It sounds like he’s underselling. “All I’m doing in photography is I am walking around the world with a rectangle,” says internationally acclaimed photographer Michael Eastman from his St. Louis, Missouri, studio (“in the middle of the middle of the country,” as he likes to say).

The bearded 74-year-old, who’s often told he’s a dead ringer for Jeff Bridges’ iconic “The Dude” character in the cult film “The Big Lebowski,” pauses a moment before continuing.

“A rectangle,” he repeats. “A frame.” Another pause, accompanied by a wide, Dude-like smile: “But there’s more to it than that. You have to know exactly where to put the camera; exactly how high or close or far away from the subject. It’s all about framing and what’s in that frame. It’s not enough to merely find a great place or scene or moment.

“Take Henri Cartier-Bresson, for example. He was famous for capturing the moment, but he was also a master at moving the camera—framing his shot—in a split second to get that scene. Ansel Adams famously said he could move entire mountain ranges miles simply by moving his camera a few inches.”

Eastman remembers photographing with a friend on a St. Louis street. “We would stop and shoot the same scene, and after we compared our images he’d invariably ask me, ‘Why is mine never as good as yours?’ I’d tell him that the difference between us is that I know exactly where to put the camera. I wasn’t being a smart ass. I’d explain that moving the camera an inch or two to the left or right or up or down makes all the difference in the power of a photograph. And I’m no genius; it’s taken me four decades to learn that, to get that right.”

Dialing Ansel

Eastman is largely self-taught. He counts among his early influences Eugène Atget, Walker Evans, and Edward Weston. “I devoured Weston’s ‘Daybooks’ and identified with his artistry,” remembers Eastman. “In fact, I’ve often said that if I had more patience, I would have been a painter. But I fell in love with the immediacy and democracy of photography.”

Eastman smiles as he remembers his younger self, whom he describes as “eager” and “not at all shy.” After borrowing a Nikon and printing his first photographs in a friend’s darkroom, he immediately rushed out to make business cards and boldly pronounced himself a photographer. “Some nerve, huh?” he remarks. He enjoys telling the story about the time he was having problems making some prints in the 1970s. “I was using Ansel Adams’ zone system but was troubled with mottling and uneven development. So I called 411 in California—remember this was 1973—and asked for Ansel Adams’ phone number. I got it, called him, and he answered. Really! He was happy to help. Can you imagine someone doing something like that today?”

After struggling to earn a living as a printer and a photographer, shooting headshots, family portraits, and other work for local clients—“We’re talking $5 an image for local publications”—Eastman worked on improving his craft and developing his composition skills. He eventually landed commercial work, such as shoe catalogs, but always made time to create his own personal fine art, using an 8x10 view camera on a tripod to make abstract and architectural images in St. Louis. “Back then the commercial photographers I met said I was wasting my time doing fine art work while the fine art people, mostly academics, told me I was corrupting my vision by doing commercial work. I’m glad I didn’t listen to either side because they were both wrong.”

“Back then the commercial photographers I met said I was wasting my time doing fine art work while the fine art people, mostly academics, told me I was corrupting my vision by doing commercial work. I’m glad I didn’t listen to either side because they were both wrong.”

Michael Eastman

The Feel of It

A steady stream of commercial work kept Eastman going, and in 1982 he had an aha moment that would change his life. “I’d been shooting exclusively in black-and-white, but as an experiment I took a picture of an art deco style window in St. Louis—an abstract—in both black-and-white and color,” says Eastman. “When I put the prints side by side the difference was amazing. There was so much more information in the color image compared to the black-and-white. It went from something that was cool and removed to something that was warmer and more emotive. There was lots of emotionality in the color. I never shot black-and-white again.”

As the years passed, Eastman got more and better paying editorial and commercial work for clients such as IBM, Life magazine, Time magazine (five covers), and The New York Times as well as prestigious advertising agencies such as Leo Burnett. “Those were the big money days,” he remembers. “And that was fun. On one assignment while shooting images for a Marlboro advertisement I actually got to bum a cigarette from the Marlboro Man.” But he never stopped shooting his personal work, which eventually resulted in books, including “Horses” (Knopf, 2003), “Vanishing America: The End of Main Street Diners, Drive-Ins, Donut Shops, and Other Everyday Monuments” (Rizzoli, 2008), and “Havana” (Prestel, 2011). His images have been purchased for collections by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, The Art Institute of Chicago, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, among others.

"In many of his pictures it appears that something is just about to happen or has just happened. The viewer is often left in this wonderful kind of limbo. All of his work is magical.”

Duane Reed

No matter the subject, from horses to abandoned interiors in crumbling Cuban residences to disappearing American towns, Eastman’s personal work exhibits certain trademarks: the painterly use of color, a strong narrative quality, and a soulfulness. As one observer noted, “There is an interesting relationship between reality and imagination in his photos, perhaps because he shows us not just how places look but how they feel.” In his introduction to Eastman’s book “Horses” the writer William Gass explains, “… here are horses as horses are meant to be, as well as horses as they firmly are.”

