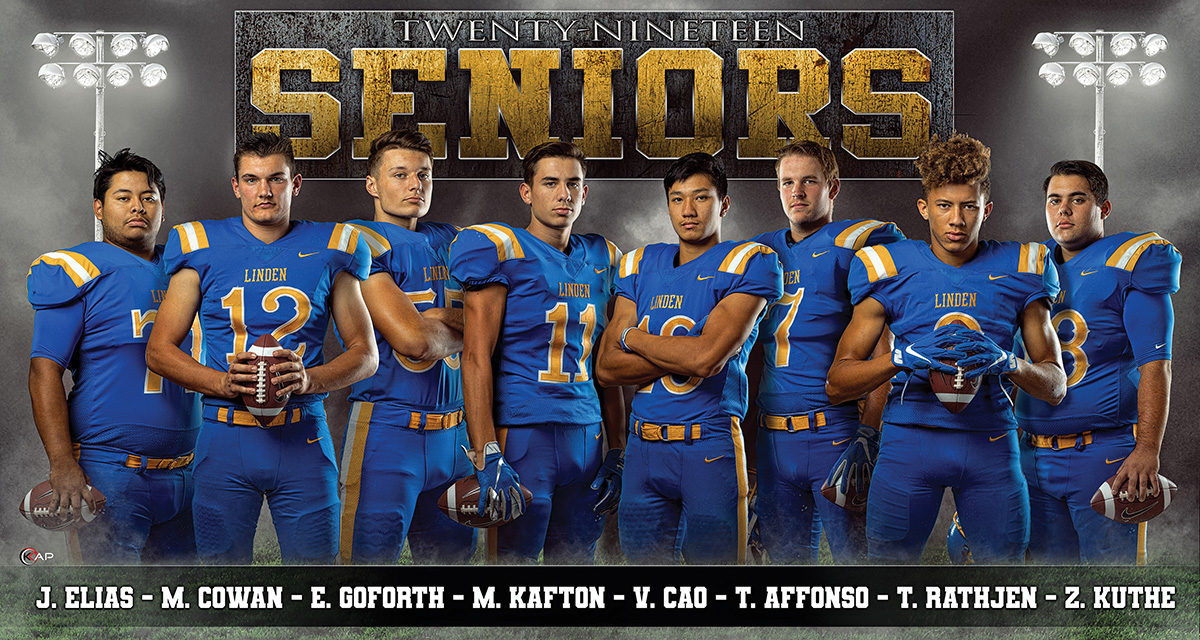

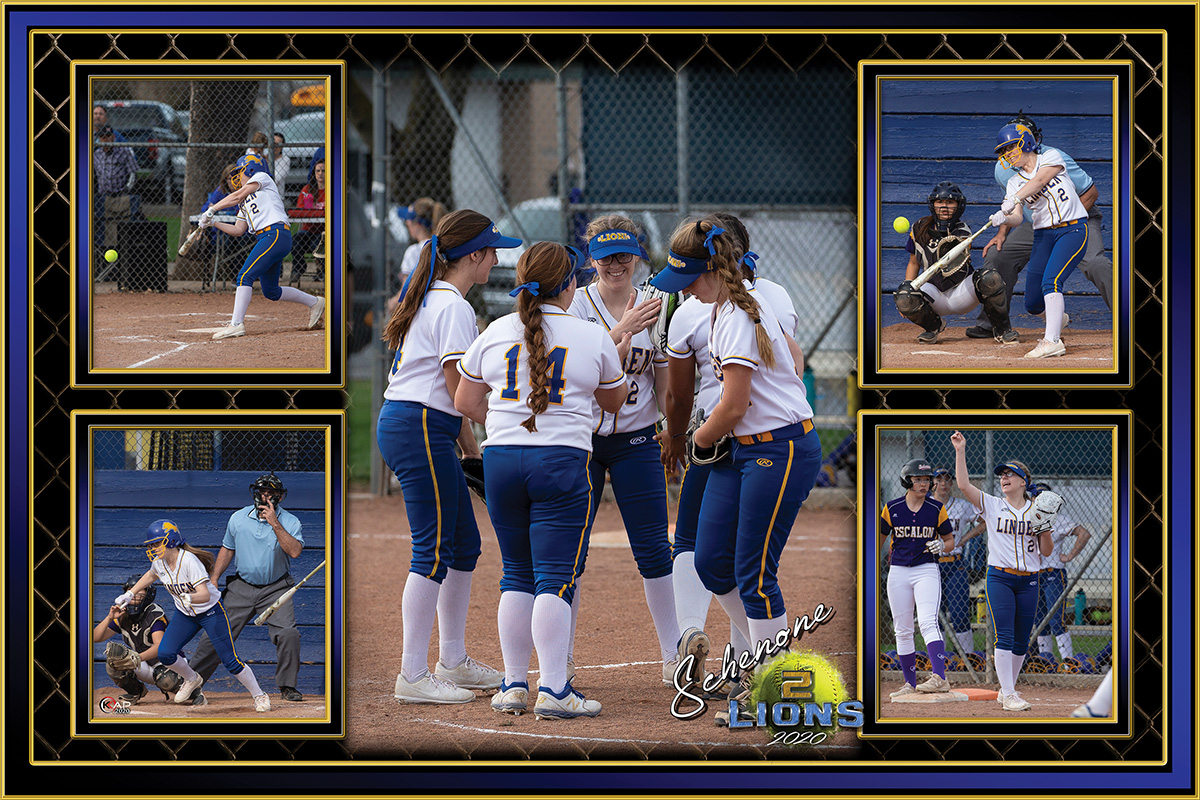

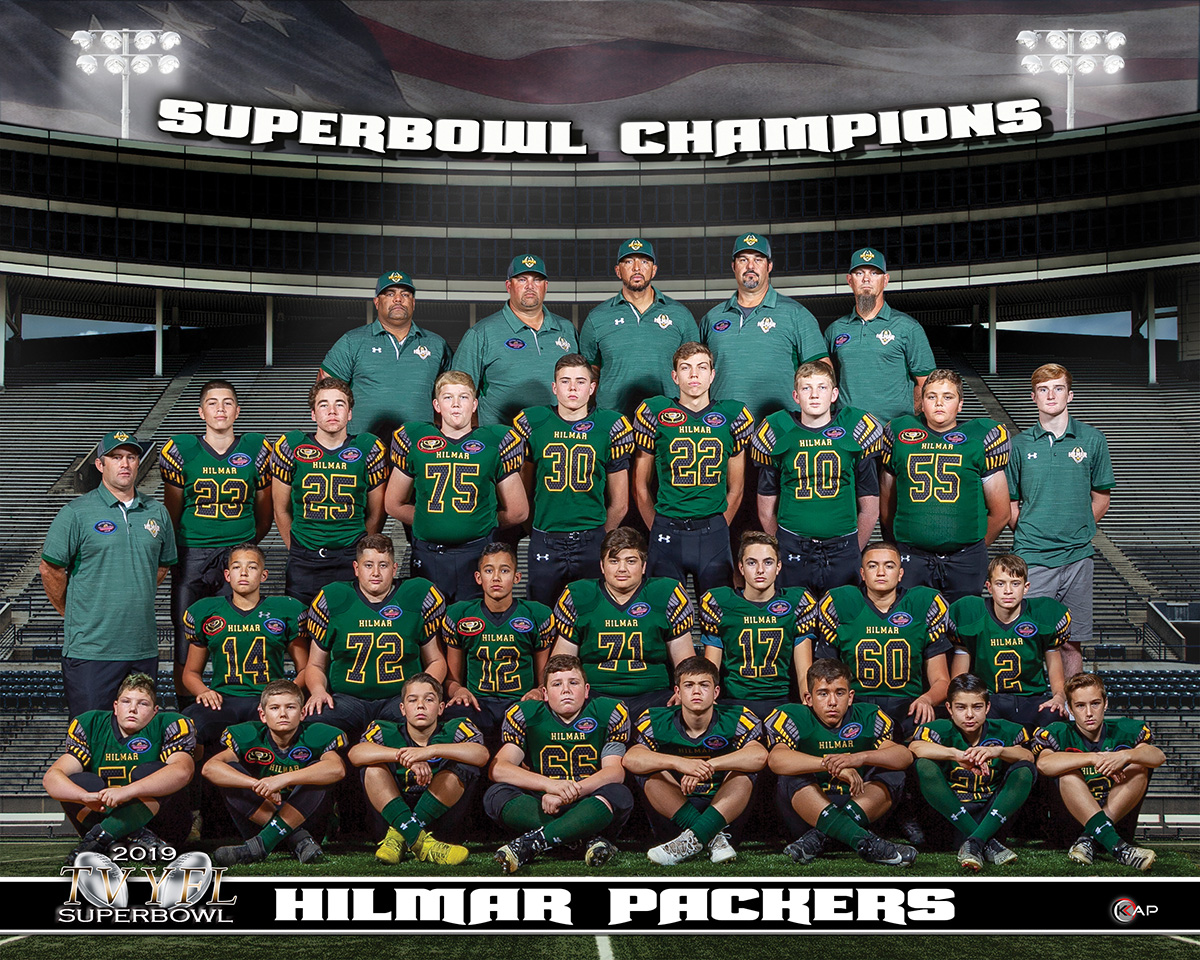

While on location, Brown displays what he wants to sell. His marquis product is a framed 20x30-inch collage. He displays multiple samples of these collages all around his tent. During the sales call, his team will ask, “Do you want the one you saw in the booth or the smaller one?” Almost everyone wants what they saw in the booth, which is a $150 upsell from the smaller option. Framing is an additional charge, and again, most parents opt for the add-on because it gets them exactly what they saw in the booth without any extra work.

If parents want to purchase additional images, Brown sells the remaining group of either print-quality digital images or, at a lower rate, web-quality files.

Presentation matters

“There may be other photographers out there at these events, and maybe some are even better photographers,” says Brown. “But it doesn’t matter because they don’t have a show like us.”

Brown’s team uses Canon gear and the big 400mm lenses used by photographers who shoot professional sports for major media outlets. His team members wear matching logoed uniforms. They communicate via radio and follow a carefully orchestrated plan that rarely lets anything slip through the cracks. The operation instills confidence in customers.

“I don’t care if there’s another photographer out there shooting for free or for less,” says Brown. “The amateur who’s giving away photos or selling them for cheap isn’t taking away from our market because those aren’t our customers anyway. We just need to focus on the people who appreciate what we provide.”

Getting started

The presentation is a nice differentiator, but Brown stresses that you don’t need all the bells and whistles to get started. “We bought all that extra gear from profits,” says Brown. “It’s not necessary in the beginning, though. All you really need is a good product, great service, and the ability to shoot sports well. Make sure you value yourself and charge for your time. Everything else will come from hard work and consistency.”

Jeff Kent is the editor-at-large of Professional Photographer.