Says St. Louis gallery owner Duane Reed, “Michael is an artist, and there’s no mistaking his photographs for anyone else’s. He has that rare ability to capture that evidence of a moment in each picture. His images leave you with a feeling of everything from solitude to loneliness to mystery. In many of his pictures it appears that something is just about to happen or has just happened. The viewer is often left in this wonderful kind of limbo. All of his work is magical.”

Eastman admits, “I often look for places that have a sense of being inhabited. I am providing a stage or a set and I want the viewer to create his or her own narrative.” That’s one of the reasons he doesn’t include people in his photographs. “I see my interiors, including the architecture, the style of the furniture, the memorabilia, as portraits of those people who inhabit these spaces. I’m trying to capture a human presence without anyone in the frame.” Also, he rarely “tidies up” a scene. Rather, he typically leaves objects in these interiors exactly as he found them.

Cuba, which he first visited and photographed in 1999, had long intrigued him. He was attracted by its faded glory and the idea that it had been frozen in time. As he has said, “I am as much a historian as I am a photographer. Every photographer wants to go back in time to be their own version of Eugène Atget in Paris at the beginning of 20th century or Walker Evans in the American South during the 1930s. And except for Cuba, so many places have been renovated or torn down. It was the chance to photograph somewhere that hadn’t changed for 50 years that drew me there. It was an opportunity for time travel. And it didn’t disappoint.”

In 2010, when he returned to Havana for the fourth time, he was disappointed to find many of the residences he had visited had been renovated. One of his most-loved buildings had been gutted and turned into a hotel. “Much of the charm, warmth, and patina of those rooms were gone,” he says.

Always in Motion

Eastman still uses a large-format camera, a digital Phase One, to produce massive, 6x8-foot prints that, as he explains, “Include so much detail that a viewer feels he or she could literally enter the picture.” He regularly uses available light and long exposures (up to three to four minutes) instead of artificial lighting. He edits images in Photoshop, which he describes as “far more accurate than the old dodge-and-burn darkroom days.” His work is highly prized, with limited-edition Cuba and other large-size interior prints selling for $14,000 to $35,000.

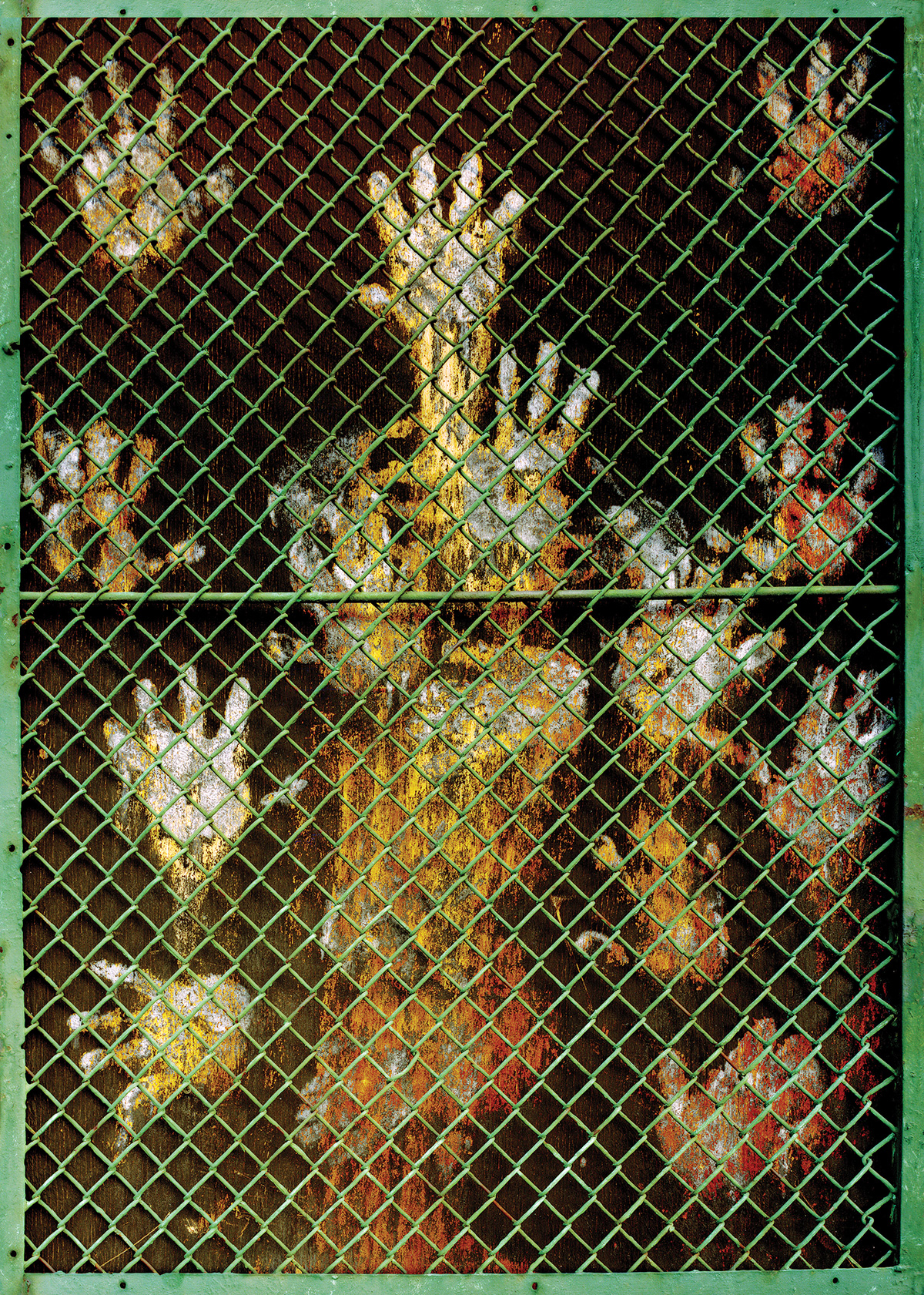

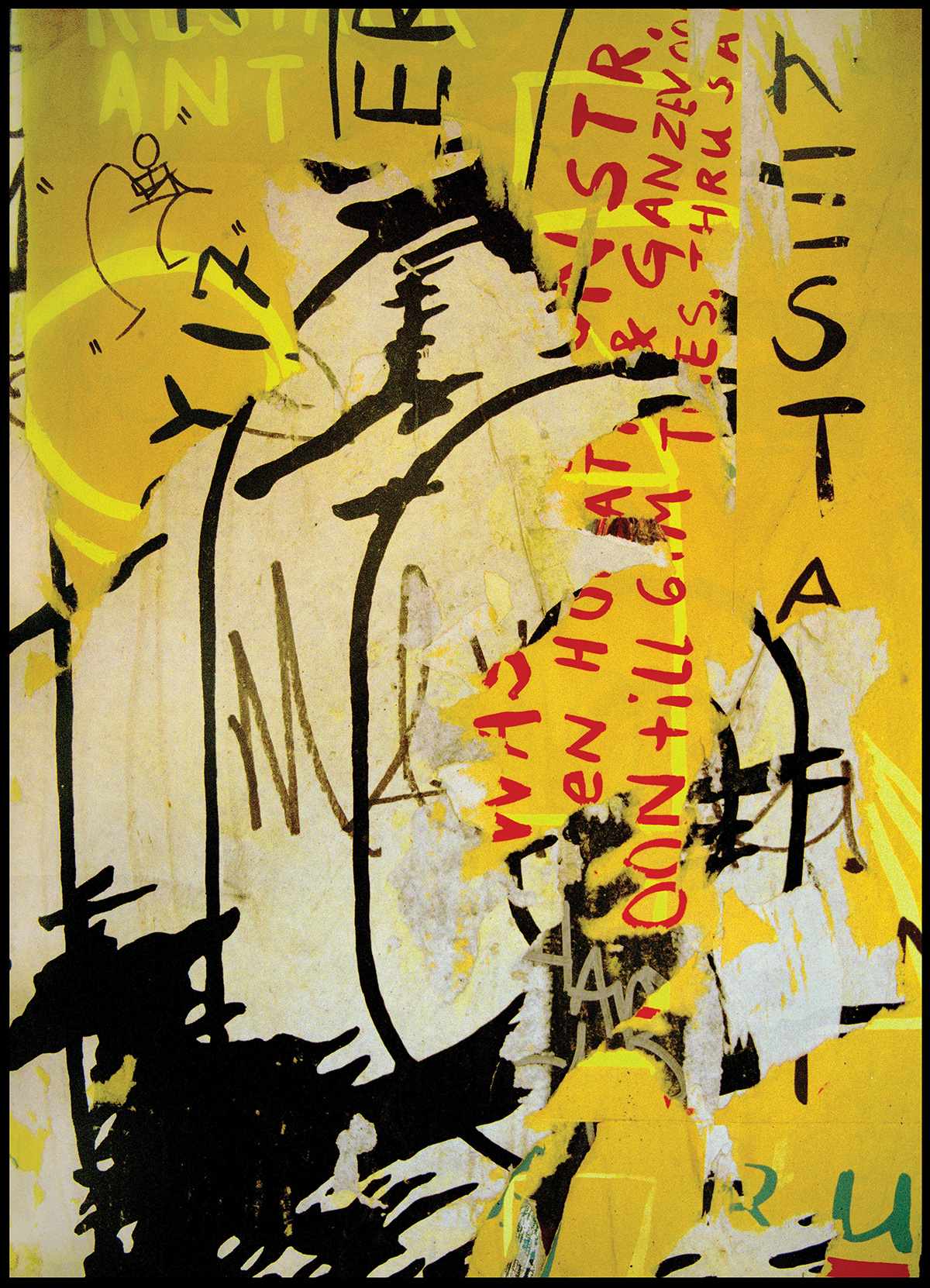

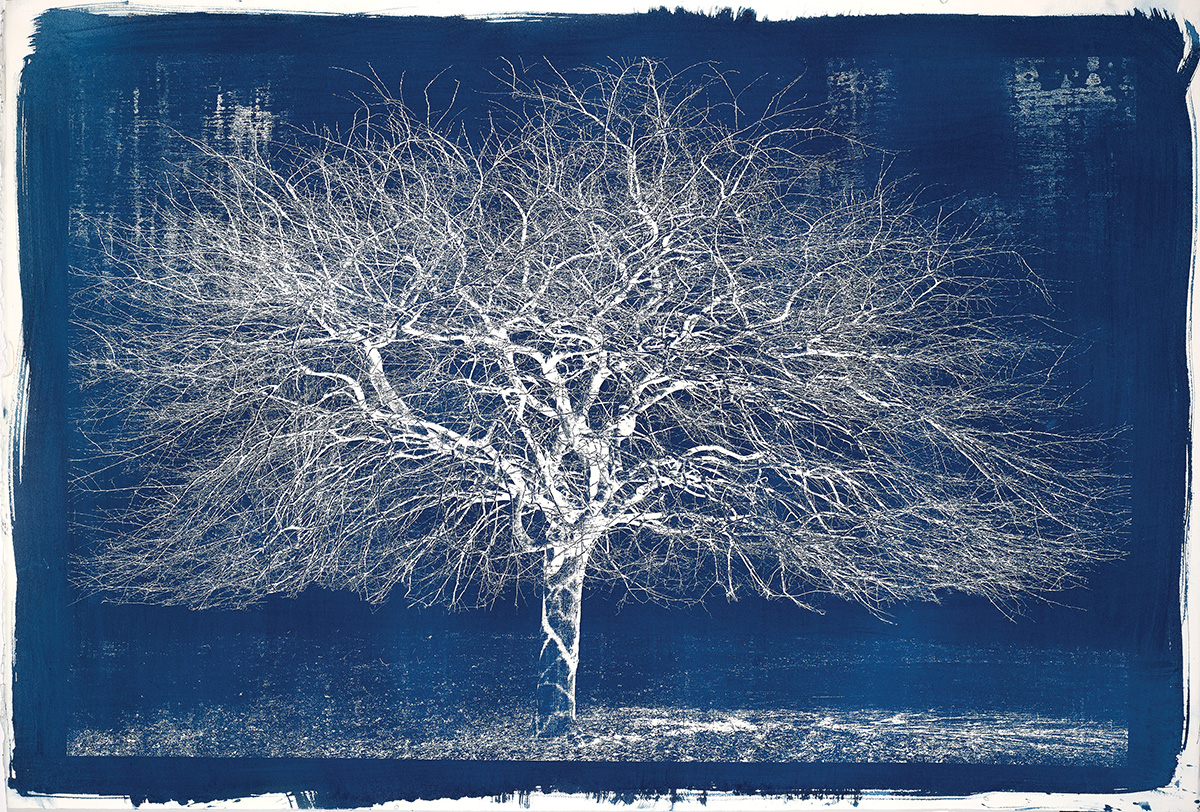

What’s next for this much-praised photographer who half a century ago called Ansel Adams for advice and now edits on a computer? “Michael never sits still,” explains Palm Beach gallery owner Holden Luntz. “He’s not an artist that repeats himself.” Eastman has produced a series of large-scale abstracts, “Urban Luminosity,” and created photo collages. His latest project is a return to photography’s roots: He’s experimenting with the age-old printing process of cyanotypes. “It’s interesting, I used to spend ages cleaning my negatives and making sure they were completely free from dust or spots. Now I’m just thrilled to see and welcome whatever turns up when I use this crude, centuriesold process,” says Eastman. “You know, I’ve been interested in alternative printing processes my entire life.”

As he looks over one of his recent blue-and-white cyanotype prints, he admits, “I don’t know where I’m heading, but I’m enjoying exploring, experimenting, and pushing the idea of what a photograph is. I have high self-expectations. Always have. Every morning I wake up and think my best work is still ahead of me. I like that!”

Robert Kiener is a writer in Vermont.

View Gallery

View Gallery